- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

“Haaye beta, tumhara rang itna saaf tha jab tum choti thi [your skin was so much lighter when you were younger]” - raise your hand if you’ve ever had this gem thrown at you, following a dramatic sigh and a click of the tongue. Raise your other hand if you weren’t allowed to play outside when it was sunny to avoid getting ‘dark,’ or spent your time after school getting haldi and besan rubbed on your arms, face and legs in a bid to make you fairer.

Prejudice against darker-skinned people, especially women, is not a new phenomenon but one that has been deeply rooted in our culture, be it due to some sort of colonial hangover that has loomed over our society for hundred of years now, or as some reports state it to be tracing back to the caste system where members of the lower caste often had darker skin. Young girls growing up and being told that having fair skin determines the quality of their life distorts their sense of self and ingrains what’s basically racism and colourism at a psychological level.

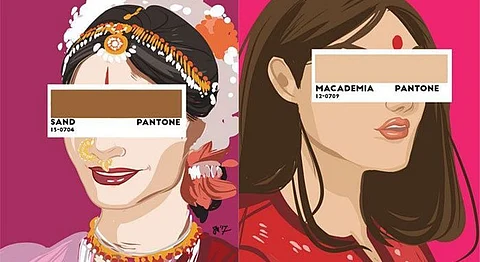

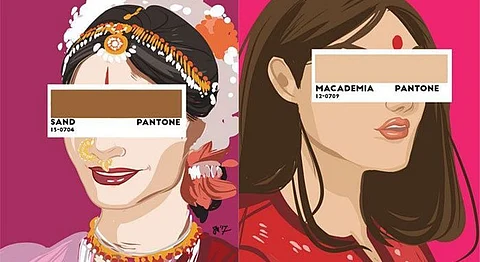

Anoushka Agrawal was one of these young girls. Now a 17-year-old high school student, she turns to art as a creative outlet. Her relationship with her dark complexion has been a complex one, much like the rest of society. As a child, she couldn’t understand the need for people to point it out - why was it even a matter of discussion? “As I grew older, I began to dislike my dark skin increasingly, because it started to become my weakness - the reason I was teased at school, the reason I felt unattractive,” she tells Homegrown. Her turning point came when she was in the eighth grade, a particular incident that she says in the first post of Shade Card, a six-part art and poetry project collaborated on with artist Tara Anand. These six short-style poems are based on true stories of their peers, all who have been faced colorism in their lives. “We’ve called it shade card in reference to ‘the woman card’ or ‘the race card’ where complex inequalities are reduced to make it seem like people taking advantage of their identity. The title also is an allusion to the pantone shade cards that play an important role in the visuals,” explains Tara.

“This incident [the first Shade Card] made me understand just how much importance Indian society gives to complexion. Complexion in India, as well as in many parts of the world, isn’t merely the colour of your skin. Here, it represents your socio-economic standing, your intelligence, your talents, and your flaws. I began to realise how ridiculous the correlation of complexion to other, completely unrelated, aspects of life really were, especially in a country whose people are collectively termed as being ‘brown’ by the rest of the world. I decided to embrace the identity I was running so far away from, and began to turn the conversations about complexion that I was a part of into making those around me understand what colorism really is, and why it shouldn’t be as prevalent in Indian society as it currently is. Shade Card attempts to do just this - to make people aware of colorism and how deeply embedded it is in our lives,” says Anoushka.

Art is often discussed as being a medium of discussion, especially for topics that we rarely talk about. For Tara, it has the strange ability to appeal to its audience, entertain them, and still engage them in uncomfortable discussion. “Some of the most effective pieces of social commentary have been pieces of pop culture, engaging their audience and making them more sympathetic to the more uncomfortable message or topic,” she comments. “When anoushka pitched it to me, she emphasised that she wanted to cover people of various skin tones so from the beginning I was picturing them placed in from dark to light the way you would place colours on a pantone colour chart. That’s what put the idea of the pantone colours in my head. I decided to use it because I’d never thought of complexion as just colour and thinking of it that way made it seem so silly to assign so much importance to it. I wanted people to look at the pantone cards and think ‘oh! this is like what I use to pick colours for my walls or furniture!’ so that they’d see how strange it was to load colour with so much social significance.

As a Bharatanatyam dancer, Anoushka’s ‘remedy’ for having darker skin tone was always through the use of makeup, though she no longer hides. “To a young girl being teased about her complexion - don’t think of it as a weakness, because it isn’t. Laugh the ridiculous comments off, because your olive, tan, chocolate or even pale skin doesn’t determine your success. Find what you love doing and keep doing it, and show people that your complexion wasn’t the slightest barrier to the incredible woman you will become,” she says, and we couldn’t agree more.

