- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

“It’s a common fear among the women in the villages, that phone call with the person on the other end delivering the ominous message: ‘Your husband … it got him.’”

- Hasnain Kazim, Spiegel.

The Sundarbans, a vast expanse of marshy forest land with mangroves and mud-flats galore, sprawls across the south-west of Bangladesh as well as parts of India’s own West Bengal. As a National Park, Tiger Reserve and Biosphere Reserve in India, the wildlife here is ruled by a royal carnivore on the prowl, and as a result of climate change, these Bengal tigers have redirected their hunt.

Who are the tiger widows?

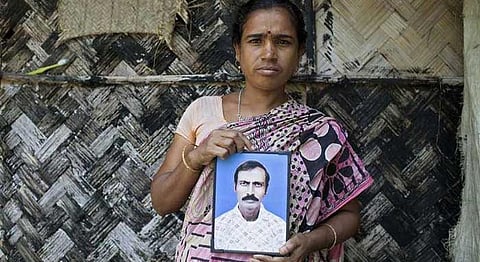

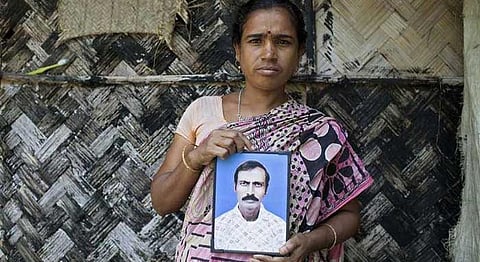

“Only widows would be left to live in the villages,” said Sheba Mridha, after her husband Ramesh Mridha was killed by a Royal Bengal on the creeks of Sundarbans Tiger Reserve while he was catching crab. While her statement might seem like one of exaggeration, prompting you to wonder how an entire village could be inhabited by only widows, she speaks of a grim but very serious reality--one that’s unique to this village.

A district known as Jharkhali, the village of Jelepara in Bangladesh, West Bengal’s villages of Jamespur, Bali and Annpur, and several other areas dotting this beautiful and equally dangerous rich mangrove forest have one thing in common--they’re all home to ‘Tiger Widows’. Having evolved after numerous attacks alike, this term is doled out for those women living in these areas who were widowed at the hands of Royal Bengals, either marking their territory or hunting for food.

The Status of the ‘Tiger in India\ 2014 report estimated an average of 74 tigers in the Sundarbans, while the Wildlife Institute of India (WWI) and World Wildlife Fund (WWF) put the number closer to one hundred. And while there’s a high enough number of reported tiger-attacks and tiger-human confrontations, the unreported cases add to that stack. “Many killings go unrecorded; often villagers don’t report attacks in restricted forest areas for fear of being fined or having their fishing permits cancelled,” stated Pradip Shukla, director of the Sundarbans Biosphere Reserve, as he refers to boating and other licenses provided by the Forest Department Officials, which many of the villagers don’t have.

Watch this BBC documentary of the Tiger Widows.

What do climate change and poverty have in common?

As Saba Naqvi writes in her book In Good Faith, “Much of the region comes under Project Tiger where human habitants are banned. But there are several villages on the edge of the waterways and forests where a mixed population of Hindus and Muslims struggle to eke out a living through subsistence-level farming, a very basic form of fishing where villagers stand submerged in water for hours with their nets, woodcutting and honey collecting.

The people are desperately poor and life in the delta is harsh.”

Fishing, crab-catching, honey-collected and wood-chopping, among others, are the bread and butter of these villagers. As essential as they are for survival, however, they are also what lures them to their death. Poverty forces them to venture further into the forests or take out their boats, putting them right in these tigers’ paths.

These week-long journeys are undertaken almost two or three times a month. And as these fatal attacks can be attributed to dangerous livelihood prospects at the hands of resource scarcity, climate change shares in the blame as well.

Accelerated rise in sea levels in the area has spurred an increase in salinity in the Southern Sundarbans, forcing the carnivores towards the villages in the north. As Professor Pranabes Sanyal of Jadavpur University in Calcutta elaborated on the tigers’ shrinking habitat, “That in turn is causing the migration of the tigers from the southern islands towards the north, close to the human habitation.

That’s why we have this man-animal confrontation - and the confrontation is increasing.” Additionally, during breeding season the tigers make their way to the islands for a safe-haven to keep their cubs, which draws them closer to these village communities. And to add to this peril, the Sundarbans are crawling with poachers and bandits that pose a whole new threat to these men working in the forests.

Ostracisation, impoverishment & The Tiger Widows Association

“I was 15 when my mother and father told me I was going to be married. I had a good marriage and a good life. I don’t miss my husband; I can survive by myself and take care of my son and daughter. Things are okay but sometimes I have to borrow money.

Things are not good, but okay,” said Ali Moti after her husband Nabo Kumar Mandol was the victim of a tiger attack in Bangladesh’s Sundarbans in 2011. While her words resonate those of strength, several other Tiger Widows in both India as well as Bangladesh aren’t as hopeful.

Numerous Tiger Widows are ostracised from society, and further impoverished with barely any source of income after their husbands, the providers, are killed. With these villages bereft of stability in terms of self-sufficiency, organisations such as the Tiger Widows Association as well as Christian Aid work in these areas focusing on women empowerment through self-help groups, and vocational training such as organic vegetable farming, animal husbandry and crafts. Along with non-profits providing aid to these villages, there’s one other place that they go to for solace.

Bonbibi worship, where Hindus and Muslims pray in fear alike

Under tiny thatched roofs, make-shift shrines adorn a tall clay figure of a woman with a painted face, and scores of men bow down to her in veneration before fishing, woodcutting, or honey collecting. And in hopes of their safe return, women of the villages revere the same deity.

The villages bordering the Sundarbans are mixed-religious communities, with both Hindus and Muslims residing in harmony.

And, uniquely, they have a common religious identity as well. Bonbibi, the Forest Deity, is believed to protect and strengthen her worshippers against the wrath of tigers as they venture into the marshy forests for their work.

As the rhythmic chants of “Maa Bonbibi Durga Durga” mingle and synchronise with those of “Maa Bonbibi Allah Allah”, Kanai Mondal, a honey collector from Bali Island’s Shaterkona village, further attested, “The forest and the tiger bind us together. A Muslim may pray five times in a mosque, and Hindus perform aarti in the temple, but when it is time to go into the forest we are all together in our prayers to Maa Bonbibi and her mount Raja Dakshinrai. A night in the forest is enough to teach you that.”

Connecticut College’s Assistant Professor of Religious Studies, Sufia Mendez Uddin, in her travels to the Sundarbans, attempted to understand and record the largely oral traditions and rituals surrounding this deity. And her learning marks a difference between the Hindu and Muslim worship of the same idol.

For Muslims, Bonbibi is a Sufi saint, a woman endowed with powers by God, and her protection is sought through red flags and flower garlands. On the other hand, for Hindus, she is a Goddess for whom worshippers leave offerings before the clay figure.

Uddin believes that this shared worship is a reflection of one simple thing: a shared dependence on the forest and a very practical need for protection.