- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

Urdu Shayari (poetry) has always embodied a progressive spirit, pushing forward anti-fundamentalist ideas as well as playing an important part in the broadening of romantic traditions in the orient. The language has been integrated into our colloquial speech and has dramatic effects on the culture and literature of generations. Ghazals, Shers and Nazms (forms of poetry), penned down during the freedom struggle are etched in our collective consciousness and even offer a chronological timeline through which we can revisit the different phases of India’s journey towards independence.

While most people can recognise the work of Mirza Ghalib, very few are familiar with women who have pioneered Urdu poetry. Rekhti, a form of feminist Urdu poetry uses a female voice and was initially developed by male poets, namely Saadat Yaar Khan Rangin. It presented an unabashed view of female desire and soon was taken up by women who even spoke of same-sex love, all the way back in the eighteenth century!

Bold and explicit at times, Rekhti gave a female speaker agency; divulging in stories associated with feminine lifestyles and situations encountered by wives, concubines, courtesans, and servants. The democratic and diverse form of storytelling furthered the female expression in Shayari and although Rekhti soon became less common over the years, it helped curate a space for women in Urdu poetry.

Maha Laqa Chanda, a courtesan by profession, was the first female Urdu poet to get published in the Indian subcontinent and paved the way for many more to come. Her story echoes a spirit of resilience against all odds, born as Chanda Bibi in 1768 she read and acquired mastery in several skills such as archery and horse-riding at a young age. She dared to write at a time when poetic gatherings were restricted to men.

Inverting the norms, she made a name for herself in a widely male dominant poetry scene of 18th century Hyderabad. She calligraphed thirty-nine poems in a diwan (compilation of Urdu poetry) titled Gulzar-e-Mah Laqa, becoming the first woman to get her poetry published, thus claiming a position of power for herself and for more women to follow through with the craft of writing.

The Women Who Continued To Pioneer Urdu Poetry

Ada Jafri, known as the first lady of Urdu poetry experimented with free verse. Her work revolves around feminism, speaking at length about the dehumanization of women in society. Similarly, Fahtima Riaz, a controversial poet of her times, held firm beliefs and often penned down her ideas as a human rights activist. Her prolific work has been noted alongside Pablo Nerurda and Nazim Hikmet.

Sara Sahgufta, who faced hardships and accusations for her work throughout her life, held a powerful presence in the literary world and was hailed as the Sylvia Plath of the subcontinent by the famous Indian novelist, Amrita Pritam. The poet lost her life to suicide at a young age but her work still furthers conversations of female empowerment around the world.

Kishwar Naheed, a feminist Urdu poet from Pakistan documents the experience of countless women who are subjected to patriarchal norms which further perpetuates gendered violence even in recent times. Her work often claims space for female bodily autonomy, speaking against regressive practices that view a woman as the sole property of men.

Magar mujhe makkhī jitnī āzādī bhī tum kahāñ de sakoge

(But you can’t even give me the kind of freedom the fly enjoys)

Tumne aurat ko makkhī banākar botal meñ band karnā sīkhā hai.

(You have learnt to imprison women like you imprison flies in the bottle.)

— Kishwar Naheed

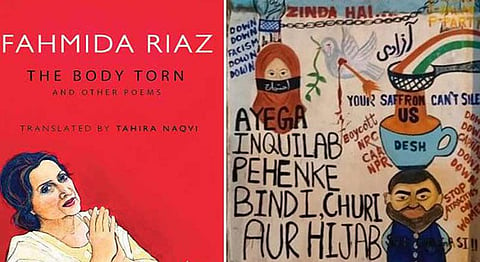

In recent years, female Urdu protest poets such as Nabiya Khan, a young history student, are becoming the voice of dissent in the current political turmoil. Her latest poem ‘Ayega Inquilab Pehene Ke Bindi, Chudiyan, Hijab’ (Women Will Lead The Revolution) was widely used as graffiti on posters and placards during the Shaheen Bagh protests.

Urdu poetry continues to act as a tool of resistance and women, in particular, have furthered progressive ideas through their craft. The non-conformist ethos of the art form is a vessel for change and through the words penned down by the immortal female Urdu poets, this spirit of resilience is carried forward.

If you enjoyed reading this, we also suggest: