- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

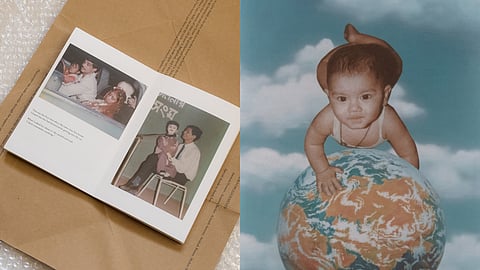

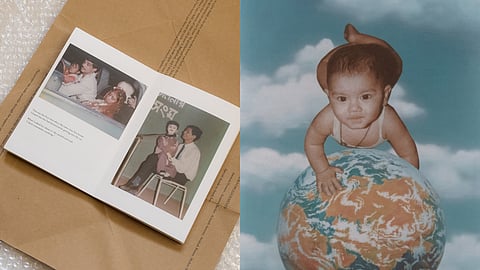

‘Scissors & Glue’, Kolkata-based photographer Rajat Dey’s recounstructed family archive in fragments, probes the unstable terrains of memory, displacement, and intergenerational loss. Drawing from his family’s exile during the 1964 East Pakistan Riots and the demolition of his wooden childhood home in India, Dey constructs a non-linear visual narrative through collage, cuts, and folds on a single sheet of paper.

We live in time — it holds us, moulds us, folds us, and unfolds us. In his doctoral thesis on the nature of consciousness, ‘In Time and Free Will’ (1888), the French philosopher Henri Bergson frames our perception of time, or psychological time, as a form of internalised time, the frequency of which depends entirely on the emotional intensity of a particular moment or memory. Our memories have their own time-logic, completely independent of physical time. Within the inescapable confines of the human mind, time is not an absolute — time is malleable. Some memories quicken its passage; others slow it down. Even though our memories are supposed to be recollections of past events, they are, in themselves, uncertain, inadequate, and difficult to order.

Kolkata-based photographer Rajat Dey’s photo essay, ‘Scissors & Glue’, follows this non-linear logic of memories. “I believe that main historical events create local impacts, which then create individual stories like those of my family. These stories don’t always run parallel to history; they often deflect from it. I call these ‘storyless stories’. They are trivial and have no distinct end. They are shaped by people over time and built out of small packets of emotion. This book is my momentary response to how my family has changed before my eyes,” Rajat says.

‘Scissors & Glue’ is an inquiry into the unstable terrains of memory, history, and identity — a body of work shaped as much by what is absent as by what is present. Its unbound form reflects the precariousness of the memories it carries: the wooden, two-story joint family house built in the late Eighties where Dey grew up; his grandparents’ exodus to India during the 1964 East Pakistan riots triggered by the Hazratbal shrine incident at the other end of the subcontinent; and the absence of any photographic keepsake of either their ancestral home in East Pakistan, or the wooden house which was eventually dismantled in its entirety. “I wanted to explore the stories I heard as a child — stories of a time I never actually witnessed,” Rajat says.

The book is crafted from a single sheet of paper folded into 32 pages, drawing inspiration from the Japanese tatamimono book-making technique. Its design rejects linear sequence, reflecting the non-linear nature of memory — highlighting how recollections can waver, intersperse, reverse, and invent to fill gaps. Dey’s work originates from this anxiety about what must be fully remembered, a common feeling in regions affected by colonial borders, civil wars, displacement, and violence that have systematically disrupted personal and collective histories. Through collage, superimposition, and reassembly, he presents memory as a process of reconstructing these fraught presences and absences. Unfolding the book and folding it back in reverse presents the same story from a different perspective.

These images do not pretend to restore a lost past; instead, they expose the labour of making meaning from fractured, almost-forgotten family histories and memories. In doing so, ‘Scissors & Glue’ highlights the limitations of the photographic form, which has historically been burdened with claims of evidence and truth. Here, photography cannot verify the past because there simply are no photographs of the old house in its entirety — no visual trace of the ancestral home in East Pakistan. What photography can offer instead is a conceptual and emotional scaffolding, a space where imagination supplements the gaps left behind by time and geography.

‘Scissors & Glue’ stands out as an act of meaning-making that challenges ethno-nationalist attempts to overwrite complex pasts with monolithic narratives. By foregrounding the minor, the domestic, the trivial, and the affective, Dey refuses the grand sweep of official historiography. His ‘storyless stories’ resist the idea that only grand events matter by making visible the lived realities of ordinary people navigating oppressive structures.

Follow Rajat Dey here.

If you enjoyed reading this, here’s more from Homegrown:

Mothers & Goddesses: Photobook ‘MATAJI’ Is A Visual Meditation On The Divine Feminine

Aashna Singh And Farheen Fatima’s New Photobook Examines The Hidden Cost Of Housework

10 Photo Books That Will Take You On a Stunning Visual Journey Across India