- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

“My mother recognizes Earthquake tremors instantly. Afterall she has seen two major ones,” Salim Dawood Khatri says, as he lays an exquisitely embroidered blue jacket in front of me. “Only 700 bucks, Madam,” he adds, persuasively. For a second I cannot take my eyes off it. Everything from the mirror work to its symmetrical design is perfect. “So were you personally affected....by the earthquake in 2001?” I ask, looking up at him. He doesn’t take more than a second to respond. “Obviously, all of us were. But we have moved past it now,” he says brushing his long henna-coloured beard. “Calamities are a part of our lives. Cyclones, earthquake, droughts, famines, we’ve seen them all,” he says simply, shrugging it off in favour of further jacket persuasion. I ask him to pack it for me and as I rummage through my purse to pay him, he suddenly adds almost as an after thought, “My brother lost his wife in the earthquake. Although my mother made everyone rush out of the house, my sister-in-law was a little slow. She was off. Our house in Dhamdka village collapsed too and it took 7-8 months for my business to revive. But fellow Kutchis were helpful. The NGO’s were supportive too.... Here you go, madam,” he says handing the jacket off to me once and for all.

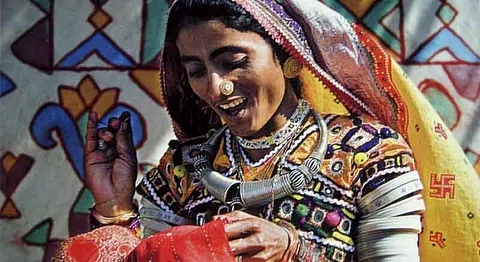

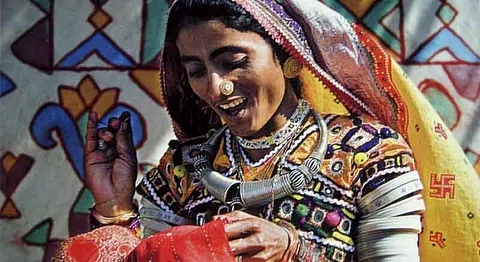

I have been in Kutch for less than 24 hours but I still feel very drawn towards it. The landscape is bleak, but the people, their houses, their attire is so opulent and vibrant, instilling colours and high spirits in a place that has seen so many adversities. The biggest one perhaps being the Bhuj Earthquake that reduced Kutch to a ground zero, hitting it with a magnitude of 7.7 on the Richter Scale, killing almost 20,000 people, injuring nearly 1,67,000 and destroying 4,00,000 homes. I am here, nearly 17 years after the unfortunate tragedy that still makes its presence felt subtly, talking to kaarigars ( handicraft makers) whose businesses were perhaps the worst affected.

Kutch is the largest district in India with 939 villages. It is also the only area that has it all: the sea, the hills, the grasslands and the white dessert. Each village in Kutch is home to a different community that practices its own form of embroidery and craft. What started out as a form of identity and self expression, was soon realized to have commercial benefits by many NGOs who worked in the area for craft revival and livelihood development. Many more Kaarigars started embroidering for commerical purposes after the earthquake. Today, Kaarigari is perhaps the biggest profession in Kutch with the entire family involved in handicraft making.

“My father migrated here from Sindh in Pakistan after the 1971 war. While we struggled with our own refugee crisis, we were hit by the earthquake,” says 35-year-old Sidhik from Nirmona village. A luhar (copper smith) who makes bells that come with a leather hanger, his stall is almost empty. “My father and I were outside the house working, when we first felt the tremors. My wife came running out too and we saw our beautiful house collapse into rubble within a matter of seconds. But I didn’t care about that. I was happy that my family was safe,” he says ringing a bell and interrupting my thoughts. I take the bell from his hand. It has a pink leather label, with green and yellow embroidery. My wife made that, he says proudly. “Are you still afraid of another earthqauke?’ I ask Sidhik, who is pleasantly surprised at someone taking so much interest in his life. “No, I am not afraid. But I am prepared.” he simply states. “Anyway, do you want this bell,” he asks. I politely nod.

The bell rings in my bag and constantly reminds me of Sidhik. I can only imagine his pain that he has built a wall against, just like he built his house entirely from scratch, this time using only mud. Most houses in Kutch are made of mud, with hay thatched conical roofs. The mud keeps their house warm in the winters and cool in the summers. “What’s the point of having concrete houses, when they are all going to collapse anyway. Kutch sees an earthquake every 50 years,” an elderly man tells me. “We are very rich. Our leather footwear is exported abroad too. But all these materialistic goods don’t last. We only believe in our work and in humanity,” he mutters, adjusting the red turban on his head. The tall old man is dressed in a long white kurta, adorned by a multi-coloured, heavily embroidered jacket and a plain white dhoti and is greeted by many people who pass by. I assume him to be a village senior, a man who could probably tell me how Kutch has survived and changed over the years. But he politely refuses to answer my question. “I am sorry, but I have too many customers to attend right now. Come to my village someday and I will show how Kutch thrives.”

There is a certain sincerity towards work and craftsmanship that I observe in the Kutchis. For them, their their craft is the ultimate salvation and they would continue doing it no matter what. Ami Shroff, Managing Trustee of Shrujan, an NGO that works for women empowerment and craft revival in Kutchi villages confirms the same. She tells me that post the 2001 earthquake, all NGO’s came together to form a federation or an Abhiyaan to carry out relief and rescue operations. “ There was so much solidarity among the Kutchis, post the earthquake. On the first two days, everyone was helping everyone. The teams were pulling people out of the rubble, and the rescued people were guiding us to the others who would be stuck in trouble. The third day when we visited them, they all sat on the debris, asking for work. I remember one particular weaver, who sat on his haunches outside his broken house saying, ‘if you have some work give it to me, else I will go crazy. Perhaps the most touching moment was when villagers asked me if the Shrujan Building was okay. They cared more about us, than themselves,” Ami says, visibly overwhelmed.

After the earthquake, Shrujan that was previously working with 3000 women in Kutch took a loan of Rs. 1 crore from the government and started working with about 5000 women. “It was during this time that women stopped making embroidery only for personal use but started doing it for commercial purposes. We literally pulled out embroidery archives, panels and other tools from the wreck so they could immediately start with their designs. The worst affected however were the Ajrak block printers, who lost their wooden blocks in the earthquake. “They had to start from scratch with minimum resources,” Ami explains.

The aftershocks of the earthquake were felt for almost 2 years and the Kutchis refused to sleep inside their houses. “We found families sleeping outside their houses in -2 degrees, when we went to distribute blankets. They seemed to have lost trust in their houses,”Ami tells me. It is a feeling that I observe continues even today. Kutchis seem to have no faith in money or materialistic goods. They know it is temporary and will wither away soon. What matters to them is the brotherhood and fraternity and most importantly their craft, so much so that most of them did not even accept donations. “Our craft is all that we have, all we own. It is enough to keep us happy in our little world.”Abdulgani Khatri, an Ajrak printer from Dhamadka village, says smiling. However the variety of handicrafts and textiles coming out of the little world of Kutch, have travelled far and wide into the masterpieces of big designers, fashion weeks and fancy labels. Most NGOs, design labels and the organisations working with Kaarigars in Kutch record massive turnovers.

That evening, I find myself in a bus to the Rann of Kutch, thinking about all my interactions with the kaarigars, when Nihaal Bhai, a team member at Shrujan and also our guide for the day reveals a shocking fact. Apparently Nihal Bhai had guided two American scientists who had visisted Kutch, post the 2001 earthquake for research and had revealed that if Kutch were to see another massive interplate earthquake, it might separate from the Indian mainland.

This riveting piece of information stays with me until I reach the great Rann, the magnificent white salt dessert that seems to merge with the sky, dissolving into nothingness. I sigh, thinking of how it was a perfect metaphor for Kutch. As I turn back, I see a few Kutchi women giggling and nonchalantly weaving an exquisite embroidery on a large piece of cloth. I am overwhelmed at their spirit and their dedication. I think of all the great lessons I will be taking back from this land. Kutch teaches you that nothing lasts forever. Except perhaps your spirit that should learn to smile and thrive, no matter what comes your way.

To ckeck out Shrujan and their work, click here.

Feature Image Courtesy: Amiya/Flickr

If you enjoyed reading this article, we suggest you read: