- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

The article centres on Arundhati Roy’s decision to withdraw her film 'In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones' from the Berlin International Film Festival after jury president Wim Wenders suggested filmmakers should stay out of politics when asked about Palestine. It frames her withdrawal as consistent with her long history of political engagement. The piece revisits 'In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones' — a campus film set in 1970s Delhi about an architecture student whose impractical but community-oriented ideas clash with institutional bureaucracy.

The 76th Berlin International Film Festival opened on February 15, and at the jury press conference earlier that week, jury president Wim Wenders was asked about Gaza and whether filmmakers have a responsibility to speak when violence is unfolding in real time. Wenders responded by saying, “Yes, movies can change the world, not in a political way. No movie has really changed any politician’s idea,” and added that filmmakers should “stay out of politics,” arguing that once films are deliberately political, they move into politics itself. The comments quickly spread beyond the press room. Days later, Indian author and filmmaker Arundhati Roy withdrew her film 'In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones' from the festival’s Classics section, calling his remarks “jaw-dropping” and “unconscionable”, stating that she could not align herself with that position on genocide.

This isn’t the Wim Wenders we know. The beloved filmmaker emerged from the New German Cinema movement in the 1970s, a generation working through post-war identity in West Germany. His early road films — 'Alice in the Cities' and 'Kings of the Road' — followed men drifting through border towns and declining cinema halls at a time when the country was economically rebuilt but still marked by the aftermath of World War II and division. The films repeatedly return to men who struggle to connect, to communicate, or to situate themselves within a rapidly modernising society. Across them, Wenders captures a West Germany confronting its recent past while trying to define what its present identity looks like.

In 'Wings of Desire', we see Potsdamer Platz, a public square and traffic intersection in the centre of Berlin appearing as a barren strip of land because of the Wall that runs through it. Angels move across East and West side of the wall, listening to people think about the loneliness and trauma of this separation. The city is physically split and everyone inside it feels that split.

In 'Paris, Texas' Travis Henderson reappears after four years of disappearance, found wandering alone in the Texas desert near the Mexican border, and slowly begins trying to rebuild the family he walked away from. The film moves through motels, neon signs, empty highways, half-built suburbs in the American Southwest. This is the America of the early Reagan years, obsessed with reinvention and the mythology of freedom. The peep-show scene, where Travis speaks to Jane through a one-way mirror, lays out a marriage shaped by pride, money, expectation, and gender roles. Wim lingers on billboards and roads because those spaces say something about the country these characters belong to. In 'Buena Vista Social Club', he documents Cuban musicians whose careers had flourished before the revolution and faded from international view afterwards. They speak about the years when their music barely travelled beyond Havana. Their revival in the 1990s sits inside decades of political isolation. The film records that history in their faces and in their stories. You get the gist.

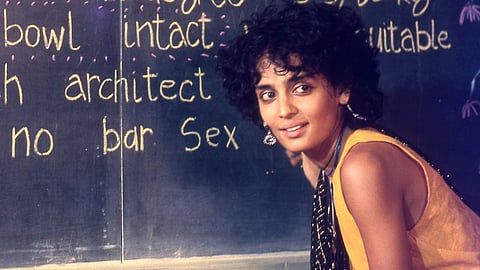

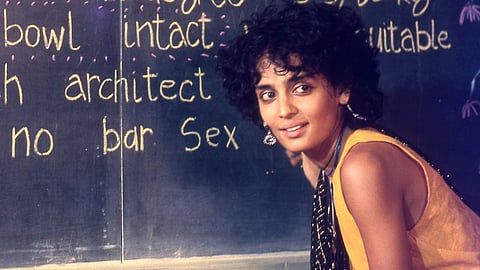

Given his own filmography, his statement about the political nature of films was a shock to everyone. Including Arundhati Roy who had been invited to present the restored version of In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones, the film she wrote and acted in, directed by Pradip Krishen, The film follows Annie, a final-year architecture student in 1970s Delhi, who keeps failing his thesis. He and his group of friends drift through campus life, skipping submissions, mocking professors, and constantly clashing with the administration. Annie’s big idea — planting fruit trees along railway tracks so passing trains can water them and nearby communities benefit — becomes a running thread in the film. It sounds impractical, but it reveals how he thinks about public space and development as a way to serve the community.

Under the comedy about hostel culture, procrastination, bad grades, and inside jokes is dissent. The film looks at educational institutions as bureaucratic structures that reward compliance. It touches upon class, state systems, and the limits placed on young people who want to think differently. Even in its humour, it’s rooted in a very specific India — one shaped by hierarchy, and the aftermath of the Emergency — and it captures that environment through everyday student life.

Even outside of cinema, as a writer and public intellectual, she has spent decades writing about nuclear nationalism, majoritarian politics, caste, displacement, militarisation, corporate power, the everyday consequences of state violence, as well as gender, patriarchy, religious fundamentalism, minority rights, and the criminalisation of dissent. Of course, she withdrew her film from the festival, that by the way, was founded in 1951 in West Berlin during the Cold War, backed by the American military administration, as a way to position West Berlin as a cultural and ideological counterpoint to the Soviet-controlled East, using cinema and international participation to project the image of a liberal, democratic society in a city that had become a frontline of global politics. The irony is staggering.

Film and politics have always been inseparable. Cinema emerged in the 19th century alongside industrialisation, factory labour, urban migration, and new technologies of mechanical reproduction; and was tied to modern industry, mass audiences, and the circulation of images at scale, (something thinkers like Walter Benjamin examined in the 1930s). Since then, every single movement that shaped film history grew directly out of its social and political climates: Italian Neorealism was filmed in the rubble of post-war Italy and focused on unemployment, poverty, and working-class survival; the French New Wave emerged amid youth rebellion and intellectual unrest in late 1950s France; Brazil’s Cinema Novo responded to class inequality and political instability; the Yugoslav Black Wave challenged official state narratives in socialist Eastern Europe. In India, Parallel Cinema in the 1970s and 80s — with directors like Shyam Benegal, Govind Nihalani, Mrinal Sen, and Mani Kaul — examined caste, labour struggles, agrarian distress, and state institutions during a period marked by economic shifts and the Emergency. But none of this is news to anyone in the film industry.

After Wim Wender’s comment, Berlin Film Festival director Tricia Tuttle came in to defend him by saying the festival is being weakened by “gotcha moments”, suggesting that journalists pushing artists on political questions creates a hostile environment and that filmmakers shouldn’t be cornered into statements. But calling it a gotcha moment makes it sound like someone tried to trick them, when the question was fair: why had the Berlinale shown solidarity with Ukraine and Iran in the past but not taken a similar position on Palestine? Plenty of artists like Mark Ruffalo have relentlessly spoken against the attack on Gaza as not a geopolitical but a human rights problem. There is nothing controversial or complicated about it. Avoiding that question or politics in general, then, isn’t a neutral position. It either signals an indifference that can only come from privilege because the crisis doesn’t affect you directly, or it is a way to hide the cowardice or guilt that comes from standing on the wrong side of history. Arundhati Roy chose to oppose that stance by stepping away from the festival precisely because she understands what complacency and inaction mean in a moment as crucial as this.

Follow Arundhati here and watch her film below:

If you enjoyed reading this, here's more from Homegrown:

The Death Of Creative Autonomy?: Raanjhanaa's New AI-Led Ending Is An Early Warning Sign

What Jaspal Bhatti’s Flop Show Says About India’s Lost Culture Of Public Criticism

The Angry Young Men Are Back, But India's Favourite Anti-Heroes Have Changed