- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

There hasn’t been a more socially and politically relevant documentary coming out of India in recent times than Nakul Singh Sawhney’s Muzaffarnagar Baaqi Hai. It is the documentary whose screening has been repeatedly disrupted over the years; the one that Rohith Vemula fought to host a viewing of before his death. The controversial documentary that is said to call out the role of politicians, the BJP, more so the VHP for the role they played in fuelling the fires of the 2013 Muzaffarnagar riots in Uttar Pradesh. Three years since it was made, Muzaffarnagar Baaqi Hai is now available for streaming for the public on Netflix.

Sitting down to finally watch the film that I’ve spent countless days trying to find online, or a screening close to me, made me a bit jittery. Would it live up to the fear that the right-wing volunteers had in their minds when they would disrupt the screenings at Universities? What would it be like to watch this movie, for me, with my very Muslim surname, yet liberal upbringing? What impact can this have, now, today, in the religiously tense climate of India with the Elections on the horizon next year?

Lest it be forgotten in our country’s growing repository of hate crimes, mob violence and lynchings, communal violence broke out in Muzaffarnagar in September of 2013 leaving over 50 people dead and thousands displaced, fleeing from the bloodshed. With conflicting reports and witness statements, the real ‘cause’ of the riots differs from opinion to opinion, the harassment of a young girl allegedly being the tipping point of tensions that had been brewing (or made to brew) between the two communities.

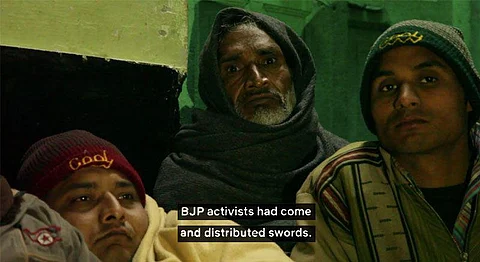

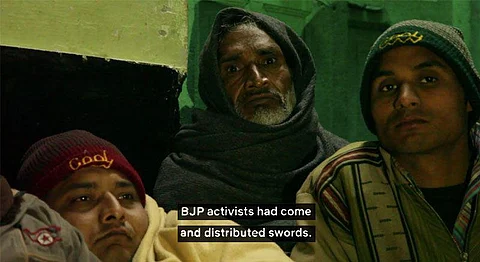

Nakul Singh Sawhney, an FTII graduate, presents his analysis from the ground in Uttar Pradesh over the 2-hour-long documentary. Broken into parts, through the film he interviewed people affected by the violence, people from the districts of Shamli and Muzaffarnagar, the grassroots activists and more, collecting tales that range from haunting to ones that just leave you angry.

Right from the onset, we see the kind of impact the violence had on the families that were witness to it. “They came to shoot us,” says a young girl retelling the tale of how her father’s head just about missed a bullet, how she grabbed her younger brother and ran. These were people who had to literally, physically run for their lives. We see abandoned, desolate houses, belongings left behind by families who made their way to ‘relief camps’ with the bare minimum resources available. Through Sawhney’s interviews of people living at the camps, we get a glaring sense of the days’ events – stories of looting, death, being burnt alive, ones of sheer depravity, human nature at its most feral state. Mostly, the sentiment that reverberates from many accounts is that of disappointment and disbelief that the people they once lived with, worked with, grew up with could overnight become their enemies, for reasons they couldn’t wrap their heads around.

How then, did a place once known as “Mohabbat Nagar” for its homogeneity and harmony turn into the site of such hostility? Sawhney traces the rise of the animosity instigated between the Jats and Muslim communities, and how it was used as a political tool to gain power. ‘Love Jihad’, fake videos being circulated, communal hate songs, changing of district/city names, growing suspicions – an agenda of creating division is clear and scarily familiar by right-wing radical groups. We see the true faces of India’s ‘angry young men’ shouting slogans, fear-mongering, with a weapon in hand.

On one hand, we clearly see the roles played by the BJP, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad and Bajrang Dal and on the other, the absolute lack of action by the ruling party at the time, the Samajwadi Party. Could the violence have been nipped in the bud?

Muzaffarnagar may have been a stepping stone into political power for some, but the impact that the violence has had across the country has made it a blood-stained unforgettable moment in Indian history. It was another notch, a significant one, in the cycle of hate and fear. But when such misinformation and divisiveness is being perpetuated, there is always resistance, one that has been growing over the years from 2013 till today. We see this in the film in the form of activists and the Naujawan Bharat Sabha’s on-ground work.

Muzaffarnagar Baaqi Hai is an important documentary that raises uncomfortable questions for everyone involved, and it’s understandable why so many right-wing groups protested the screening of this documentary. It makes you realise just how easy is it to divide us as a society, how grossly mismanaged government relief is. What do you do when the state government looks the other way? Where were the other political parties when all of this were was happening, why didn’t they step in? How far are we as humans willing to go to gain power?

Divide and rule is perhaps the Britishers greatest legacy left behind in our country, a power play that continues to be used. In the game of political chess, the pawns are often the weak and disenfranchised, who here, in Muzaffarnagar, were once neighbours and friends ultimately pitted against each other. The 2014 elections came and went – the result was what the BJP worked hard to achieve, but what then, in the aftermath of the campaigning and rallies do the people gain?

You can’t help the flurry of emotions that course through you as the end credits roll. It’s an up-close and personal look at a world that many of us, me sitting here behind a screen, have been long shielded from and the news cycle dropped off their radars – well, until now perhaps, with the Delhi High Court’s verdict convicting Sajjan Kumar in the 1984 anti-Sikh riots, bringing Muzaffarnagar back into the limelight, so to speak. Watching Muzaffarnagar Baaqi Hai is an overwhelming experience that every one of us needs to undertake. The footage is all there – videos of the inflammatory, polarising speeches being given by leaders of different communities and parties, of the men accused as instigators being felicitated by the political party in front of a rally. Unfortunately, it is only the ones privileged enough to have a Netflix subscription, like me, that have gotten a chance to view it in its entirety. Maybe it’s a good start, for us urban-dwellers to wake up and step out of our bubbles.

You can watch the documentary online on Netflix.

If you liked this article we suggest you read: