- #HGWORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

Tucked away in Gali Qasim Jan in Old Delhi’s Ballimaran, stands the kothi which 19th century Urdu poet, Mirza Asadullah Baig Khan, popularly known as Ghalib, called home. Largely inconspicuous but for a stone plaque that identifies the building and a few odd visitors through the day, the house where Ghalib spent the last decade of his life has changed many hands since.

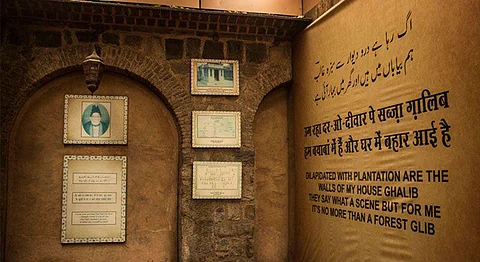

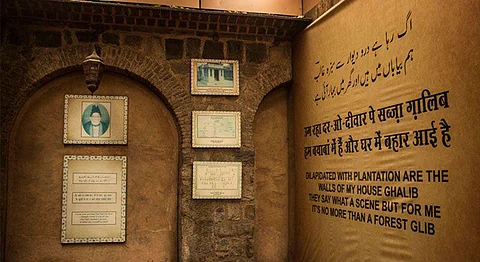

Until 1995, the haveli was a heater karkhana (factory). “Yeh toh bohot hi badi haveli thi, ab sab batwara ho gaya hai (this used to be a very big haveli, everything is partitioned now),” says Krishipal, 55, the security guard at the haveli. Today, a portion of the house has been renovated and converted into a museum in honour of Ghalib. Only the courtyard and two rooms of Ghalib’s original residence survive. The archway at the entrance now leads to Ghalib’s 19th-century courtyard on the left and a contemporary travel agency on the right.

The museum attempts to recreate the time the poet was a resident of the house. The lakhori stone of the walls, popular in many homes of the Mughal era, harks back to that time, but only cursorily. Once open-roofed, the courtyard is now covered with a fibreglass sheet to protect the exhibits from the perils of weather. The museum houses some choice couplets of Ghalib’s, printed on large canvases. A family tree of the poet, both in Urdu and English, traces his genealogy back to Samarqand, in modern-day Uzbekistan. Among other displays in the museum are replicas of original manuscripts, of his clothes, as well as of old utensils that the households may have used. A life-size sculpture of him holding a hookah, wearing the classic long, karakul topi (cap) and a muslin angrakha over a white kurta and pyjama, is a reflection of how Ghalib spent his leisure afternoons.

Ghalib moved into the haveli with his wife, Umrao Begum, in 1860 and stayed there until his death in 1869. In their near 60-year-old marriage, the couple had seven children but none survived beyond infancy, the pain of which often reflects in Ghalib’s poetry. A verse in one of his ghazals reads:

“Qaid-e-hayāt o band-e-ġham asl meñ donoñ ek haiñ

maut se pahle aadmī ġham se najāt paa.e kyuuñ”

(“The prison of grief and the bondage of life are one and the same,

why should man be relieved of this sorrow before death?”)

Life in Ballimaran

It’s befitting that a mango seller parks his cart right outside Ghalib’s haveli. The poet’s love for the juicy, summer fruit has been appropriately documented in his own letters to friends, as well as in Yaadgaar-e-Ghalib, a memoir by Altaf Hussain Hali, Ghalib’s student and biographer. A popular anecdote is of when Ghalib had accompanied Bahadur Shah Zafar to the Baagh-e Hayaat Bakhsh, the largest garden in the Red Fort. On seeing Ghalib look intently at the mangoes, the emperor was compelled to ask what he was looking for. Pat came Ghalib’s reply:

“Badshaah salamat maine buzurgo se suna hai,

daane daane pe likha hai khaane waale ka naam.

Ibn falon ka naam, ibn falon ka naam… Dekh raha hoon kisi aam par mere baap dada ka naam bhi likha hai kya.”

(Oh Emperor, I have heard from my elders that every morsel has the name of the person it is destined for. I am checking to see if any of these fruits have the names of my forefathers etched on them.)

The emperor took the hint and a case of mangoes promptly arrived at Ghalib’s house soon after.

Today, the street outside his haveli is devoid of food vendors. There are mostly shops selling spectacles and frames but it’s not hard to imagine the street bustling with eateries at one point. Ghalib, after all, loved to eat. A plaque at the museum lists his favourite dishes: fried kebabs, bhuna ghosht (roasted mutton), shami kebabs, dal murabba, sohan halwa. Ghalib sought these delicacies not only at home but even outside. The childlessness of the house and Umrao Begum’s near-fanatic piousness is said to have kept him away from home for long hours.

When he was not at mushairas (an evening of Urdu poetry reading), Ghalib liked to indulge in fine French wine and gambling, despite it being illegal and despite being neck-deep in debt. Walking through Ballimaran and neighbouring Ahata Kalay Saab (where Ghalib is also said to have lived for some time after a brief stint in debtor’s prison in 1847), one can picture the shayar (poet) sitting among friends on street corners, playing chausar or pachisi, board games developed in medieval India. Among other things, Ghalib also enjoyed playing ganjifa (a card game most likely brought to India by Babur in the 16th century) and flying kites on windy days.

