- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

One morning in May 1873, a grisly murder shook colonial Bengal and triggered a media and cultural frenzy that rippled through Calcutta's courts, newspapers, bazaars, and artists' studios. At the heart of the scandal was a young woman named Elokeshi, killed by her husband Nabin Chandra Banerjee in a fit of moral outrage after she allegedly confessed to a sexual relationship with a Hindu priest. But what might have remained a tragic case of domestic crime in another context became a sensational murder trial that exposed deep societal anxieties and tensions between gender, religion, colonial law, and the emerging modern middle class in 19th-century Calcuttan society.

An Affair... Or An Assault?

The story goes like this: in the summer of 1873, Nabin Chandra Banerjee — a westernised young government clerk from Kashipur — accompanied his wife Elokeshi on a pilgrimage to Tarakeshwar: a sacred city on the bank of the Hooghly river named after its patron deity, the Hindu god Shiva. Desperate for a child, the young couple had decided to visit the Taraknath Temple, hoping for a divine intervention to cure their infertility. Here, they met the holy mahant, or high priest of the temple, Madhavchandra Giri, who took Elokeshi — then only sixteen — under his wing and promised her a son.

This is where the story took a tragic turn. Almost exactly a year after the visit, in the summer of the following year, on 27 May 1873, Nabin beheaded Elokeshi with a boti — a traditional curved Bengali fish knife — at her ancestral home in Kurmul, around 70 kilometres from Kolkata, and surrendered to the local police. According to 19th-century police records and archival newspaper retellings of the event, Elokeshi had allegedly told Nabin that she had had sex with the mahant, likely in order to conceive a child. We'll never know whether it was a consensual extramarital affair, or an assault against the teenage woman, but what we do know is this: after listening to his wife's confession, the distraught Nabin, picked up a nearby boti and slit her throat in a fit of moral outrage in the heat of the moment.

A Sensational Murder Trial

What followed was a sensational murder trial that captured the popular imagination of colonial Bengal and exploded into one of colonial India's first true crime sensations. At the murder trial, which took place in the Hooghly Sessions Court at Serampore, famous Bengali barrister Umesh Chandra Bannerjee (Womesh Chunder Bonnerjee), one of the founding members and the first president of the Indian National Congress, chose to represent Nabin pro bono and argued that the young husband had the right to 'uphold' his honour. In a concurrent second trial, Madhavchandra Giri too was held accountable for adultery, which was a civil offence in England, but a criminal offence in British India.

The courtroom quickly became secondary to the public spectacle that unfolded around the Elokeshi murder case. Newspapers in both English and Bengali reported every detail, and the Bengali middle class society largely sided with Nabin, whose sympathisers framed him as a wronged husband defending his honour in the face of religious corruption. The mahant, for his part, represented a figure of both sexual deviance and unchecked power, unsettling even the colonial state.

While Nabin was found guilty, he received a relatively lenient sentence of 12 years' exile to the Andaman Islands. The mahant, too, convicted of adultery, was sentenced to rigorous imprisonment of 3 years in the Presidency Jail in Calcutta.

A 19th-Century Pop Culture Phenomenon

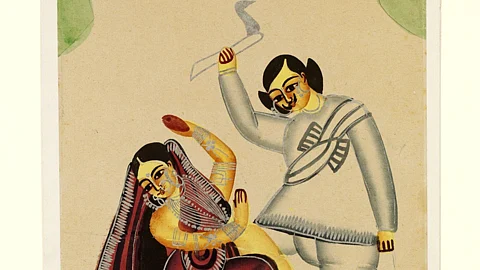

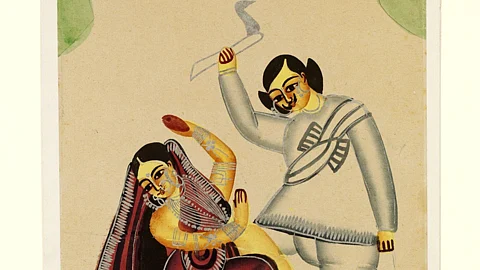

The Elokeshi murder case soon became a visual and narrative obsession in colonial Calcutta's popular culture. Artists of the Kalighat Pat tradition quickly seized upon the case. Their depictions of the case ranged from images of Elokeshi as a demure victim; the mahant as a lascivious, corpulent villain; and Nabin as a man tormented by betrayal. These pat paintings were graphic, dramatic, and unapologetically moralistic. Some even showed Elokeshi's severed head, while others the moment of her confession, and still others imagined the priest's seduction as a grotesque tableau.

Although often dismissed by the colonial elite as a vulgar or unsophisticated vernacular art form made for tourists and the masses, Kalighat Pat paintings were often a barometer of public sentiment and anxiety. These paintings both illustrated and interpreted the case, assigning blame, amplifying outrage, and reinforcing social codes. The moral didacticism of these images suggests how ordinary Bengalis grappled with emerging tensions: the sanctity of marriage, the vulnerability of women, the abuse of religious power, and the legitimacy of vengeance.

At the same time, the Elokeshi murder case also reveals how colonial modernity in Bengal was increasingly shaped by the spectacle of scandal. Just as the Victorian public devoured stories of passion and punishment in England's penny dreadfuls, the nouveau riche Bengali middle class bhadralok society participated in a homegrown culture of sensationalism through newspapers, public debates, and cheap art prints. Elokeshi, in death, became both a cautionary tale and a folk martyr.

A Colonial Crime & Its Contemporary Echoes

Elokeshi's murder existed at the intersection of intimate partner violence, moral policing, and societal complicity. 150 years later, its circumstances remain disturbingly familiar. Just as Elokeshi's death was framed as a consequence of dishonour rather than a crime against her autonomy, many contemporary cases of gender-based violence in South Asia are still justified through the language of shame, provocation, or familial honour. The sympathy extended to Nabin, Elokeshi's husband and killer by colonial courts and public opinion mirrors ongoing failures in how justice systems in India, and across the world, respond to domestic violence. Her story forces us to confront crimes against women not only as a historical tragedy, but within the context of present and persistent normalisation of violence against women within private spaces, and the cultural narratives that excuse it.