Their aim seems to be being achieved as the reception they receive is encouraging, but also tinged with a pleasant surprise at the subject matter. As Tara tells us, people have identified with the stories, and after seeing viewing the entire series - art and stories, it’s understandable why they’ve struck a chord.

“We hope that Shade Card would aid in this understanding of colorism and bring to light how much unnecessary importance we really give to complexion,” the duo signs off. We’ve posted Anoushka and Tara’s series below with their permission.

Tired but happy, she took a sip out of her water bottle

And stepped out of her car. She walked to the lift of her building, her little

Earrings dangling from her ears as sweat dangled from the apex of her chin.

She had a big performance the following week, because of which her shin

Had begun to ache with the long hours of rehearsal, but she didn’t mind.

Her Indian classical dance form allowed her to leap, to fly, to find

Within her the beauty that she had for years not been able to trust.

When she danced, she transcended universes; reality turned to dust.

She straightened her kurta, wiped the moist off her cheek with her sleeve,

She shook the bag on her shoulder, to make sure she didn’t leave

Her ghunghrus behind. She stopped before the four lifts of her building’s lobby, smiling at the watchman

Who didn’t smile back. The doors of the lift opened; she entered and suddenly stopped, deadpan

When she heard the lady next to her speak. The lady was older, bigger, and had tremendously heavy make-up on;

She adjusted her ridiculously shimmery sari and looked at the object of scorn

In front of her, at the representative of the category of people that was inferior to her own. “Whose house do you work as the maid in?”

For a minute, the girl stared at her, confused. Then, glancing at her dark skin,

She understood the lady’s question. Not knowing what to say,

She mumbled something about her dance class, then quickly made her way

Out of the lift as soon as the doors opened. She felt a strange disconnection

To her own self. Never before had she been more conscious of her complexion.

‘You’re caught!’ the girl threw her head back and laughed, her eyes small with delight

As she pulled her friend, the thief, into the jail. She could never lose, not without a fight.

Her friend rolled his eyes and giggled, retiring to the ground

As she ran out again, to catch the other thieves who were waiting to be found.

She scanned the back of every pillar, inspected the space below every chair,

She flew through the hallways, ran up flight after flight of stairs.

One by one, she caught all the speedy, conniving thieves, returning

To the jail triumphant each time. Her stomach churning

With delight, she declared the winning group. ‘The police have won!’

The rest of the police force high-fived one another, the sun

Making their wide eyes reflect every ray that hit them. They

Picked up their water bottles as the school bell yelled, calling to midday.

‘We won’t call her to play with us tomorrow,’ one of the boys said, as they scampered back to class,

‘I’m telling you, she cheats. How else can she be that fast?

‘Plus,’ he added, in a patronizing tone,

‘She’s too dark.’ The girl stopped and stayed right where she was, alone.

Her pride faded away, dripping through her dusky skin,

She didn’t want to fight anymore, she didn’t want to win.

She threw herself onto the ground and buried her head in her hands,

She looked at her skin, confused. She didn’t understand

Why her complexion mattered to them. Without another word,

She slumped back into her seat, dejected, discouraged, unstirred.

Historic train stations, art galleries, beaches that stretched for a thousand miles.

She loved everything about her city — its crowd, its chaos, the warm smiles

She was greeted with each time she entered her favorite café. She loved its

people –

She loved how liberated they were; fearless, friendly, always in a hurry and still

So alive. She hailed a taxi, stepped in, and was about to become one with the blur

Of trucks and cars and motorbikes on the street, when a voice stirred

Her back into reality. “Are you from Bombay?” the taxi driver asked,

Looking at the girl through the rearview mirror; the bottom half of his dark face

masked

With a thick moustache. The girl nodded yes, before adding, “But originally, I’m

from South India.”

The driver’s eyes widened as he tore them away from the road to look at her. As

the car

Slowed down in front of a traffic signal, he continued, “I am from the South as

well,

But I can’t believe you are too! I definitely couldn’t tell;

With your light complexion, I assumed you’re from the North or the West of

India. It’s good

That you don’t look like you’re from the South! You should

Be happy,” The driver said, touching his face as he looked at his own reflection in

the rearview mirror,

And sighing. Confused, the girl turned her

Face back towards the window, and watched her city speed by.

Her city, with its palm trees and bright lights. The Mumbai

That allowed all voices to be heard, big or small. The Mumbai that was an

amalgamation of all things Indian;

That allowed all voices to be heard; made every opinion

Matter. The city that brought together cultures from every corner of the country,

The city that was supposed to accept all religions, all ethnicities, all kinds of

people. The city that didn’t discriminate; the city that was happy.

