- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

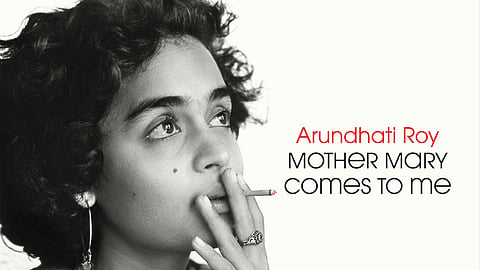

Arundhati Roy’s Mother Mary Comes to Me reads like a needle passing through tough cloth — piercing, drawing thread, knotting, reopening. She names an intimate grammar for how many Indian women are made and remade — or as she puts it: “destroyed and stitched back together”. Roy’s memoir shows us a double bind: to be a daughter is to be asked for silence in the name of gratitude; to be a mother is to be sanctified into divinity and, in that sanctification, denied fallibility. Between these stretch the tiny, daily negotiations that make a life.

India venerates 'Maa': the self-sacrificing one whose virtue is measured by how much of herself she surrenders. That figure commands reverence in cinema, advertising, political speeches, and family conversation. Yet sanctity is a trap disguised as a garland. When motherhood is divinised, ordinary human texture can't be admitted without scandal. The result is paradoxical: mothers are burdened with impossible perfection, and daughters are burdened with the duty of eternal gratitude to uphold that perfection.

Roy refuses both pieties. She records a mother who is audaciously public-spirited and also imperious at home; who wins a landmark inheritance case expanding daughters’ rights and also punishes her children for years. Mothers needn't be divine to be worthy. Indeed, insisting on their divinity is a sly way of denying them the right to be human.

The subtlest violence in familial India is often committed in the dialect of care. Tenderness can be weaponised into technique; shelter can turn storm without warning. Many daughters know this choreography — the “for your own good” that polices ambition. A mother’s reputation for saintliness can drown out a daughter’s account of injury. The culture supplies the chorus: "How dare you speak plainly about the one who gave you life?"

The fear of being read as ungrateful is the social glue that binds daughters into compliance. It's also the solvent that erodes their capacity for speech. Roy risks the charge of ingratitude to make a larger argument about power. In doing so she gives many of us a vocabulary long withheld: the right to describe love that did not always feel safe.

Indian public life admires defiance in women on the condition that it's ideologically convenient. Outside the home, a 'fighter' is lionised — teacher, activist, headmistress, judge — until she insists on equal dignity inside it. Then she becomes 'difficult'. Roy’s mother is, in many tellings including her own, formidable: she builds a school, confronts a church-backed legal order, dares authority on stage and in court. The same steel, turned inward to govern children, becomes oppressive. Female power is admirable only when it serves others and leaves no bruise.

Her mother’s public victories and private abrasions are shown together, not to collapse one into the other, but to show that the human being who accomplished the first also committed the second. Our reverence for the 'Maa' archetype often disfigures actual mothers. It forbids them error, denies them repair, and equips them poorly for intimacy.

Roy connects the micro-politics of her childhood with the macro-politics of the Republic. The memoir’s recurrent feeling mirrors the experience of citizenship under a nation-state that demands love while making dissent perilous. The daughter who learns to anticipate the weather in a mercurial household grows up to read the barometer of a mercurial polity. The line between 'home' and 'homeland' blurs. To be punished for speaking out in either sphere is to understand how sentimental stories mask arrangements of power.

How do we love a home, a mother, a country that sometimes harms us? The answer the book proposes is harsh and hopeful: by refusing the sentimental lie, by speaking plainly, by staying when we can, and by leaving when we must.

A culture that worships the self-sacrificing mother breeds daughters who learn to apologise for inconvenient truths. Roy cuts through the sentimental thicket with a machete of plain speech. Love and deference are not synonyms. To love a mother is to grant her complexity. To love as a daughter is to abandon the performance of piety and practise the work of relation. To love as a mother is to relinquish divinity and practise accountability.

What intimacy might be possible if we retired the 'Mother-Goddess' and the 'Good Daughter'? The task is not to choose between loyalty and truth but to practise a loyalty that tells the truth. Mothers need not be divine to be worthy. Daughters need not be dutiful to be loving.