- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

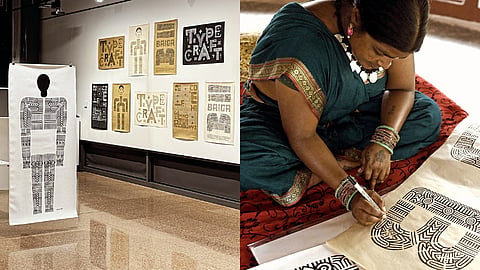

The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) has acquired a typeface derived from the tattoo traditions of the Baiga community in Chhattisgarh. At first glance, a font might seem an unlikely candidate for a permanent museum collection. Yet the Baiga Tattoo Typeface, developed through The Typecraft Initiative led by designer Ishan Khosla, is far more than a digital artefact. It's at once a preservation project, an act of collaboration, and a reimagining of how indigenous visual cultures might survive in a world dominated by screens.

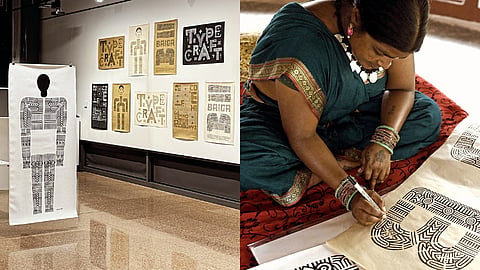

The works acquired by SFMOMA also include original drawings by tattooists Mangala Bai and Jumni Bai Maravi, screen-printed posters, animations, and a short film that documents the process. These objects record the process of 'Godna', the Baiga tattoo tradition.

Much of what is known of Baiga tattoos comes from the Badnin, the women tattooists of the Badi community. For centuries, they travelled from village to village, inscribing bodies with motifs that carried communal significance. A hearth tattooed on the forehead signified entry into the community; concentric circles across the chest marked fertility and identity; motifs of fish traps, ploughshares, or lamps encoded survival tools and myths.

Today, these women stand at the edge of erasure. Economic hardship, urban migration, and the stigma attached to hereditary caste practices mean that few young people want to carry tattoos forward. The knowledge that once passed from mother to daughter now survives precariously in the hands of a dwindling few. By transforming these motifs into typefaces, Khosla and his collaborators have created an accessible record of graphic systems that might otherwise disappear.

One of the most striking aspects of the project is the way it reframes tattoos as proto-writing. Anthropologists have long suggested that human mark-making — on caves, on bodies, on tools — predates and informs the birth of language. In the Baiga motifs, this continuity is palpable: dots for grains, chevrons for fish bones, circles for lamps and eyes.

The digital typeface carries this logic into twenty-first century media. Type a word like “plough” or “farming” and the script morphs into the corresponding tattoo icon. It underlines that we must see language as image and images as a living script.

The acquisition by SFMOMA raises an important question: what does it mean for an indigenous practice to survive via translation and to find its way into contemporary art circuits? There is always the risk of freezing a living practice into an artefact; of detaching it from the communities for whom it was never 'art' but a regular part of life. Khosla himself acknowledges this tension, and has affirmed that Typecraft’s model deliberately resists a top-down approach.

The Baiga project reopens debates about the politics of design education, the dominance of Eurocentric aesthetics, and the ways in which globalisation has stripped communities of their own visual languages. When Typecraft was founded in 2011, it emerged as a critique of an Indian design industry that had largely abandoned vernacular forms in favour of Western templates. By creating fonts rooted in tattoo, embroidery, weaving, and other community-based practices, the initiative insists that design is always entangled with history.

Whether the typeface becomes widely used or remains a symbolic gesture, its presence at SFMOMA ensures that Baiga godna won't vanish as its last practicing tattoo artists grow old. Baiga tattoos themselves contiue remind us that the act of marking — the desire to inscribe meaning on the world — is among the oldest and most enduring human impulses.

If you enjoyed reading this, here's more from Homegrown:

Indian Feature Films Exploring Female Desire & Sexuality In Realistic Ways