- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

On view at Vadehra Art Gallery until January 24, Ashfika Rahman’s ‘Of Land, River, and Body (Mati, Nodi, Deho)’ marks the Bangladeshi multi-disciplinary artist’s first solo exhibition in India. Bringing together three interconnected projects, the exhibition weaves photography, textile, sound, and installation into an intimate archive of displacement, climate violence, and state repression — where land bears witness, rivers speak, and survival itself becomes an act of protest.

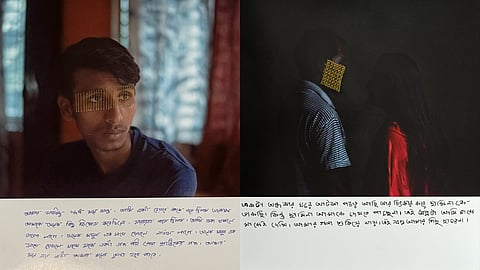

Bangladeshi multi-disciplinary artist Ashfika Rahman’s ‘Of Land, River, and Body (Mati, Nodi, Deho)’ — on view at Vadehra Art Gallery, New Delhi, until January 24 — marks the 2024 Future Generation Art Prize winner’s first solo exhibition in India and a powerful reflection on power, memory, and survival in South Asia. Featuring three interconnected ongoing bodies of work — 'Than Para: No Land Without Us', 'Files of the Disappeared, and 'Behula These Days' — the exhibition creates an immersive archive of lives shaped by dispossession, erasure, and fear. “Influenced by my mother’s work as a social worker, this exhibition revisits marginalized communities and the systemic suppression they face, re-archiving voices long unseen and unheard,” Rahman explains.

Rahman’s multi-disciplinary practice moves deliberately between art and documentary, but resists the cold distance often associated with either mode. Working across photography, textile, sound, text, video, and installation, she builds what might best be characterised as an ethics of proximity. Her works do not simply represent marginalised and indigenous communities in Bangladesh; they are shaped through sustained collaboration with them. Through embroidered portraits, stitched letters, and everyday objects like temple bells, Rahman comments on the tactile residue of lived experience — of collective care, grief, and resistance — embedded into their very materiality.

‘Of Land, River, and Body’ brings together three interlinked projects, 'Than Para: No Land Without Us', 'Behula These Days', and 'Files of the Disappeared', shaped through collaboration, resistance, and remembrance. Working with communities affected by displacement, violence, and silence, the projects transform pain into testimony. Bells touched by villagers, letters embroidered by riverine women, and portraits stitched with gold thread form an intimate archive built on care and solidarity. Here, land bears witness, the river speaks, and the body records resistance. Together, the works affirm art as a space where erased histories persist and where survival itself becomes an act of protest.

Ashfika Rahman

In 'Than Para', Rahman confronts the violent realities of land-grabbing and forced displacement in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. Rather than offering a distant overview of structural injustice, she focuses on how land is experienced as intimacy: something held, cultivated, and remembered. The village becomes not just a site of loss but of testimony, where the act of remaining itself is political.

'Files of the Disappeared' turns to judicial violence and custodial torture, documenting the experiences of individuals arbitrarily detained by police prior to Bangladesh’s recent political upheavals that unseated long-time incumbent Sheikh Hasina’s Awami League government in August 2024. Developed in consultation with psycho-social counsellors, the project is careful not to sensationalise trauma. Instead, Rahman foregrounds absence — missing bodies and silenced voices — as evidence of state power. The work insists on presence precisely where official records refuse it.

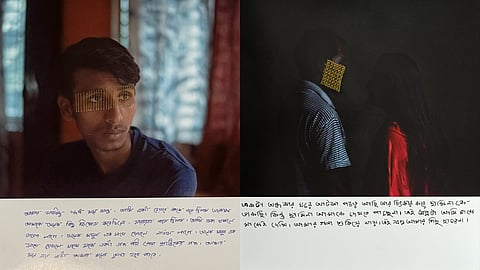

Perhaps the exhibition’s most haunting body of work, 'Behula These Days', draws from the Bengali folkloric figure of Behula to examine the gendered nature of climate violence along flood-prone riverbanks in Bangladesh and eastern India. Here, rising waters have become existential threats disproportionately borne by women’s bodies. By weaving folklore into contemporary documentary, Rahman collapses temporal distance, reframing mythology as not only an escape but a language through which vulnerable communities articulate their precarious presence.

As Dr. Melia Belli Bose, Associate Professor of Asian Art at the University of Victoria, Canada, notes in her curatorial essay for the exhibition, Rahman’s work recalls Roland Barthes’s assertion that every photograph is a “certificate of presence”. Yet Rahman extends this logic beyond photography. In her hands, textiles, sounds, and installations also become certificates — proof that someone was here; that something happened; that erasure has limits.

Ultimately, ‘Of Land, River, and Body’ is less about witnessing suffering than about insisting on dignity. Rahman’s work becomes an active space where suppressed histories persist and where survival itself is framed as a form of protest.

If you enjoyed reading this, here’s more from Homegrown:

"What Does It Mean To Survive A Fractured World?" Asks An Upcoming Kochi Exhibition

Sneha Nayak's 'Ornamental Grids' Are An Antidote To Global Design's Post-Colonial Hangover

150 Years of Plunder: Devadeep Gupta’s Art At The Edge Of A Ravaged Assam Rainforest