- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

When It Comes To Adivasi Women, Governments And Maoists Fail Spectacularly

The Vastly Under-Reported Sexual Violence In Maoist Conflict Zones

Forget Maoists, There Is A Deep Anti-Women Insurgency In The Adivasi Areas We Need To Tackle

The Deep Anti-Women Insurgency In Maoist Conflict Zones That Nobody Is Talking About

“Nobody’s right, if everybody’s wrong.”- Buffalo Springfield

Society’s exercise of dominion over the womb and fertility of a woman is as ancient an affliction as it is a moden one. The firm belief in the protection of a woman’s sanctity and hitherto the community’s reputation has seen women and children being made pawns in war as long as man has existed. Genghis Khan once even famously declared “The greatest pleasure in life is to defeat your enemies, to chase them before you, to rob them of their wealth, to see those dear to them bathed in tears, to ride their horses, and to ravage their wives and daughters.” The penchant for rape and multiple wives enjoyed by this ruthless ruler has now lead to the prediction that 1 in 200 males in the world share a Y Chromosome which is said to have originated from (the real) King Khan himself. Unfortunately, there seems to be no learning from humankind’s own history as sexual violence in conflict zones in both India and hundreds of other countries ravages on unchecked every day, even in the age of information. Or perhaps the stories just aren’t being heard?

Sexual violence in conflict cannot be simply dismissed as an antiquated and barbaric custom of the few. Not with horrific stories like ‘Rape of Nanking’ by the Japanese soldiers preceding World War Two being a part of the modern consciousness. “They stripped a girl naked…she looked scared and lost…three of them held her down. The soldiers told me I should rape her and the others too…“ recounted a soldier during the Bosnia-Herzegovina conflict of the 90s . A similar narrative exists in Darfur, Colombia, India and scores of conflict-ridden countries where sexual violence is seen as a means of ethnic cleansing and exertion of power on a community.

Did the mention of India perturb and startle you? It shouldn’t. India’s current gendered climate is a powerful one. Yet even as the issue of rape has burst through mainstream conversation, the depth of that conversation leaves a lot to be desired as is evident from the muffling of Sunitha Krishnan’s #ShameTheRapist Campaign, or the inability to move past the sensationalism of higher profile and ‘more brutal’ rape cases. More importantly, the issue of rape seems to be being stratified by socio-economic diktats much like everything else. As a result, ‘urban’ and more ‘upwardly mobile’ survivors tend to receive more coverage than others. And it’s in this light that the conversation about rapes in India’s conflict zones, specifically Adivasi women, becomes particularly pertinent.

The Maoist insurgency in general is one which the urban Indian finds relief in being oblivious and ignorant to. The occasional headlines grabbing act of attacks by the insurgents are looked at with baffling condemnation while reports of the security forces thwarting the plans of insurgents is lauded and celebrated with too little introspection or interest into the reasons for this insurgency and the conduct of the parties involved.

Hundreds Of Kawasis - THE WHOLE OF KAWASI’S STORY NEEDS TO BE CONDENSED A LITTLE. MENTION THAT IT WAS ARUN FERREIRA’S BLOG POST THAT ALERTED US TO IT AND USE IT AS AN EXAMPLE TO ILLUSTRATE THE LARGER PICTURE. BECAUSE RIGHT NOW IT SEEMS LIKE A STORY WITHIN THE STORY.

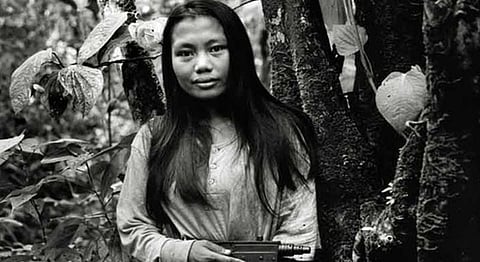

Sixteen-year-old Kawasi Hidme is one such story more people should be aware of. Nestled in these troubled lands in the Borguda village of Sukma District in Chhatisgarh, having lost both her parents, she lived with her aunt whom she helped till a small piece of land and survived on the rice grown on the fields as well as the sale of mahua flowers which helped her them by essential amenities. In January 2008, Hidme, her aunt and sisters went to a fair in the village of Ramram. Hidme danced with fellow youngsters and feeling thirsty, headed for a hand pump nearby. But as she was about to draw the water, she was forcefully stopped by a police officer. A team of police officers surrounded Kawasi and dragged her out of the fair. They tied her hands and feet as they forced her onto the floor of a truck and thus began her seven-year-long ordeal.

The truck stopped at a police station where she was kept and tortured for days until the police officers of one station were satisfied with her, after which she was transferred to another police station and another. The physical and possibly sexual torture took a severe toll on her health and the police officers panicked that she would die in their custody. A common practice with Adivasi women in Chattisgarh, women are kept in detention at police stations without any warrants or formal arrests. The police decided to have her transferred to jail but this required her to be produced in court—something her fragile health condition couldn’t permit. She was admitted to a government hospital after which she was produced before the court where she was charged with working with Maoists in the killing of 30 CRPF officials near Errabore Village in Bastar District on July 2007.

When in jail, Hidme’s health deteriorated as her body suddenly ejected her uterus. The scared Hidme, unable to speak Hindi and seek help, managed to insert the organ back in her body. She kept bleeding profusely and when the organ was about to eject once again, Hidme decided to take things in her own hands. She asked an inmate for a blade and when all the women had left the barracks, she attempted to remove the uterus from her body. But a girl entered the barracks and screamed on seeing the bleeding Hidme just before Hidme could perform surgery on herself. She was rushed to a government hospital where she was operated upon and resulting in nine stitches after which she was sent back to jail.

Meanwhile, the weak case constructed by the police against Hidme started to unravel with its weakness. Two women and two policemen were named as witnesses in Hidme’s case but the women were never presented before the court. The policemen refused to have any information about Hidme being involved in any nefarious activities. Soni Sori, a fellow inmate of Hidme, was granted bail and took it upon herself to secure justice for Hidme. Alongwith a few human rights activists and lawyers in the region, she sought the release of Hidme. When they appealed the judge for release since all the witnesses had been heard, the judge argued that since she had already spent seven years in jail, a few months more shouldn’t make a difference.

On March 28th,2015, Hidme was released after none of the charges against her could be proved. “I was never involved in any Maoist activity… What was my fault?” asked Hidme as the 24-year-old woman now attempts to piece back her life when even people from her village fail to recognise her after her multiple gallstone operations.

If you are wondering how this story didn’t receive an iota of national concern or outrage, the issue is compounded by an inadequate reporting of Naxalite violence. The story of Kawasi gained traction when a blog by Arun Ferreira narrated her incident, supported by a Hindi blog titled ‘Dantewada Vani’. The details of this case remain sketchy with the blogs not mentioning the word rape and the national reportage taking a cautious and sceptical view of Hidme’s claims. A Hindustan Times article quotes Hidme saying that she was applying Mehendi on the palm of her younger sister when she was arrested, disputing the claims made in the blogs previously, while describing her ordeal cautiously with “severe sexual torture to which she has possibly been subjected”.

In fact, this is what can be broadly said about reportage of sexual violence in Maoist conflict where a series of voices and personal blogs narrate incidents which the mainstream media treads lightly in reporting or is perhaps not privy to. A reproduction of a New Indian Express article, talks about how on 21st September, 2007, a group of Adivasi women in Vakapalli, Andhra Pradesh declared that they had been raped by 21 Greyhounds police in a memorandum to the Sub-Collector of Paderu as they sat on an indefinite fast to demand justice. The blogpost then talks about the numerous incidents of such rapes which are left unreported with no FIRs or police complaints and dismissal of the allegations.

Land Where Impunity Is Norm - THIS ENTIRE SECTION ALSO NEEDS TO BE CONDENSED AND JOINED WITH THE FORMER AS PART OF THE MANY STORIES/ EXAMPLES. MY THOUGHT IS PERHAPS WE CAN BREAK THIS UP INTO 3-4 STORIES OF THE 3-4 WOMEN AND FORMAT IT AS SUCH FOR EASIER READING. - I agree + we definitely need to look at the flow of the story.

These unsubstantiated reports would be gladly dismissed in an outright manner, if they were not symptomatic of the vast impunity enjoyed by law enforcement in the Maoist conflict. An independent study carried out by the Jagdalpur Legal Aid Group found that till 2012, 95.7% of the criminal cases in Chhatisgarh ended in acquittal. In 2012, 14,780 inmates were lodged in Chattisgarh jails which were meant only for 5,850 prisoners – an overcrowding 253% over the national average of 112. In fact, prisons in Bastar are said to be the most overcrowded in the country with occupancy rates exceeding 400 percent in jails of Kanker and Dantewada districts.

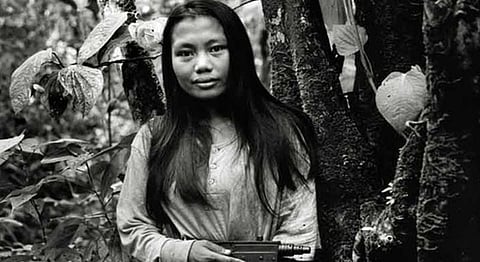

This provides credible proof of a serious investigation into the allegations made by various women against police brutality. One such famous case is that of Soni Sori, who along with her nephew, journalist Lingaram Kodopi, was arrested for being a courier between the Essar company and the Maoists for extortion money. Soni Sori has alleged extreme police brutality with electric shocks and even accused police officer by the name of Ankit Garg of raping her. Garg has gone onto collect a bravery award from the Chhattisgarh government while Soni and Kodopi languished in jail and are only out on bail since 2013 after an appeal to the Supreme Court, having spent two years in jail. Two medical reports had found serious injuries including stones in her private parts.

In an interview with Tehelka in early 2014, Soni recounted the horrors Adivasi women are subjected to in the state. “There are girls who were kept in police stations for 15 days, raped and tortured. There are others who were shot and are still languishing in jails. Some girls had to undergo operations,” described Soni as she went on to talk about meeting Hidme without naming her. “There were girls whose nipples had been chopped and given electric shocks. The girls said they had suffered and could not even expose their ghastly ordeals. Their stories gave me inspiration to survive my ordeal. They have told me not to speak of it because they fear the consequences of exposing the torture.”

Soni fights for other like her as the former teacher seeks justice while still out on bail with six of the eight charges brought against her dropped, while continuing to face threats of being jailed again for helping those in need such as Bhima Madkam, who was injured in police firing and is restricted access to family and friends.

One such brutality was meted out by the use of a state-sponsored vigilante group called Salwa Judum which was engaged in frequent assault, rape and harassment of the Adivasis. The brutal mechanism employed by the state was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court and yet, Salwa Judum is also set to regroup, further aggravating the cause of Adivasi women in the region.

The Grass Isn’t Greener On The Other Side

The treatment meted out to the Adivasis by the law enforcement and government, guilty and innocent alike, would naturally act like a push to the other side for those caught in the crosshairs of this decade old conflict. Sadly, even the movement which claims to fight for justice is swamped with numerous examples of misogyny and rape.

Shobha Mandi alias Uma/Shikha, has vividly described her experience of working as a Maoist in a book titled Ek Maowadi Ki Diary where she described how she was raped and assaulted by her fellow commanders over seven years. She was the commander of 25-30 strong Maoist group before she gave up her arms in 2010. She said that she protested such behaviour in front of senior leaders including the slain Kishenji, the leader of the Maoist movement, but to no avail as all her complaints and protests fell on deaf ears. Rape, adultery, wife swapping and even torture on women have been described as norm by her rather than exceptions.

“Every woman is seen as an object which would satisfy the lust of all male cadres. The movement had lured me in 2003 by making me believe that men and women would be equal in the new order it strives to create. But what I experienced over there was horrifying, worse than the oppression that the women of rural India face,” describes Shobha in her book. “If a member gets pregnant, she has no choice but to abort; a child is seen as trouble that hampers the lives of guerrillas”, she states, highlighting the deep misogyny embedded in the movement.

Instances of no complaints about Comrade Naveen, said to have raped a girl in the village of Curreygudem, Chhatisgarh in 2008, are replied with ‘hum itne bade aadmi ke bare mein aesa kaise bol sakte hai’ by the villagers, highlighting the impunity enjoyed by the other side through exercise of constant fear.

The police and government continue to deny the allegations put forth by various Adivasi women, insisting that these are baseless allegations made by women who are motivated by Maoists to level them to undermine the morale and legitimacy of the police, while enjoying shocking impunity which needs reprimand and inspection urgently.

The convoluted handling of the Maoist insurgency by subsequent central and state governments has resulted in a situation where the mere questioning of state’s authority or flaws is dubbed as ‘Maoist sympathy’, a manner akin to the Mc-Carthy Communist witch-hunt in America in the 50s. It’s in these dangerous times that the Kerala High Court judgement which stops a Maoist from being labelled a criminal, is a progressive step ahead.

The curtailing of a misogynistic and rape culture in the Maoist ranks lies through the path of dismantling the insurgency, either through the army operations or negotiations, a complicated solution which might take years to come into fruition. But no such leeway can be spared to the law enforcement and the governments, sworn protectors of rights and the Constitution, who must take it upon themselves to reform and end a culture of impunity through fair investigations. - I’M NOT SURE IF I’M OK WITH TAKING SUCH A CLEAR STAND ON AN ISSUE LIKE THIS. WE’RE NOT CLOSE ENOUGH TO IT IN MY OPINION & MORE THAN IDEALISM, IT SEEMS LIKE A NAIVE CONCLUSION BUT I COULD BE WRONG. EITHER WAY WOULD LIKE YOU’LL TO READ MORE ON THE ISSUE AND COME TO ME WITH SOME RESEARCH ON THE SAME. WHAT DO PEOPLE LIKE ARUN FERREIRA THINK THE WAY AHEAD IS FOR EXAMPLE? OR AN ARUNDHATI ROY VS WHAT THE GOVERNMENT THINKS VS WHAT THE MAOISTS THINK.

Until that is accomplished, no side can claim any righteous vindication for their actions as the real war, the one against women, rages on both sides.