- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

At a dusty railway platform in 1800s India, a boy climbs into a wicker basket. A magician circles, chanting softly. With a flash of silver, he plunges a sword into the basket — once, twice, again. Gasps ripple through the crowd. Moments later, the boy re-emerges — grinning and unharmed.

When you think of magic, velvet-draped stages spring to mind. But in India, magic lived in the streets, temples, and stories of everyday life. Magicians didn't perform tricks in the modern sense. They rolled theatre, ritual, and belief into one. For centuries, Indian magic was a respected craft, tied to religion, healing, and oral tradition, not deception. But what happens when an empire sees wonder as superstition and outlaws the very hands that created it?

This is the story of how magic in India was made to disappear — not through sleight of hand, but through the far more brutal illusion of colonialism.

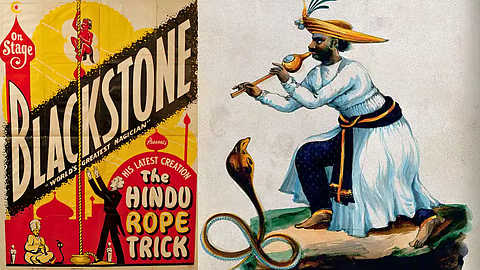

Secrets and sideshows are what we tend to think of magic as today. In ancient India, however, the concept of maya — illusion — runs through Hindu philosophy. Gods like Indra were believed to control reality through 'Indrajaal', translated literally as 'Indra's net'. Yogis halted their pulses; Fakirs walked across coals; street magicians made mango trees grow from seeds in minutes. These performances reflected a worldview where the mystical and the real were not opposites, but part of the same fabric.

Magicians, often from marginalised communities, were keepers of this knowledge. Street corners, village fairs, and temple grounds were their performance locations of choice. They were healers, fortune tellers, escapists, illusionists and storytellers of the highest order.

When the British arrived, they brought a way of seeing the world that had no room for magic (along with many, many guns). Anything that defied logic or scientific explanation was quickly dismissed as superstition. The magician, once a respected figure, became a symbol of backwardness.

Then came the laws. The most infamous was the Criminal Tribes Act of 1871, which branded entire communities — including jugglers, snake charmers, fakirs, and other traditional performers — as “hereditary criminals”. Surveillance, arrests, and public suspicion followed. Magic, once protected by tradition was now punished by the state.

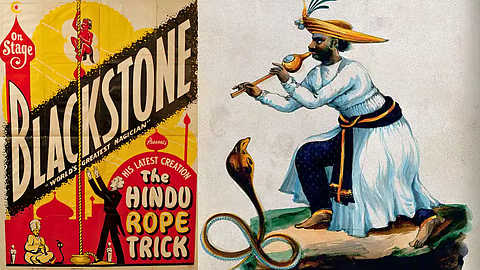

Meanwhile, British fascination with the East was growing. They stole not only India’s wealth, but also its wonder. Western magicians began to borrow and mass-market Indian tricks. From the rope trick to the basket trick to sword swallowing: all were lifted, repackaged, and sold to Western audiences. Harry Houdini started his career performing as an 'Eastern Fakir.' His act made millions but the Indian originals were left invisible and impoverished.

Some Indian magicians, like P.C. Sorcar, fought their way to global fame. Sorcar's 1956 BBC broadcast — where he appeared to saw his assistant in half just before the programme abruptly ended — sent British audiences into panic. It was a masterstroke of showmanship. But Sorcar’s success masked the reality. For every star who made it to the West, thousands of street magicians were left behind, driven out by outdated laws and shrinking public spaces.

Even after independence, colonial laws like the Bombay Prevention of Begging Act continued to criminalise street performance. To do magic in public today, many performers must pay bribes to local police — or risk being beaten or jailed.

As cities modernised, public space for spontaneous performance vanished. Younger generations left magic behind for call centres, coding, and classrooms. There were no apprentices, no stages, and little dignity left in the trade.

The real tragedy is the loss of everything that came with its decline. Magic was a vessel of collective memory. It blurred lines between science and faith; body and spirit; art and survival. It told stories in a way textbooks couldn’t. Its disappearance is a symptom of a larger erasure: of languages, professions, beliefs, and ways of life deemed “unmodern” or unfit for a rational world.

Today, when Indian magic appears, it’s often in exoticised fragments — props in travel brochures, nostalgic references in cinema, or occasional viral videos. But behind those fragments lies a history of knowledge, performance, and resilience that colonialism broke and modern India never quite rebuilt.

The magician lifts the cloth, and the object is gone. But unlike the mango seed or the coiled rope, this vanishing wasn’t an illusion.

If you enjoyed reading this, here's more from Homegrown:

Art, Dialogue, & Community: Bengaluru's Cafe Zubaan Serves Up Far More Than Food

HG Streams: Pardesi, An Indo-Soviet Film Based On The Travelogues Of A Russian Traveller

Vinayvvs' Carti-Esque EP Grapples With The Hollow Nature Of Modern Happiness