Why Mumbai's Citizens Need To 'Learn To Live With Leopards' & Redefine Our Unique Ecosystem

India may be a real test for survival in a crowded world—and perhaps a model for it—because leopards live there in large numbers, outside protected areas, and in astonishing proximity to people.

Richard Conniff

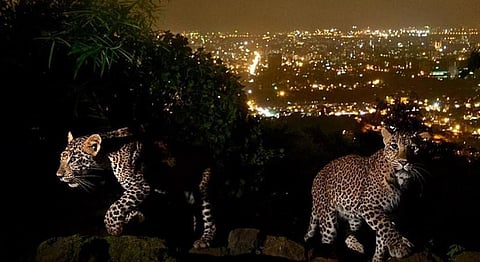

National Geographic’s Instagram account always tends to shake us out of our urban cocoon and smack us down right in the epicenter of a world where we’re forced to confront other species, eye to eye; and even man to leopard, in the case of the image below.

Richard Conniff traces the incredibly unique urban-jungle existence of this big cat and questions, particularly in the context of India, in a fantastic piece on National Geographic which begs the question–as humans encroach on their habitat and leopards are learning to adapt to these city-bound surroundings, can we humans do the same?

When you take the majority of headlines that tend to pop up around these glorious animals, the instinctive answer is probably not. In May of this year itself, a two-year-old named Sai Mandalik was picked up by a stalking cat, never to be seen again in the Junnar district, just 95 miles East of Mumbai, and that was the third attack and second fatality in the district in just two weeks.

But as tragic as a few such tales are, for the large part, it cannot be ignored that leopards and humans have been coexisting peacefully for the most part for many years now, and a lot of that has to do with the majestic cat’s shockingly prolific ability to adapt. So let’s take a look at its existence in Mumbai.

According to the National Geographic article, “About 35 leopards live in and around this park. That’s an average of less than two square miles of habitat apiece, for animals that can easily range ten miles in a day.

These leopards also live surrounded by some of the world’s most crowded urban neighborhoods, housing 52,000 people or more per square mile.” Another article in the Guardian suggests that there are over a million people living around the borders of this park, which only further suggests how badly we have encroached on their natural habitat.

Though this might seem like abysmal conditions to exist in for a jungle cat, these leopards have found a way to thrive. With a mixed diet of both what’s readily available in the park, like spotted deer, they also find their way onto the streets of the city, where they can find more supplements to their diet in the form of pigs, chickens, goats, rats and all the other such animals that tend to go hand-in-hand with human settlements.

Since they have been known to attack and eat humans too, however, there is a naturally growing fear around living next to these wild animals for many who live in areas like Borivali that surround the park, leading to an obvious conflict between the two species.

It was from this conflict that the project City Forest Initiative by 40-year-old Krishna Tiwari was born, in an effort to make citizens aware of how to live with their four-legged neighbors more safely and amicably.

In awe of the forests in Mumbai and Thane from a young age, he was always drawn to nature conservation, and considers the risk of leopard attack fatalities negligible, not to mention bitterly misunderstood.

When interviewed by WSJ, he stated, “It’s important to keep perspective. Leopards do kill humans when they are provoked, or when they mistake humans for other animals. But thousands of people die every year in road and rail accidents in Mumbai.

And if you compare this with people being killed by leopards, the risk is negligible. In fact, it is the leopards that are in danger. Heavy infrastructure growth and encroachment on nature has altered the habitats of these cats and depleted their prey base. This has threatened their future survival.”

Moreover, he brings to light an interesting juxtaposition between tribal communities and urban communities when it comes to co-existing with leopards. The former has been living with leopards in forested parts of SGNP and Aarey Milk colony for years, and even worship them as Gods.

Their attitude is largely tolerant towards them, and in stark contradiction, locals aren’t used to the animals which is they are at such high risk for attacks. As Tiwari puts it, “the leopards can sense their discomfort.”

Ultimately, it’s all about solutions. According to Tiwari, they’re not hugely complicated ones either. He recommends understanding the nature of the beast better, and realizing that a mere sighting is not cause for fear.

“Leopards are inherently cautious and will avoid a confrontation with human beings,” he says, adding that it is “unreasonable to expect a cat to understand man-made boundaries, they will only come if there’s food.” As such, it’s vital that we stop dumping our garbage out in the open, which further attracts smaller stray animals like pigs and dogs.

It also helps to ensure that the compound is devoid of other livestock. Additionally, understanding the cat’s habits better can help too. They’re more active in the dark, so night-time requires extra precaution and children shouldn’t be left unattended. Most importantly, cornering a leopard with a crowd is one of the worst ideas there is, yet something so many urban communities resort to. This only aggravates an animal that’s merely trying to escape.

As Conniff states in his article, “The two great leopard population centers, sub-Saharan Africa and the subcontinent of India, are among the most populous regions in the world.”

In India, SGNP is thought to have the highest concentration of big cats in the entire country. Taking all of this into account, alongside what we already know — that healthy predator populations are absolutely essential for a healthy ecosystem — we’re left in the challenging yet important position to lead the world in the matter of how to co-exist with these very predators.

If lions are the king of the jungle, then it’s time we acknowledged, here in Mumbai, that leopards may well be the king of the urban jungle. It’s also equally essential, then, that we figure out ways to allow them to keep their crown.

Read Richard Conniff’s full feature on this subject on National Geographic.

Feature Image Courtesy of Steve Winter