- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

What happens when two people tell vastly different versions of the same story? When those people belong to different cultures, genders, and worlds — one a Western man, the other an Indian woman — the stakes go beyond personal memory and dive into the murky waters of power, representation, and truth. This is the tension at the heart of 'La Nuit Bengali' (Bengal Nights) Mircea Eliade and 'Na Hanyate' (It Doesn’t Die) by Maitreyi Devi. Two interwoven narratives about a brief romance erupt into a decades-long battle over storytelling. Whose version prevails? What does this literary tug-of-war reveal about the stories we tell and the silences we impose?

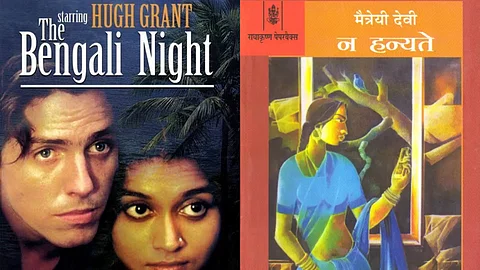

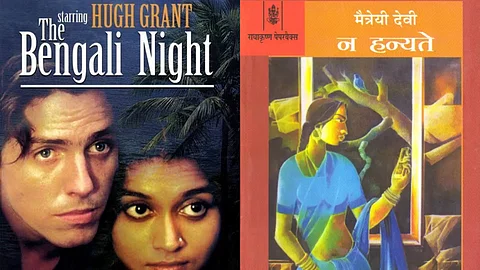

At the heart of these books is the real-life encounter between Mircea Eliade — a Romanian philosopher and scholar — and Maitreyi Devi — an Indian poet and protégée of Rabindranath Tagore — in 1930s Calcutta. Eliade, then a young academic studying under Devi’s father, wrote 'Bengal Nights' in 1933, framing their brief relationship as a passionate but tragic romance disrupted by cultural and familial constraints. Devi, after discovering Eliade’s account decades later, published 'It Doesn’t Die in 1974 as a response, challenging his interpretation.

These books were more than personal recollections. They reflected the broader dynamics of colonialism, cultural misunderstandings, and gendered power imbalances. Eliade, a Western outsider, wrote from a position of privilege, both as a man and as a member of the colonising class, while Devi’s account sought to resist that lens and reassert her perspective as a woman from a colonised society.

Eliade’s Bengal Nights portrays the story as a passionate, doomed love affair between Alain (his fictionalised self) and Maitreyi, hindered by cultural taboos and the conservative authority of her father. In this version, Maitreyi emerges as an exoticised, almost mythical figure — a symbol of India’s sensual allure. His descriptions, however, teeter on the edge of caricature, reducing her to a manifestation of his Orientalist fantasies. For instance, her “brown arm” becomes an object of both desire and dehumanisation, conflating her individuality with the archetype of a mysterious Eastern muse.

The University of Chicago PressDevi’s, It Doesn’t Die, on the other hand, dismantles this narrative with clarity. Far from being a passive object of Alain’s fantasies, her account portrays her as a self-aware individual grappling with the emotional and social consequences of their relationship. She frames Eliade’s actions as a betrayal — not just of her trust but also of cultural norms and familial bonds. By the time she discovers his book, decades later, she feels doubly wronged: first by the relationship itself and then by its public misrepresentation.

The dissonance between these two accounts forces us to confront the politics of storytelling. Eliade’s novel was celebrated in Europe, translated into multiple languages, and framed as semi-autobiographical. The narrative aligned neatly with colonial tropes of the West’s discovery of the East. It presents India as a land of both seductive mysteries and insurmountable cultural barriers. This romanticised perspective, while appealing to Western audiences, erased the nuances of Devi’s identity and the complexities of the cultural context.

In contrast, It Doesn’t Die emerged as an act of reclamation. Devi’s narrative not only reasserted her autonomy but also highlighted the broader implications of being misrepresented in a colonial and patriarchal framework. Her decision to write in Bengali first, before the book’s eventual translation, signified her commitment to addressing an Indian audience on her terms. In her account, Eliade’s interpretation is not just flawed but indicative of the broader interplay of cultural appropriation and the silencing of marginalised voices.

Both books grapple with the elusiveness of truth, especially when filtered through personal memory and cultural bias. Eliade, in his later reflections, acknowledged the fictionalisation in his narrative, yet he maintained an air of detachment, framing his account as a product of youthful folly and literary license. Devi, on the other hand, confronted the ethical dimensions of storytelling, particularly when the story involves the representation of another person’s life.

Their diverging accounts also reflect the broader tensions between colonial and postcolonial narratives. Eliade’s work exemplifies how colonial-era literature often projected the West’s fantasies onto the East. Devi’s response underscores the necessity of challenging these distortions and reclaiming the power to define one’s story.

The simultaneous publication of the two books in English in 1994 by the University of Chicago Press highlighted the inherent challenge of discerning truth in competing narratives. The pairing invited us to adjudicate between the two, but such a binary approach risks oversimplifying the nuances of memory and storytelling.

Rather than asking which is 'truer', perhaps the more meaningful question is what these narratives reveal about the ways we interpret and represent each other. Both Eliade and Devi constructed their stories within specific cultural, historical, and personal frameworks, and their accounts serve as mirrors, reflecting not just their relationship but also power, identity, and representation.

The stories of Bengal Nights and It Doesn’t Die compel us to consider the ethical responsibilities inherent in telling stories about others. They remind us that no story exists in a vacuum. Every narrative is shaped by the storyteller’s perspective and the audience’s expectations. These two works stand as a testament to the complexities — and consequences — of storytelling. As readers, our task is not to choose sides but to engage with the tensions and contradictions these stories embody, recognising that the 'truth' is often less about absolutes and more about the dialogue between competing perspectives.