- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

On 8 April 1929, two young men entered the Central Legislative Assembly in New Delhi — the lower house of the British Indian government — and threw feeble bombs into the Assembly Chamber from the Public Gallery, injuring some members of the Council. They were inspired by Auguste Vaillant, a French anarchist who had bombed the Chamber of Deputies in Paris in 1893. The young revolutionaries could have left in the chaos that ensued if they wanted to — instead they stayed back and threw leaflets to echoing cries of "Inquilab Zindabad", long live the revolution. They were both subsequently arrested.

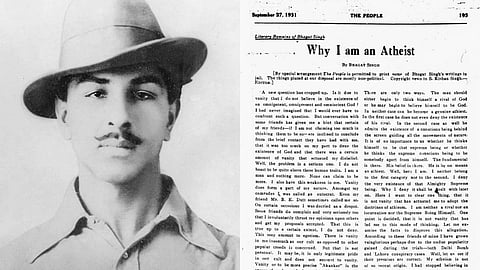

Their names were Bhagat Singh and Batukeshwar Dutt. Singh and Dutt were prominent members of the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA), a radical left-wing revolutionary organisation. Prior to the Legislative Assembly Bombing, they were involved in the assassination of John P. Saunders, an Assistant Superintendent of Police, to avenge police brutality against Lala Lajpat Rai, an act of aggression which eventually led to Rai's death. During the trial and special tribunal that followed, more members of HSRA were arrested, and eventually Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev Thapar, and Shivaram Rajguru were convicted of Saunders' murder. At 7:30 PM on 23 March 1931, the men were executed by hanging in the Lahore jail. Their remains were cremated under the cover of darkness near the Ganda Singh Wala village, and their ashes were dispersed into the Sutlej river. Bhagat Singh was only 23 years old at the time.

Their martyrdom for India's freedom struggle made Singh, Sukhdev, and Rajguru household names in Punjab and the rest of British India. Till date, Singh remains a significant figure in India's national mythology. Both Hindu nationalists and Gandhian liberals claim him as their own, but Bhagat Singh defied such categorisations during his life, and his legacy continues to defy such categorisation long after his death. He combined revolutionary militant action with Marxist ideological clarity. It is easy to lose sight of Singh as a man in the mythology that engulfs his legacy, but he was a revolutionary, a nationalist, a communist, an anarchist, an atheist, and above all, a rationalist.

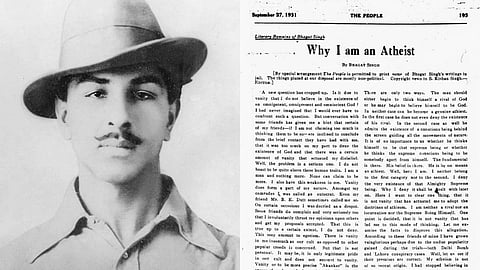

An avid reader and a gifted writer throughout his brief but eventful life, Singh continued to write during his incarceration in the Lahore Jail leading up to his execution. If anything, his imprisonment and his awareness of his looming death added a certain edge and a sense of moral and ideological clarity to his writing. Singh's seminal essay 'Why I Am An Atheist' was written in prison, in early October, 1930, somehow smuggled out, and published in The People, the newspaper founded by Lala Lajpat Rai. His last testament 'To Young Political Workers' was also written in prison in February 1931, and published posthumously.

Singh explained and reasoned his religious, philosophical, and political ideas, beliefs, and visions for a rational society at great lengths in both these documents. In 'Why I Am An Atheist', he wrote, "Society must fight against this belief in God as it fought against idol worship and other narrow conceptions of religion. In this way man will try to stand on his feet. Being realistic, he will have to throw his faith aside and face all adversaries with courage and valour." He called on Indians to "capture political power (...) by masses for the masses" in 'To Young Political Workers'.

Near the end of 'To Young Political Workers', Singh outlined the following goals: 1. Abolition of Landlordism; 2. Liquidation of the peasants' indebtedness; 3. Nationalisation of land (...) to improved and collective farming; 4. Guarantee of security as to housing; 5. Abolition of all charges on the peasantry except a minimum of unitary land tax; 6. Nationalisation of the industries and the industrialisation of the country; 7. Universal education; and, 8. Reduction of the hours of work to the minimum necessary.

The clearest and most precise declaration of Singh's vision came in his last petition written sometime before his execution and addressed to the Governor of Punjab. In the letter, Singh wrote:

"The days of capitalist and imperialist exploitation are numbered. The war neither began with us nor is it going to end with our lives. It is the inevitable consequence of the historic events and the existing environments. Our humble sacrifices shall be only a link in the chain that has very accurately been beautified by the unparalleled sacrifice of Mr. Das and most tragic but noblest sacrifice of Comrade Bhagawati Charan and the glorious death of our dear warrior Azad."

An archive of Bhagat Singh's writings is available here.