The 19th Century and a City in Flux

At the time Ghalib lived and worked in Delhi, the British era had begun and the Mughal dynasty was declining. Born in Agra in 1797, Ghalib came to Delhi at the age of 13, when he wedded Umrao Begum. He lived in many rented houses in Delhi, the house in Ballimaran only being the last. Much of his adulthood was spent looking for a position among court poets who considered him an Agra wallah, an outsider. He often tussled between his two identities – ‘Asad’, his given name and what his childhood friends in Agra called him, and ‘Ghalib’ the nom de plume he gave himself.

When he couldn’t draw an income from poetry, he relied on the pension from his uncle’s estate, which was meagre and irregular. But it was in this city where his heart lay, despite the poverty-stricken days Delhi had shown him.

“Hai ab is māmūre meñ qaht-e-ġham-e-ulfat ‘asad’

ham ne ye maanā ki dillī meñ raheñ khāveñge kyā”

(There is now in this town a famine of the grief of love, Asad

We have accepted we will remain in Delhi – what will we eat?)

It was only after the death of his rival Sheikh Ibrahim Zauq in 1854 that Ghalib succeeded him as Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar’s ustad or master. Zafar himself was a gifted shayar and it was Ghalib’s duty to edit his verses. During his tenure at the court, Ghalib would reach the Qila-e-Moalla (Red Fort) by 9 am, come back home for lunch and then return to the palace, writes Delhi blogger, Mayank Austen Soofi. In the evenings, Ghalib would often be required to accompany the emperor in flying kites, Soofi adds. But royal patronage did not necessarily translate into wealth.

The mutiny of 1857 left a deep impact on Ghalib. The British suppression of the uprising led to Emperor Zafar being deposed and imprisoned, Jama Masjid and Red Fort being converted into barracks and several Muslims fleeing the city. In Dastambu, Ghalib’s day-to-day account of the scenes of the mutiny, he describes the chaos around him:

“Chowk jisko kahein, woh maqtal hei

Aaj ghar bana hei namoona zindaan ka”

(The road crossings have turned into guillotines,

each house has become a replica of prison).

In subsequent years, Ghalib described how the city he loved had become alien to him. In a letter to a friend in 1861, Ghalib wrote:

“The city has become a desert… by God, Delhi is no more a city, but a camp, a cantonment… No fort, no city, no bazaars, no watercourses… Four things kept Delhi alive – the fort, the daily crowds at the Jama Masjid, the weekly walk to the Yamuna Bridge, and the yearly fair of the flower-sellers. None of these survives, so how could Delhi survive? Yes, there used to be a city of this name in the land of Hindustan.”

Yet, despite all his heartbreak, Ghalib was careful not to incriminate the British too much in his writings. Whether this was sycophancy or simply a survival instinct is up to others to interpret. “I have eaten the bread and salt of the British,” he confessed in Dastambu.

Ghalib’s Delhi

The residents and shop owners in Gali Qasim Jan today have seen the haveli transform from godown to a museum. “We were just told this is Ghalib’s house but there used to be a karkhana there, people used to store coal,” says Mohd Tahir, 48, who runs a mechanics shop a few buildings away from the haveli. In the last few years, every 27 December, Ghalib’s birth anniversary, a mushaira is organized and admirers of the poet descend to celebrate his legacy. But does it have his spirit? “There’s no such thing as spirit or aatma. Those who have gone, have gone,” Tahir retorts.

UPSC aspirants from Kashmir, Umair Ul-Islam, 23, and Ubaid Mir, also 23, remember reading Ghalib in school when they studied Urdu. The two enjoy Ghalib’s poetry and are appalled at the state of the museum. “We can just lift these manuscripts and walk out, nobody would notice,” quips Mir. But Krishipal, the guard outside would, in fact, notice, though he had never heard of Ghalib until he was posted at the haveli six years ago.

When Ghalib died in 1869, he was still in debt and in deep, physical agony. The years he spent in the haveli in the winter of his life were not necessarily happy ones. He died famous but poor. “Duniya ki yehi reet hai, insaan ke marne ke baad hi uski qadr karte hai log, (This is the way of the world. People’s worth is appreciated only after they have gone),” says 80-year-old Mohd Aarif, who attended many mushairas in his youth.

In the city of Ghalib’s heart, Urdu is dying fast and Farsi, the Persian tongue he prided himself on, has long disappeared. It was this city that Ghalib described such:

“Ik roz apni rooh se poocha, ki dilli kya hai,

to yun jawab main keh gaye, yeh duniya mano jism hai aur dilli uski jaan.”

(I asked my soul, ‘What is Delhi?’

It replied: ‘The world is the body and Delhi its soul”)

In many ways, Ghalib may have been right about the city, with all its majestic history. But one can’t say with certainty if the soul of the city today is one that Ghalib will recognise.

If you liked this article we suggest you read: