- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

A film is an event, an artifact, an argument. The Untitled Kartik Krishnan Project (2010) is a confrontation — with the rigid structures of Indian cinema, with the aesthetic constraints of budgetary necessity, with the metaphysical nature of storytelling itself. In its making, in its viewing, it demands a reconsideration of what cinema can be.

There is a prevailing myth that cinema is bound to premeditation — that a film is best when it is meticulously planned, its movements and moments charted in advance. TUKKP upends this assumption. Its structure is porous, its dialogue unfixed, its very being is fluid. The film is a living organism, adapting to its surroundings, assimilating the constraints imposed upon it. The absence of a strict script, the use of locations found rather than fabricated, the presence of unknown extras — these are fundamental to its aesthetic. In allowing improvisation to dictate it, TUKKP becomes a radical experiment in cinematic truth.

To create with limited means is an act of defiance. The film’s production was executed in fragments over the course of a year. Locations were transient, access was limited, and at one point, the protagonist’s primary setting — his home — physically collapsed. These interruptions did not derail the film but rather confirmed its necessity. TUKKP is an insistence that cinema can emerge from the cracks of the everyday. What is most radical is its refusal to conceal its conditions of creation. Traditional cinema seeks to suppress evidence of its own making, aspiring to the illusion of seamlessness. But TUKKP makes its limitations visible. The film itself is a record of its own struggle to exist.

There is a double movement in TUKKP: it is both a film and a film-about-filmmaking. Kartik Krishnan’s quest to make a short film mirrors the film’s own process of coming into being. This is a confrontation with the ontology of cinema. To make a film is to engage with the contradictions of time and space, with the fickleness of reality, with the limits of control. TUKKP enacts this.

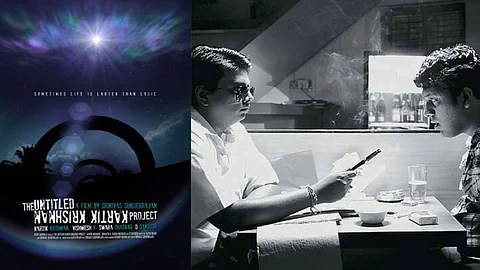

If all cinema is, in some sense, a meditation on time, then TUKKP pushes this meditation to its logical extreme. What began as one film became another, its narrative and form shifting in response to life. The film, then, is both document and fiction, both planned and accidental. To watch TUKKP is to encounter a form of resistance. It resists conventional narrative closure. It resists high production values. It resists the distinction between the polished and the rough, between the professional and the amateur. The use of black-and-white, the reliance on long takes, the absence of elaborate mise-en-scène — these are choices that assert a different cinematic ethic. This is a film uninterested in spectacle, uninterested in appeasement. It doesn't attempt to seduce you.

TUKKP interrogates the world of cinema. In doing so, it demands that we, as viewers, shift our expectations of what cinema should be. It invites us to recognise that cinema is not simply about what is represented but about the act of representation itself. It calls attention to the conditions of its making, forcing us to ask: How do you create with nothing?

Cinema, in its most radical form, should unsettle. The Untitled Kartik Krishnan Project doesn't offer easy answers, nor does it seek to conform. Many films are independent, but this one is an argument for a new way of seeing.