- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

In a world now smitten with the likes of kombucha and kimchi, it’s easy to overlook how deeply fermentation runs through Indian kitchens. Long before these jars took over our fridges, we were sipping kanji in the winter sun, steaming idlis for breakfast, and ladling out dahi with lunch. Meanwhile, in a quietly humming Parsi pantry, taari — a toddy drawn from the sap of palm trees — has always held its own.

Taari is drawn from the sugar palm, coconut palm, or date palm. For the Parsi community, particularly those along the coastal stretches of southern Gujarat, it isn’t just a drink — it’s a way of cooking, preserving, flavouring, and sometimes even healing.

Throughout the ’70s and ’80s, taari travelled from the palm groves of Gujarat to kitchens across Maharashtra, packed in glass bottles tucked into aluminium containers. Fermentation, of course, doesn’t pause for transport, so a bit of flour was stirred in to calm the fizz and prevent the glass bottles from bursting during the journey (Conde Nast Traveller, 2024). However, nothing in a desi kitchen is ever merely functional. That taari-flour mix made its way into the batter bowl, resulting in bhakras (fried Parsi cookies), popatjees (plump fritters), or karkarias (banana fritters). Taari also had a medicinal side. Warmed with ginger and jaggery, it became a go-to home remedy for an upset stomach or a cold. One of the rarest dishes still calling for it is the Gujarati Parsi taari-no-batervo, a slow-cooked mutton stew made with reduced toddy.

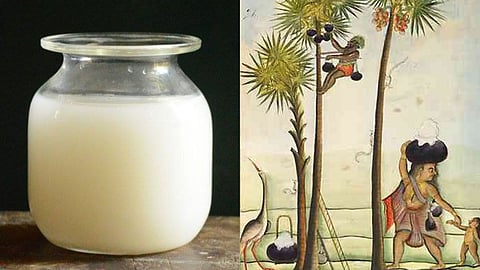

Tapping toddy is a fading art. It usually runs in families and requires climbing tall palms, tying clay or metal pots near the flower clusters, and collecting the sap from the tree before sunrise. If done early enough, you get neera — a sweet, unfermented palm nectar. Wait too long, and fermentation sets in, turning neera into taari. In coastal southern Gujarat, especially around villages with strong Parsi and Irani roots, the climate and soil still permit pockets of palmyra farms. Tappers in southern Gujarat often work on contract, collecting toddy from trees on Parsi properties in exchange for a portion of the day’s harvest.

For the Parsi community, taari isn’t just an ingredient — it’s part of a way of life, a reflection of how they’ve adapted to their environment with ingenuity and care. It was so ingrained in Parsi culture that in 1570, a few priests refused to indulge in taari during certain religious periods (Saveur, 2021). A lot has changed since 1570, but you’ll still find taari sneaking its way into stews, biscuits, dumplings — and every now and then, a generational cure for a bad stomach.

If you enjoyed reading this, here's more from Homegrown:

Inside Parsi Fire Temples, Where You’ll Never Get To Go

The F.D. Alpaiwala Museum: Mumbai's Only Parsi-Zoroastrian Museum Reopens To The Public

When Parsi Aunties Hosted One Of Mumbai’s First Foreign Rock Concerts