She sat in front of the mirror in her button-down shirt, the table in front of her

Covered with hairpins, flower rings, jewelry, a pair of scissors

And bottles and bottles of peach-colored make-up. She closed her eyes as her face

Changed shades, getting lighter and lighter with every base.

Her eyes stung as they were painted darker to stand out against the fairness, and a tear ran down

Her cheek. ‘Don’t worry’, the make-up artist sighed, applying yet another round

Of foundation. The girl had everything she needed for her performance –

Her costume, her choreography, her concentration, her confidence.

That’s all she needed, didn’t she?

She slid her bangles onto her wrist, three

On each arm, and tightened the gold belt on her hip.

She was getting late;

She packed her bag and was about to leave when, a loud, ‘Wait!’

The make-up artist walked towards her with a peach-coloured sponge and

Covered her arms with the colour; from her shoulders down to the tips of her hands.

He looked at the girl and smiled. “Now, you’re ready.” As the girl walked out, she contemplated

How much the world had changed from when her dance form was first created.

It didn’t matter that she was to depict Lord Shiva in her performance that day;

Shiva, whose skin was dark as night. It didn’t matter that she was going to portray

Goddess Kali — again dark-skinned, fierce and powerful. No –

In the final performance, regardless of the perspective a dancer wishes to show,

Regardless of the statement she tries to make, regardless of the story in her art,

She is made fairer; ‘prettier’, such that it is impossible to tell her apart

From the others. It didn’t matter that she wanted to use her dance to empower,

To change the narrative, to tell stories from the nooks of reality; to flower.

With all the modernity around her, she was still a dark girl who took hours

To become lighter; to ‘look’ like a classical dancer. She wished she had the power

To bring a little change — to bring the contemporary

Into a traditional dance form, and a seemingly traditional society.

She tilted her head. The fish swam right and left, up and down; in all directions.

It was as if they were creating and breaking patterns; always making corrections

To the art they seemed to be producing with their fins. She wished she had fins,

too.

She wished she had a tail, she wished she has scales, she wished she was painted

a hundred different hues

Just like the fish. She tore her eyes away from the tank and ran into her

bathroom

As fast as her 7-year old feet could take her. She ran out in her blue flippers and

her pink bathing suit; one could only assume

That she adored the sport. She put on her lemon-green cap and her red

Goggles, and, standing in front of her mirror, she fitted them on her head.

Within seconds, she was out her door and inside the swimming pool of her

residential building.

She suddenly couldn’t tell what she was doing anymore. She didn’t know if she

was sprinting,

Dancing, or flying. She didn’t know which world she was in; it couldn’t have been

the real one.

She felt like just like the swordtails in the fish tank. She wanted to scream, run,

Jump and merely float, all at the same time. The water made her powerful.

Suddenly, she felt a tug. She felt someone pullHer to the surface of the pool. “What are you doing?” Her grandmother asked,

angry.

“You cannot swim now! It is summer, do you not see

The scorching sun? You will get terribly tan,” she continued, persuading the girl

Out of the pool; out of her comfortable, peaceful swirl

Of happy and into the safe shade of her apartment. The girl ran

Into her room, furious. All she wanted to do was swim. She didn’t see anything

remotely wrong with a tan.

She laid out her brand-new lehenga on her bed, admiring it.

She didn’t mind how expensive it was, or that its fit

Wasn’t the best. She thought it was beautiful; she thought its bright

Yellow color made her seem happier than usual. She stood in front of the lights

Of her bedroom mirror, put the lehenga on, and was, within minutes, out of her house

And on her way to her friend’s Diwali party. She adjusted her blue blouse

Before entering the venue. Diwali was her most favorite festival; she adored the sparkling fireworks

And the glimmering lamps; the exquisite food and all its other quirks.

She rang the doorbell and greeted her friend with an embrace.

She wasn’t surprised to see many strangers at the party; her friend was a popular face

In every social circle there was. She was in conversation with a group when an unfamiliar man

Joined in. After introducing themselves to one another, they began

Talking about the history of the festival; the man didn’t know

Enough about its reasons for celebration. The girl felt her excitement grow –

It was common knowledge that she knew absolutely everything about Hindu mythology.

She knew everything about the Ramayana — the tale of the origins of Diwali — right from its chronology

To its most intimate details. When the man turned to her and said,

“You must be more uninformed than me about this!” she jerked her head

Back in surprise. Offended, she asked, “Why so?”

“Well, your white skin must mean you aren’t from the country, so you wouldn’t know

Enough about its culture, would you?” She shook her head, appalled. She

Didn’t realize that her complexion could strip her off her culture completely.