- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

A slightly seedy Chinese restaurant in Andheri east is not where I imagined having a conversation with Sagar Abraham-Gonsalves. But, here we are, on a late Tuesday evening, sharing a bowl of Machow soup and conversation veering towards his relationship with his father, Vernon Gonsalves. Vernon was arrested on August 28, 2018, by the Pune police under the draconian Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act and the Indian Penal Code’s Section 153 (A) detailing criminal conspiracy and inciting violence between groups. Along with him, four other prominent activists and lawyers, Sudha Bharadwaj, Varavara Rao, Gautam Navalakha, and Arun Ferreira were also arrested under similar charges.

On August 29, in a hopeful judgement, the Supreme Court stayed the Pune police’s action of wanting to take all five activists into immediate custody saying, “Dissent is the safety valve of democracy,” and ordering the accused to be kept under house arrest till September 6, 2018. However, yesterday, on September 6, the Supreme Court ruled that house arrest will be extended to September 12, 2018 – the best case scenario for the arrested activists who could alternatively be in police custody.

One might expect Sagar to be hesitant about saying too much, partly out of fear of history repeating itself: this is neither Vernon Gonsalves’ first run-in with authorities nor the first instance he’s been staring potential jail-time in the eye. A social activist and former university professor, Vernon was accused of being a Maoist central committee member and arrested over a decade ago in 2007. After he was charged in 20 cases and spent six years in jail, he was acquitted in 19 of them, pending appeal in one in the Bombay High Court, and immediately released in 2013.

Now, in 2018, Vernon has been accused of being involved with Naxalites and received heat for his article in Daily O, “Why the letter about a ‘Rajiv-Gandhi-type’ assassination plot to kill Modi is fake,” which spoke about how the plot was conceived as a tactic to distract the public from the Bhima-Koregaon incident in June this year.

Of course, Sagar’s historical depiction of his father is another thing entirely. Despite the trauma of seeing Vernon taken away in handcuffs at the young age of 12, Sagar speaks admirably about his parent who is also clearly a role model. While telling me about Vernon’s life in Chandrapur between 1984 and 1994 where Vernon and his partner, Susan Abraham, an accomplished social worker and lawyer, did most of their work, Sagar says, “I was really struck by the impact my parents had had because every person they met was genuinely happy to see them.”

The more I hear about their awe-inspiring social work, the more I want a glimpse of his life at home because I’m curious about how this family manages to balance domesticity, professionalism, and danger. To this, Sagar says his mother is a pillar of strength, that she’s never faltered or shown a weakness that would translate into worry for him. “Especially when my dad was in prison for 6 years, I could’ve really spiralled. But, she was very strong… She’s a whole package,” he says, swelling with pride, of Susan.

Then, I ask about the first time Vernon went to prison, when Sagar was only 12 years old.

“August 18, 2007,” he recites as if the date was permanently tattooed on his consciousness. Sagar tells me of what he thought then was an uneventful Sunday night spent with his textbooks, waiting patiently for his father to return after going out to buy groceries. “I was studying till 12 o’clock at night, and that’s when they showed up… the cops,” he says. “This part is really burned in my memory… My father said, ‘I’ve been picked up’ and I saw handcuffs around his wrists,” Sagar narrates, looking down at his own arms and tracing where he saw his father’s restraints.

At midnight, over a decade ago, members of the Anti-Terrorist Squad conducted their first raid of the Gonsalves residence: Susan’s phone and the house landline were confiscated, CD collections and books were rifled through, and their home was turned upside down for six long hours. “I hadn’t cried about the whole thing during those six hours. But the next morning when father left, I broke down and told my mom to get him back soon,” Sagar admits while expressing fear and worry for his father’s well-being.

For a brief moment, the air between us is heavy and undisturbed for the first time since we sat down. Neither of us sips our soup; only I look at Sagar’s furrowed forehead concealed under his head of curls while he looks at the back of my laptop, both of us unsure about what to say next. I break the silence and ask about the impact of imprisonment on their father-son relationship and am pleasantly surprised by his response. “The issue was that my dad was very smart and would help me with studies, especially math… I was not good at math but I was really proud that didn’t go to tuitions… But, then he got arrested,” says Sagar, breaking into a chuckle that I happily join him in. Sagar says that his favourite thing about his father is his sense of humour and ability to find light in the toughest of situations. I smile to myself and wonder if he knows that the virtue he admires most about his father lives quietly in him as well, like a prized family heirloom.

“August is clearly not a good month for us,” Sagar penned on Facebook along with vocalising the helplessness that has been gnawing at him from within for the past week. “Back then it was the midnight knock now it was the morning bell. And believe me, it is not a good feeling. To be persecuted by the very state whose duty it is to protect and safeguard your rights,” he eloquently wrote in his post.

Sagar voices similar opinions to me this Tuesday night. Although he has never asked his father about life in prison, he says he might understand it a little now. At least six constables surround his residence 24x7, barely five steps away from his hall window. When I ask if he feels suffocated and trapped, he says, “I feel like I’m being watched constantly,” and made a gesture with his hands that looked like a strong spotlight shining on his face. I admit that if I was in his position, I would probably not feel safe around the authorities that conducted the raid in the first place. Sagar counters with the fact that his parents’ resilience is a strong source of support and reassurance for him. He adds that Vernon and Susan’s efforts to maintain normalcy at home and function as usual also helps.

But, do you ever feel scared, I ask. “No, I see them [parents] functioning and all... but, I don’t know, yeah a bit. I should be... The cops know me now,” he says gravely and rubs his forehead in thought.

On the Indian judiciary, Sagar says that the justice system works at too glacial a pace. Referring to his father’s six-year imprisonment, he says, “The process becomes a punishment. You’ve already become so persecuted, that that’s enough. The actual verdict doesn’t even matter.” I ask if he trusts the justice system to do its job; and Sagar graciously replies, “I have nothing personal against them. But, there are loopholes in the system. Ours is not the best judiciary.”

I wonder if he thinks anything has changed in the decade since his father’s last tango with the government, if there is anything about the recent outcry on social media that is working to his father and the other activists’ benefit. Sagar indulges my curiosity and responds, “A part of me wants to be optimistic about this [situation] because of all the support that’s come out. But, because of the way it got dragged the last time around, I’m aware of the way they [the cops] can really stretch this out. They have the resources for it.”

His concerns aren’t unique to his case. The ordinary Indian citizen hardly has the means for quality representation, whether that includes affording a good lawyer or having knowledge about their rights. Even if they do, the legal process is wrapped generously in red tape that does little for those eventually proved innocent who have lost precious quality time with their friends and family.

Sagar goes on to tell me about the virtual hatred his Facebook post received. “I hit a really bad low last night, reading what people were saying about me, my father, my family,” he says in a flicker of rage and frustration I see for the first time in the two long hours we have been spending together. He tells me about being hurt and frustrated after reading rude tweets and crass Facebook comments hurling accusations of anti-nationalism and other divisive language alluding to Naxalite and Maoist ideologies. When I ask if he thinks his parents are patriotic, Sagar says with utmost confidence, “They’re a hundred times more patriotic than the guys who have been saying stuff behind their keyboards… Calling someone else anti-national on the internet, doesn’t make you more of a patriot or nationalist… My parents have gone above and beyond for their country, they don’t deserve to go through this.”

I find myself sympathising with the 24-year-old man sitting in front of me as he relives the emotional trauma he experienced as a 12-year-old boy.

As Sagar tries to put into words the feelings of powerlessness, vulnerability, and injustice that he and his parents have been forced to navigate, I feel worlds apart from him. Many of us do not know this kind of struggle: to be a loved one of an individual or to love an individual constantly at odds with state institutions. But, hearing Sagar talk about his father humanised Vernon and personalised a situation that most of us may hopefully never experience.

TV news circus-like debates, sensational sound bytes, and jargon-filled text do little to help us understand what life might be like for the Gonsalveses of India. In the divisiveness of Indian politics and chaos of choosing sides, we often forget that real lives hang in the balance, lives with friends and family who are also forced to shoulder the emotional baggage and struggle that comes with punishments by a media trail that are more often the norm than the exception.

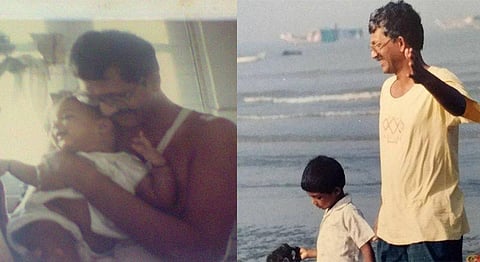

Feature image courtesy of Sagar Abraham-Gonsalves.

If you enjoyed reading this, we suggest reading: