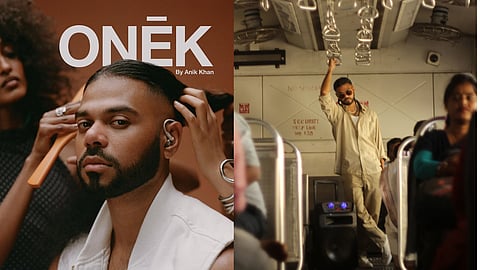

ONĒK's Awakening: How The Bangladeshi-Queens Rapper Learned To Love Himself

A Homegrown interview with Bangladeshi-American rapper ONĒK where we dive into his artistry as well as his heritage as a third-culture creative.

There’s a lot more to Anik Khan, aka ONĒK, than immediately meets the eye. Beneath his effortless charm, his million-dollar smile, and his easy-going, amiable personality is a heritage, a story, an intensity, and an unwavering vision and attention to detail. It’s all of this that has fundamentally buoyed his career over the course of the last decade. To call him an R&B and hip-hop artist is to barely scratch the surface of his past and the future that he’s aiming to shape for himself as a creative.

Born to Bangladeshi immigrant parents, the Queens-based singer and rapper has carved a path that’s been shaped by his multicultural upbringing. His latest self-titled album is the culmination of both artistic and personal self-discovery. It places Anik right at the centre of a growing vanguard of South Asian diasporic artists who are using their roots to elevate and evolve genres that haven’t always seen them take up positions of prominence.

From the introspective playfulness of songs like ‘Spoiled Brown Men’ to the angst-filled defiance of songs like Over // Under, this album is a reflection of a South Asian artist who’s drawing on the full measure of his hybridity and his multiculturalism to create music that refuses to be defined by any singular label. It’s super slick, modern production and samples are regularly offset by an almost retro approach to incorporating South Asian instruments and motifs. It takes everything we love about modern hip-hop, R&B, pop, and electronic music and seamlessly blends it with the music of the subcontinent. The results are soundscapes that come directly from the mind of someone who’s had to deal with the adversity of being ‘othered’, but has nonetheless come out smiling and thriving.

Across the length of the self-titled effort, there are moments of poignancy and reflection, but it never lingers too long on darkness. Instead, it chooses to embrace the warmth and light of the diasporic experience and pay tribute to the families, identities, and sounds that have forged a path forward for South Asians and Bangladeshi’s across the world. Anik deliberately chooses celebration over rumination; a smile over a grimace and grit of the teeth. As Idles put it on their iconic 2018 album, it’s fundamentally “joy as an act of resistance.”

We sat down with Anik recently to learn more about the making of ‘ONĒK’ and the evolution of his multifaceted artistry.

What’s your elevator pitch for your own artistry? What do you love the most about what you do as an artist? Is it about connection, discovery, performance or something more? When did you decide you wanted to make music your life, and what’s the journey been like so far?

I’m ONĒK, I’m a Bangladeshi-Queensborough thoroughbred, and my music is all about tradition meeting tomorrow.

What I love the most about what I do is being able to create. Creation is what keeps me going. It’s my curiosity and my will to want to continue to blend genres and discover different things about different places in the world. To have that influence on my music, it’s just something that I will always have. Queens has over 138 languages spoken in one borough. It's the most diverse place in the entire world, and for me, being able to continue to listen to different genres and different types of music and seeing how I can blend it and make it my own is what keeps me excited.

There’s always a lot of pressure for South Asian artists to sound a certain way or to conform to a certain stereotype within Western music. How do you strike that balance between making music that’s authentic to your identity and that speaks your truth while avoiding the unfair comparisons that come with being a brown man in America?

We don't have enough. People here often make unfair comparisons, which is so unfortunate. I don't even have anyone where they could be like, “Yo, you know what? You sound like so and so, or whatever.” Because so far we have only had hit singles happen, right? Because there hasn't been really a face or an ideal brand for an Indian artist in the west.

We're not like London, where South Asian heritage is celebrated a little more. We’re still very much trying. There are way more South Asians making a name for themselves in America now, including myself. You can see the movement starting to happen, but we need someone to take it to the next level. We don't have our Shakira or our Rihanna yet.

When we think about the South Asian conversation, we often think about it from a lens of India and Pakistan and I don't mind saying that. In no way am I saying I don't like India or Pakistan. They're great. I make music with these people, and I think the things they have done are incredible. Punjabi music is my favourite genre in South Asian music, so I understand why it's doing so well. But there are nuances, and although we do overlap, we all also have our niche differences. And I think those niche differences are something to celebrate, right?

Can you talk a little about this current moment in time for South Asians? We’ve just seen a South Asian muslim elected as New York City mayor. What do you think has changed and shattered that proverbial glass ceiling for South Asian artists? What are some of the biggest obstacles that you think continue to hold the community back? What could we be doing better to elevate our own diverse cultural heritages within the hybrid spaces we occupy?

I think Zohran being mayor shatters a lot of stuff because it became a global phenomenon. He became the world’s mayor, right? I think we still have a lot to shatter, so I'm not coming from a place of saying it has shattered. I think we have to continue make records. I think we have to put ourselves out there.

I also think we have to show and prove, and just remember: we are guests, right? Black people are culture, and they are the ones that gave us the piece and showed us how we can do this. In a broader sense, everything we do, from what we wear to our influences come from hip-hop and from black culture. Look how long they had to make hits for — whether in film or fashion or music, to even get to the point they’re at right now. Who are we to think that could come in, do this shit for a couple of years and be like, “Yeah, yeah — we in here.”

I think Latinos have been working for so long, and now you're seeing the fruits of their labour. From when it started with Mark Anthony, Shakira, and Fat Joe, to now, fast-forwarding to somebody like Bad Bunny who could be the biggest in the world.

I think it takes all of those archetypes to become that andI think we're in the place of creating our archetypes now.

All of this positivity also comes on the back of a tremendous wave of anti-asian sentiment across North America and Europe. Do you see yourself shouldering some of the responsibility for pushing back against this hate through your music and the stories you tell? Does the weight of that representation ever feel like too much?

It's never been a balance, man. That's just my life. I'm an actual immigrant. I moved here when I was four, and I didn't get my citizenship until I was until 2019, right? So those things that I talk about are as natural as breathing. This is my life. This is what I went through. I am a lower-income kid who grew up in a one-bedroom apartment with six people in it. And I didn't have my papers for a long time, and we couldn't go back home. And the opportunity, you know, the privilege of travel, was not given to us.

My father was a cab driver; my mother was a cashier. Where do those people live? Where do those people, you know, create community? It ain't in the big houses, right? It's going to be in certain neighbourhoods, and all I can do is talk about my experiences, and I think that just represents a lot of people in its own way.

But I never wake up going, “Today. I'm gonna make sure I talk about these guys.” I've been talking about immigration since the start of my career. It just so happens immigration is a fucking topic every four years, you know?

My best friend told me something two years ago, and it's never left my brain since he said it. And he said, “The freedom of surrender and the freedom I feel from surrendering and not letting someone's opinion affect me is unbelievable. If the end goal isn't productive or fruitful, and I’m still thinking about that thing, it's just ego. And I found freedom in surrendering that ego. I don't care what anyone says about how I should balance it. I am a human being. I sometimes like to party.

I could be talking about immigration and ICE and things like that, and I do talk about that, but I also want to be at the party and be the life of the party. And I think I am both of those things. I think it's cool to be conscious, but I also think it's cool to sometimes let go and not think about shit when you don't wanna think about shit.

How do you think your own approach to your craft has evolved as you’ve matured? What are some specific influences that shaped the way you look and create music? Is there an artist or individual — past or present — that you feel a kindred spirit with?

Let's start with, um, my process and how it's been different. Songwriting has been the biggest thing. So, almost every record on this project that you heard started with just the guitar. Matthew Morgan, my manager, told me that if the song doesn't sound good with just you and the guitar, everything else is just makeup. And that kind of really hit me like. I said to myself, “I would really like to improve my songwriting abilities.” And I took three years to do that.

And although it has a lot of hip-hop influences, all the songwriting followed a pop structure. So that took a lot of learning, and that was the most incredible part. It was exciting. I felt like I wasn't the smartest in the room anymore, and I got to learn again. And that was really, really, really, uh, incredible and, and enticing to feel.

There are so many influences, but if I can name some immediately, Nipsey Hussle, Amy Winehouse, Prodigy, Bob Marley, and A.R Rahman are just a few. And in terms of an artist that feels like a kindred spirit of mine, it’s got to be Bob Marley. In no way, shape, or form do I think that I should be compared to him because that man was incredible, but just spiritually, he made so many positive vibrations, and he represented a culture. It was a time when nobody gave a fuck about reggae, and he didn't care. He just kept doing it. And now it's one of the biggest genres on earth. He just stuck to his convictions. I love any artist who sticks to their convictions, and I have a soft spot for people who had to do it the hard way because that was just their upbringing.

And that's how I feel. I've had people offer me to do a bigger record in India. I've had people ask me to do a full Bangali record and things like that and it’s not that I don't, and not that I won't — I will, right? I love my culture, but I am from Queens, and to do that wouldn't be a full representation of who I am, and so if my journey takes a little bit longer in order for me to show off the diversity I come from, so be it.

What does hybridity mean to you personally from the perspective of identity? Many people who grow up between cultures feel a sense of disconnect — like they’re neither here nor there; that they’re not white enough for white people and not brown enough for your own people. How did you reconcile that as you grew up? How does your own hybrid identity inform your specific approach to music?

I think I strayed away from our culture, you know, like any kid. And when you grow up in New York, you have to fight to be who you are. Anyone would run away from that, right? I would lie about my identity just so people wouldn’t beat me up.

And that is an American thing for a lot of people. That is a very immigrant journey. And obviously, assimilation is interesting, and I have a lot of empathy and grace for people who choose to do that. I don't think there's a right answer to it. People who want to assimilate, I don't know their journey. They might need to protect themselves, or they might need to feel better about themselves. I did that for a little bit, but it got to the point where I knew my culture was incredible. I saw that Puerto Ricans love being Puerto Ricans; Jamaicans love being Jamaican; why don't I love being Bangla? Why am I the only one outta everybody that's like, “Yeah, I don't have that many brown friends.” That's not a cool thing to say, but I used to say it.

It was an awakening of sorts. I told myself that I'm gonna own it. And that's what this entire album is about. It’s about accepting that living in that hybridity.

What’s your vision for the future of your music? What would be ‘the dream’ for you as an artist currently? Do you have anything you’d like to say to Homegrown readers before you sign off?

I mean, there are so many answers for that. I want to be an established and identifiable brand not just in the East, but also in the West. I want to be able to sing for people all over the world, and I want them to be connected through melody and feeling more than language. I don't care if you don't understand me as much as you feel me.

And I think that will be the best way to continue to share my culture and my music and the incredible things that come from our South Asians. You know, I just recently did an ‘On The Radar’. I had my gamcha around my head, but I was rapping like I was from the Queens.

And that's the duality that I want to live in. I want to do whatever that was with whatever colours were around my waist, you know, I want to be able to do that ten times over with everything — whether it's film, fashion, music, or festivals.

I want to put our culture in the foreground and show how beautiful we are as a people.