- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

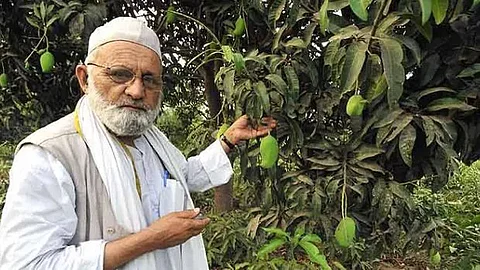

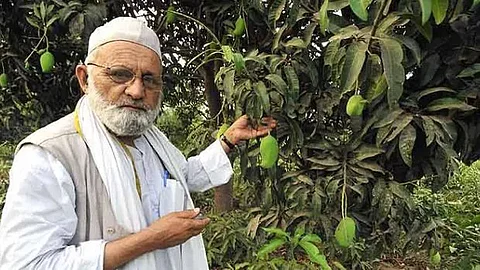

The mango, king of fruits, has been cultivated for centuries in India. From the orchards of Malihabad to the royal tables of the Mughals, mangoes are a symbol of culture, tradition, and innovation. But even in this vast, mango-loving nation, one tree stands apart from all others — a singular marvel that bears over 300 varieties of mangoes. Behind this wonder is the determination of one man: Kalimullah Khan, better known as India’s ‘Mango Man’.

Born into a family of farmers in Malihabad, Uttar Pradesh, Khan’s life was steeped in agriculture from an early age. Unlike many of his peers, who focused on conventional farming, he was drawn to the science and art of grafting. His fascination with crossbreeding began when he saw a rose bush in his friend’s garden bearing flowers of different colours. If a single plant could produce multiple shades of roses, he wondered, could a tree grow multiple kinds of mangoes?

At 17, Khan attempted his first grafting experiment, combining seven different mango varieties onto a single tree. A flood destroyed his early work. Over the decades, he perfected his techniques, transforming grafting from a method of cultivation into an art form. His magnum opus is a 100-year-old tree that bears over 300 varieties, each distinct in taste, texture, and colour.

Khan’s legendary tree is nothing short of a botanical anomaly. On its sprawling branches hang mangoes of all shapes and sizes — round, oblong, kidney-shaped — each ripening in different hues of yellow, orange, red, and even purple. Among the countless varieties, you can find the Alphonso, with its rich saffron pulp, the tangy Langra, the aromatic Dasheri, and even the Tommy Atkins mango, originally from Florida.

For Khan, each mango has a personality of its own. Some are robust and fibrous, others melt-in-the-mouth creamy; some are intensely sweet, while others strike a perfect balance between tart and sugary. He has even named new varieties after cultural icons, including Sachin Tendulkar, Aishwarya Rai, and Narendra Modi. During the COVID-19 pandemic, he named two new varieties “doctor aam” and “police aam” in honour of frontline workers.

Khan’s innovation is based on the technique of grafting, an age-old practice where a branch from one tree is joined onto another, allowing them to grow as a single entity. This method is widely used in commercial agriculture to enhance productivity and resilience, but few have taken it to the extremes that Khan has. His intricate process involves slicing, fusing, and nurturing different varieties onto his base tree, ensuring that each retains its unique characteristics.

Beyond being an artistic pursuit, his work has practical implications. As climate change threatens traditional farming methods, grafting offers a means to cultivate harder varieties and optimise fruit production. His techniques have drawn interest from researchers and farmers in Iran and Dubai, where he has been invited to share his expertise.

Khan’s dedication has earned him national and international acclaim, including the prestigious Padma Shri, one of India’s highest civilian honours. His name features prominently in the Limca Book of Records, and visitors from across the world flock to his orchard to witness his miracle tree. His contributions to horticulture have been hailed as revolutionary, and yet, not everyone shares his enthusiasm.

Critics argue that Khan’s work, while remarkable, lacks commercial viability. The Mango Grower Association of India has dismissed his creation as a showpiece, pointing out that large-scale mango production depends on consistency, something his experimental tree does not offer. Khan, however, remains undeterred. For him, the goal was never mass production but rather the preservation and celebration of mango biodiversity.

Despite his age, Khan remains active in his orchard. He does not sell the fruits from his legendary tree but instead shares them with visitors. His farm is a living laboratory, a museum. As the world shifts towards monocultured farming and industrialised agriculture, Khan’s work is a reminder of the importance of biodiversity. His tree, a microcosm of India’s rich mango heritage, is a symbol of resilience, ingenuity, and an undying love for the fruit that defines a nation.

Learn more here.