- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

At a time when India’s racism towards the African community is becoming more and more abhorrent, or at least, apparent, it’s interesting to note how deeply our countries’ histories are entwined--filled with figures from the African subcontinent who entered our country as part of the slave trade but went on to become reformers and rulers. One such man was Malik Ambar, as he came to be known later, whose destiny demanded he become a ruler in 16th century India. Born as Chapu in 1548 southern Ethiopia, his journey to our part of the world tells the story of slave trade, the rise and fall of dynasties, and military excellence in India’s Deccan sultanate.

Tracing Ambar’s travels, leads us through caravans, dhows and more, as the young African was taken across the Red Sea to the port of Mocha in southern Arabia (Yemen), after which a slave trader sold his fate in Baghdad’s slave markets--a moment in time that defined the beginning of a chain of events that would upturn the Mughal empire. In Mocha, his Arab owner Kazi Hussein noticed his intellectual capabilities, and trained him in finance and administration as well as christened him Ambar while converting him to Islam. And by 1575, Ambar found himself sold in India to Chengiz Khan, the Peshwa of Ahmadnagar at the time.

Africa’s role in Indian history

“Early evidence suggests that Africans came to India as early as the 4th Century. But they really flourished as traders, artists, rulers, architects and reformers between the 14th Century and 17th Century,” said Kenneth Robbins, co-curator of an exhibition on ‘forgotten’ stories of Africa’s role in Indian history at the New York Public Library. As many African slaves were sold and resold into India, Ambar was a member of this mass movement eastward. While locally in India African slave migrants were termed as Sidis (now a tribe with scheduled caste and tribe status) connoting a higher status, they were more commonly referred to as Habshis—people from Abyssinia.

Chengiz Khan, who was a Habshi himself, instilled Ambar with knowledge regarding Indian political, military and administrative affairs. After Khan’s death, different accounts relate contrasting stories regarding Ambar’s future, but the most accepted version believes Ambar was eventually sold to the King of Bijapur, who, impressed by his skill and intellect, bestowed upon him the title of ‘Malik’, meaning ‘like a king’. Still, Malik Ambar was born to lead, not follow.

A leader is born

In the book Man, Know Thyself: Volume 1 Corrective Knowledge of Our Notable Ancestors, Rick Duncan states, “Malik Ambar was made military commander of the King’s army and after some time, when the King refused to finance trainee soldiers, the frustrated Ambar took his soldiers with him and became an independent mercenary army who hired their services to various Kings and Sultans in Deccan culture.” And this began Malik Ambar’s military prowess in India’s Deccan.

While various sources retelling this historic tale might argue over how exactly Malik Ambar gained control of Ahmadnagar with himself as the Regent Minister, the popular story is that he imprisoned the King of Ahmadnagar and took the title. Further, he cemented his rulership by marrying off his daughter Murtaza to Ibrahim Adil Shah II, son of former Deccan ruler Shah Ali.

As Regent, he founded a new city and capital called Khadki, later Aurangabad, and launched several long term architectural projects. His innovative and wildly sophisticated water supply system, later known as Aqueduct, was one amongst his many planning trump cards. Introducing a new systematic revenue system based on land measurements, he created a farmers tax system that several Deccan settlements continued to follow. Still, the legacy he left behind was the unified force he harnessed to keep the Deccan Sultanate out of Mughal hands.

The Deccan Sultanate and Ambar’s rise to military power

As a military expert, he employed guerrilla tactics and trained his army to become a strong force against Emperor Akbar as well as Jahangir, and he didn’t do it alone. As The Muslim Diaspora, 1500-1799 by Everett Jenkins, Jr. states, “Upon consolidation of his power, Malik Ambar organized an estimated 60,000 horse army. His light cavalry was very effective as a mobile unit. Malik Ambar also enlisted the naval support of the Siddis (fellow Africans) of Janjira island in 1616 in order to cut the Mughal supply lines and to conduct harassing missions.” Riksum Kazi, author of a TCJN Journal paper on Malik Ambar’s life and legacy, recounts how Ambar recruited anti-Mughal soldiers and led an army of highly skilled Abyssinians, Marathas, and Muslims from the Deccan.

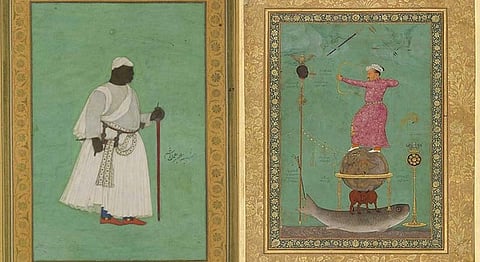

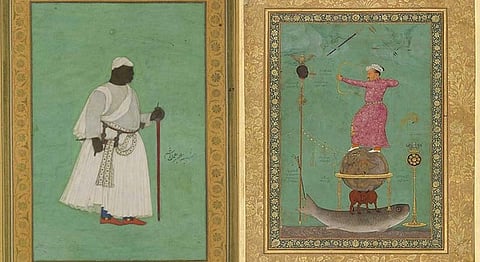

When Janagir ascended the Mughal throne, he inherited his father’s loathe for ‘Ambar of dark fate, that disastrous man’. His memoirs refer to the African sultan as a rebel, a usurper, a plotter. Embodying this sentiment is a famous painting with Malik Ambar’s head on a stick, being shot at with an arrow by none other than Jahangir in royal robes. The emperor commissioned the creation of this work of art in 1615, representing the Mughal hunt for Ambar’s head. Ironically, Jahangir never actually got to defeat Ambar, despite the will of his painter’s brush.

The legacy he left behind

Accounts of Malik Ambar’s heroic rise in India’s military ranks feature in several historical records of the African diaspora in Asia. As the Encyclopaedia of Antislavery and Abolition remembers him, “Ambar, who died in the 1620s, is remembered as having been not only a good commander and administrator, but also a great builder. He established Ghurkeh, later named Aurangabad, and decorated it with a magnificent palace and gardens. He was by far the most famous of the Muslim Siddis of India who survived either as part of the Deccan nobility or more commonly as farmers and poor unskilled workers. Ambar’s remarkable career represents how some slave-soldiers used the military as a path out of slavery.”

Still, apart from being a savvy opportunist and strong military leader, Malik Ambar’s legacy in India is one of great historical relevance. As The New Cambridge History of India: A social history of the Deccan, 1300-1761 rightly puts it, “Yet Malik Ambar’s career can also provide a window onto a range of other issues pertaining to the social history of the Deccan—issues of race, class, or gender, and especially issues related to the institution of slavery.”

If you liked this article, we suggest you read: