- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

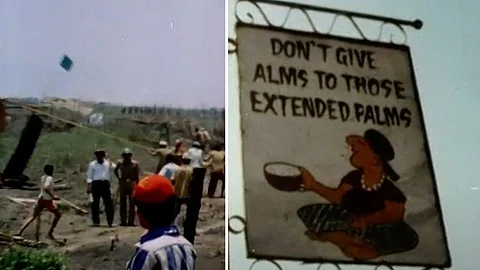

Hamara Shahar (Bombay: Our City), opens on the 1983-84 Yearbook of the Greater Bombay Municipal Corporation — with proudly presented images of ‘A Neatly Divided Street In Chembur’, ‘Smooth Flow Of Traffic at Wadala Flyover’, and ‘Mahalaxmi Race Course In Action’. Hamara Shahar is a documentary about the slum dwellers of Mumbai, when it was Bombay, and is a testament to the fact that Bombay is a dichotomy like few others.

In one scene we see a Municipality Commissioner in his bungalow, a well-watered lawn, answering some questions. “We have had to demolish the huts to keep this land clean of trespassers," he says. "We want to have control over the number of people migrating to Bombay from other places. It has been decided that only those people who came here before 1968 will be given housing facilities. It is important to let anyone else know that street dwelling and staying on footpaths will be condemned.” In a later scene, we see people scrambling for any documents that prove their migration to Bombay before 1968 using hospital bills, work invoices, and death certificates.

With water, electricity, and other amenities being scarce if the dwellers are lucky, a budding politician says, “I am quite saddened by this water problem. Everytime I think about it, tears drip down my cheeks.” He later does win an election; a ray of hope for the people of 'Jhopadpattis' or slums.

In another scene, the Municipality Commissioner tells the interviewer that it’s difficult to trace where the dispossessed people live after their slum dwellings have been demolished. “It’s better they go back to where they came from,” he says.

This line confused me, and the interviewer too apparently, who asks him to explain. “They must’ve come here from somewhere," he says. "They should go back there. There’s no question of giving them any alternative accommodation.”

Even the free school built by social workers in the slums for the children there has been demolished. “Despite having the Collector’s permission,” says the teacher at the school, “police Officers have come in and demolished this school. Their excuse being that they assumed this was a garage.” The school was rebuilt, but no one knows how long it will remain. The right to education, along with their homes, families and belongings have been stolen.

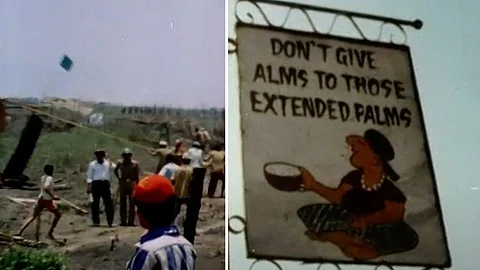

There’s a scene in the documentary where an upper-class woman, dressed in plaids and pearls says that Mumbai looked much better in the 1920s without the migrants and slum dwellers. “It’s embarrassing when we have visitors who question us about the stench that comes from these slums”, she says. Patwardhan so cleverly cuts back to images from the 1920s where Britishers are in carriages pulled by Indians, and Indian sweepers and cleaners, with Tchaikovsky’s ‘The Nutcracker Suite, Op 71a’ playing ironically in the background.

40 years after its release, corruption and economic class divides remain even wider. The slum population has increased by over a million since 1984. The last census in 2011, lists a number of 5.2 million slum dwellers in the Greater Mumbai Corporation Area. The Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation, also decided to impose a property tax on all commercial establishments in slum areas earlier this year, but stated that the imposition of the tax will not legalise the unauthorised structures, which incidentally is also a great moment for Tchaikovsky’s ‘The Nutcracker Suite, Op 71a’.

Hamara Shahar remains one of the truest representations of Bombay, and Mr. Patwardhan, the difficult-truth-teller of India, for this film does exactly what art is supposed to do; comfort the disturbed and disturb the comforted.