- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

‘Trapped in Transit With No Next Flight in Sight’

Text: Pallavi Rebbapragada

[This article was originally published on Sunday Standard on April 3 and is being republished on Homegrown with permission.]

Less than a month after Indira Gandhi was assassinated in 1984, a girl was born in Erbil, the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan. The young mother was distantly infatuated with the charismatic personality of the deceased Indian prime minister, and paid special attention to it on radio news bulletins in between songs from Shashi Kapoor and Shammi Kapoor movies. The admiration for India’s openness got her to name her daughter Hind, which stands for India in Arabic. Today, Hind lives as a refugee on the outskirts of Delhi with her husband Ahmed and their daughter. “In the country I am named after, I am waiting for my turn to live. I guess it was all meant to be,” says Hind, and smiles at life’s ironies.

Hind went to college in Dora that lies in the South of Baghdad. “My brother used to drive me to college and I had to be back by 1 pm. The US Army lost 1,500 soldiers near my home. Before the occupation, it was possible to go to cafes and wear jeans; there was more freedom,” relives Hind. Her degrees were thrown at her face by employers because she was Sunni.

Hind isn’t alone. There are 43 refugees and 28 asylum seekers from Syria and 304 refugees and 166 asylum seekers from Iraq registered with UNHCR in India, and each story is dreadfully distinct from the other. While 250,000 Syrians have lost their lives in the ongoing violence, lakhs have fled the carnage of ISIS dominated areas after the terrorists swept into Mosul and other cities along the Syrian-Iraqi border, announcing the return of the Caliphate, a system of Islamic rule. ISIS now controls a territory as large as the UK with a population of six million people, many searching for a passage to Europe and Asia.

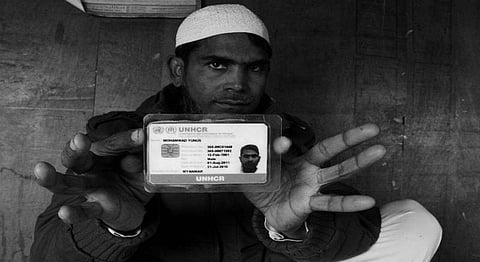

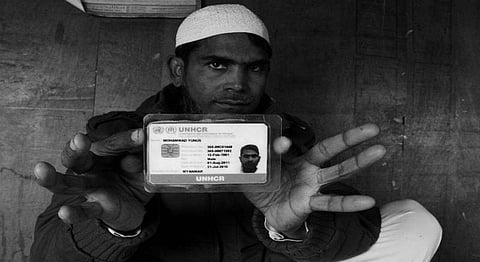

Hind’s husband came here on a student visa in 2010. In 2013, he flew back to Baghdad only to realise his life was in peril. His valid student visa helped him escape. This family’s Long Term Stay Visa (LTV) documents are pending with the foreigner regional registration offices (FRRO) since November. Their only identification is the UNHCR refugee card that isn’t accepted by most authorities and even the local police; they cannot book flights, get an Internet connection or install a gas pipe.

Those who were washed ashore by the calamitous political tsunami that is Syria have their own stories. Farhat (name changed) will turn 30 in a couple of months. Trained in IT in south India, he left Syria before the civil war erupted. One of his friends is trapped in a camp under siege by the ISIS and Al-Qaeda. He has eaten frogs, grass and even his cat to survive. Back home, Farhat’s options were limited to joining the Al-Li-Jan-Al-Shabiya or the public forces. In New Delhi, his problems are different. He wants to save up $600 to get his Syrian passport renewed so he can leave India. He feels his chances of saving that amount seem grim, because most jobs he finds pay him not more than Rs 15,000. In a windowless room deep inside a Delhi ghetto, where cars, buses and fresh air don’t go, he smokes one beedi after another and contemplates whether suicide is a better option than going on a hunger strike.

Rifat (name changed) is a Syrian cook and is waiting for a UN shuttle to ship him and his four children to another country, where he can send them to Arabic school. He works at a hole-in-the-wall restaurant and specialises in making Warbat bi-qishteh, the Arabic version of Baklava. Anas (name changed) fled Syria on an Indian tourist visa. Both his home and his shop were reduced to debris. Before the war, one dollar was 50 Lira which depreciated to 500 Lira. India might have offered refuge to his family of three, but they are surviving on his wife’s gold.

Life in India is survival from the devil, but not from diving into the deep sea. Firstly, India does not have a domestic asylum law. “The term refugee doesn’t find mention in any legislation. While some proposals were introduced in Parliament in 2015, there has been no progress so far,” says Roshni Shankar, executive director of the ARA Trust. This Delhi-based centre for law and policy assisted in the drafting of the Asylum Bill in 2015. If the Bill is passed, it will introduce a codified domestic law for the identification and recognition of those who qualify for refugee status, and establish a transparent and legally sound procedure for the determination of asylum claim for people like Mushtaaq (name changed). He is a 25-year-old software engineer from Iraq and is Shia, but militants mistook him for being Sunni. “I grew my beard to hide the scar they left on my chin. I was being forced to join the militia. I will not kill innocent people to save my life,” he confesses. In 2004, his father was killed by the US Army in Baqubah and he doesn’t know if his mother is still alive. He came to India a year ago and applied for the UNHCR’s refugee card shortly after. Till it comes through, a thin sheet of paper (a faded UN blue) upon which a new expiry date is stamped every couple of months is what saves him from deportation.

Omar, also Iraqi and in his late 20s, doesn’t want to go back to his home in Ramadi. “When I went back last to last year, my family risked their lives to receive me at the airport. Roads leading inwards were sealed,” he says, citing the example of his father-uncle whose younger cousin went missing earlier this year. Omar, who came here on a student visa and is now a refugee, wants to do academic research. Jawaharlal Nehru University declined his fellow refugee friends’ applications. “What will anybody get by educating us?” he asks.

Being a refugee is like being in transit with no next flight. Can’t tell if they are healthy patients or faultless prisoners, or ticketless travellers. They are their painful pasts, they are their residual futures and for such reasons, they are excused from the pressure of being present in their present.

Vis–a–Wish

■ Sources from the UNHCR in Delhi state that Long Term Visas (LTVs) regularise the stay of refugees in India, enhance employment opportunities in the private sector and enable easier access to higher education. Due to the UNHCR’s continued advocacy, LTV processes have been simplified and expedited by the government to ease refugees’ access to them.

■ According to ACCESS Development Services (a livelihoods organisation that implemented the ‘Refugee self-reliance and livelihoods’ project in Delhi & NCR), refugees from Iraq and Syria are technically qualified and have a working knowledge of English as compared to the Myanmarese refugees who are mainly agriculturalists.

■ The refugee law will give them legal right to remain in India. It will also give refugees a measure of social security during their stay in India, such as access to education and healthcare and the right to work, to a limited extent.