- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

The end of the British Raj in India in August 1947 left behind a violent legacy of Partition, the effects of which could be felt soon after. In an article for The Conversation, Sarah Ansari, Professor of History, Royal Holloway, says, “ ‘Partition’ – the division of British India into the two separate states of India and Pakistan on August 14-15, 1947 – was the ‘last-minute’ mechanism by which the British were able to secure agreement over how independence would take place.” The Partition triggered a wave of migration, with Muslims heading towards Pakistan and Hindus and Sikhs towards India, both hoping for a safe haven for their livelihood and survival. The mass migration eventually led to violent riots and casualties.

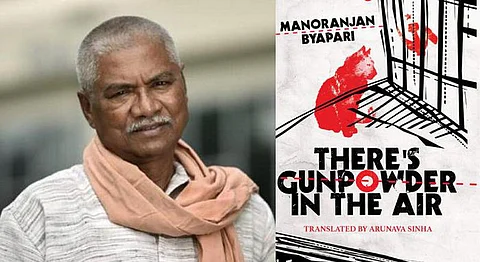

Upper-caste people who migrated to India after Partition were provided land, but Dalits were thrown into camps. Manoranjan Byapari, born in 1950 into a family of fisherfolk in the Barishal district of present-day Bangladesh was transported to one such refugee camp at Shiromonipur in Bankura along with his own family as well as 30 other families. In an article on Manoranjan Byapari, Sanghamitra Chakraborty writes for Reader’s Digest, “Memories of that terrifying journey—being bumped around in the vehicle in the searing heat, the air clouded with red dust from the tracks, a baby being born en route and an old man dying on the truck—were burnt into the brain of the 4-year-old.”

Since his days in the refugee camp, life has been a struggle for Manoranjan Byapari. He lived with his family in morbid conditions at the camp. Byapari recalls, “The rice we got had a disgusting sour smell and caused widespread dysentery.” He also recalls, “Every night, there were babies dying. It’s impossible to forget the loud wails of grieving mothers and the small pond close by, where dead babies were cremated. The fire never quite died down—the smoke from the pyre blew over the camp.” He himself was infected as an infant. However, when he was about to be buried the next morning, he started showing signs of life. Later, he was forced to move along with his family to Ghutiyari Sharif, Gholadoltala Refugee Camp, South 24 Parganas, where they lived till 1969.

Byapari left his home at the age of 14 and undertook a number of low-paid informal sector jobs in various cities in Assam, Lucknow, Delhi and Allahabad. During his teenage years, he was drawn to the egalitarian spirit of the Naxalite Movement which started as an armed peasant revolt in 1967 in the Naxalbari block of the Darjeeling district (West Bengal) and eventually gained a strong presence among the student movements in Calcutta. In order to take part in the Naxalite Movement, he went to Siliguri in North Bengal. However, when he returned to Kolkata in 1970, he was appalled by the death of a childhood friend (who was a CPM worker) in the hands of the Naxals. Feelings of disillusionment crept into him and he lost faith in the movement. Eventually, he got involved in the world of crime, hopping in and out of prison quite a few times. He also worked as a corpse burner in a crematorium, as a cook, a coolie and a rickshaw puller.

Interestingly, it was during his stay at the Alipore Special Jail in Calcutta that his life took a dramatic turn for him. He met a man of around 60 whom everyone called Mastermoshai (teacher), and who was lodged at the same prison wing as Byapari. Mastermoshai took a fancy to the young Byapari and tried to convince him to learn to read and write. Even though he did not care for it at first, he eventually gave in after much coaxing by Mastermoshai. He learnt to read and write in Bengali and was eventually exposed to the Bengali literary corpus through his Naxal friends, who lent him books. He was introduced to Maxim Gorky, Dostoevsky, Rabindranath, Sarat Chandra and The Red Book. However, what struck a chord with him were books by Mahasweta Devi and Chanakya Sen.

Here’s an anecdote about Byaparai’s encounter with Mahasweta Devi, in a way that could only be described as a tryst of destiny. Byapari recalls, “In the Pita Putra books, by Sen, I had tripped on the word jijibisha. I just could not find the meaning anywhere. One day, I had a passenger—looking at her I figured she could be a professor, as she had taken the rickshaw from Jyotish Roy College, and so might know what the word meant.” Since nobody till then could tell him the meaning of the word, he asked her what it meant, to which she said, “Jijibisha means the will to live. But where did you get this word?” A conversation ensued between the two, wherein both seemed curious to know everything about the other. Here’s an excerpt from the conversation between the two (published as an article in Scroll), from Bypari’s autobiography, Itibritte Chandal Jivan translated into English as Interrogating My Chandal Life: An Autobiography of a Dalit by Sipra Mukherjee.

So I asked her.

“Didi, if you don’t mind, can you tell me the meaning of jijibisha?”

She must have been surprised at the question. For she said:

“Jijibisha means the will to live. But where did you get this word?”

“In a book,” I answered.

A silence followed. There was no way I could see her face as she sat behind me on the passenger seat.

Then she asked, “How far have you studied?”

“I have not been able to go to any school.”

“Then how did you learn to read?”

“I learnt a little on my own,” I said.

The wheels turned and we moved closer to our destination.

But which wheels were really turning? The rickshaw wheels or the wheels of my destiny? Which moved forward? Was it just my rickshaw or was it me? Moving from a nameless life of darkness and humiliation to one of dignity and respect?

Then she said, “I publish a journal where working people like you write. Will you write for me? If you do, I will publish it.”

— Author: Manoranjan Byapari; Translated By: Sipra Mukherjee

On reaching her destination, the woman got down from the rickshaw, got out a pen and paper, scribbled some words onto it, and handed it to Byapari. She was none other than Mahasweta Devi, the Bengali writer and socio-political activist who has articulated the plight of the subaltern like no other.

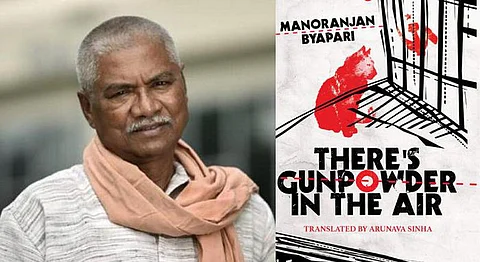

In the coming days, Byapari wrote his first article, Rickshaw Chalai (I am a Rickshaw Puller) under the tutelage of Mahasweta Devi, whom he had started visiting regularly by then. The article was published in Bartika magazine. He subsequently went on to write 16 books and numerous social and political essays. Arunava Sinha, translator of Byapari’s fictional account, Batashe Baruder Gondho says, “Byapari has an extraordinary empathy with everyone he saw struggling to survive, just like himself. He could have foregrounded his own unique experiences in all his fiction, but he chose instead to tell the stories of these other people, united in that they were all victims fighting back and refusing to surrender.” The book translated as There’s Gunpowder in the Air and published by Amazon Westland won the JCB Prize for Literature in 2019. It is a darkly comic critique of the Indian prison system as well as a deeply empathetic historical documentation of Naxalism in West Bengal. It is also an insight into what deprivation and isolation can do to human idealism.

Byapari’s autobiography, Itibritte Chandal Jiban won him the West Bengal Sahitya Akademi Award. His collection of short stories, Golpo Somogro (Collection of Stories), consists of several stories providing short accounts of his experiences as a goat- and cow-herd, teashop help, coolie, lorry helper, cremator of bodies, toilet cleaner, rickshaw puller and night guard - professions which are usually associated with the subaltern section of the society in India.

Today, Byapari lives with his wife and son, Manik, in Mukundapur in South Kolkata and is currently busy rebuilding his old home.

One of the most prominent Dalit writers of Bengal, Manoranjan Byapari was initiated into the profession as a reaction against the rise of Communism in Bengal which proved futile to addressing the Dalit cause. It is, therefore, more important to read the writings of authors like Manoranjan Byapari, Advaita Mallabarman, Harichand Thakur and others than those of Tagore, Satinath Bhaduri or Tarashankar Bandyopadhyay to gain an insight into Dalit life in post-Independence Bengal.

In a blog article, Debayudh Chatterjiee recounts an incident when Advaita Mallabarman, a Bengali Dalit writer having a Malo origin, while working on his seminal work, ‘Titas Ekti Nadir Naam’ (A River Called Titas) was discouraged by his friends who feared that Manik Bandopadhyay’s novel by the same name, Padma Nadir Majhi, would give him a tough competition. To this Mallabarman replied, “The son of a Brahmin has written from his point of view. I will write from mine.”

If you enjoyed reading this article, we suggest you also read: