- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

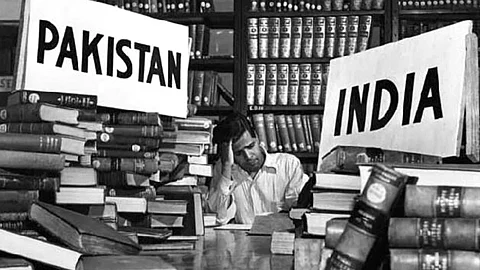

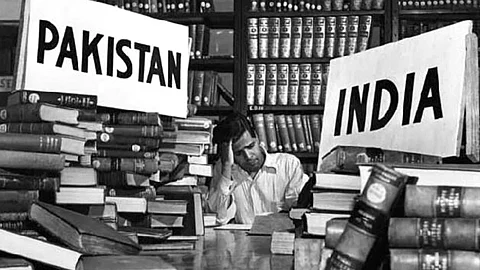

In India, when we speak of the Partition, we often mean the cataclysm of 1947 — the Radcliffe committee’s hurried slicing of British India into India and Pakistan, the largest mass migration in human history, and the blood-soaked history of communal, ethnic, and religious conflicts that followed. But this was not the only partition of India. Earlier partitions — the bifurcation of Bengal in 1905, the separations of Burma and Aden (modern-day Yemen) from British India in 1937 — and the 1971 liberation of Bangladesh formed a series of ruptures that collectively reshaped the political, cultural, and psychological landscape of South Asia. These partitions locked in border conflicts, hardened national identities, widened social faultlines, and prevented the region from evolving into an integrated political or economic bloc.

The First Cut: The Partition of Bengal (1905)

This cycle of partitions began in 1905, when Lord Curzon — the Viceroy of India (1899-1905) — split Hindu-majority western Bengal (present-day West Bengal) from Muslim-majority eastern Bengal (present-day Bangladesh), creating sectarian tensions that would fester for decades. Officially, the bifurcation of Bengal was an administrative move. In reality, this was another classic example of the British divide-and-rule doctrine at play.

The backlash was immediate. Literature and the arts became media of popular resistance: Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay’s ‘Vande Mataram’ became a revolutionary anthem; Abanindranath Tagore painted his iconic Bharat Mata, imagining India as a benevolent mother; and the Swadeshi movement led to the boycotting of British-made goods and promoting indigenous industry.

At the same time, many Muslim leaders saw the partition of Bengal as an opportunity to escape the Hindu hegemony over the Indian independence movement. Though the division was reversed by Curzon’s successor Lord Hardinge during the Delhi Durbar in 1911, it had already set dangerous precedents. The All-India Muslim League was born in its wake, and the idea of Hindus and Muslims as opposing identities was hardened. Bengal’s sense of itself would never fully be the same again.

The Unravelling of Empire: The 1937 Exits of Burma and Aden

In 1937, another significant but lesser known partition took place: Burma (present-day Myanmar), administered as part of British India since the Third Anglo-Burmese War in 1885, was made a separate Crown Colony. In Rangoon (Yangon), Indians — who made up 7% of the population but paid over half the city’s taxes — became foreigners overnight. The borders split ethnic communities and commercial networks, and thousands of Indian migrants found themselves stranded or expelled. These separations hinted at what was coming: a looming imperial unravelling that would leave entire peoples without a nation.

Surprisingly, even Mahatma Gandhi, often regarded as the great unifier of India, supported Burma’s separation. “I have no doubt in my mind that Burma cannot form part of India under swaraj [self-rule],” he said — echoing the broader Hindu nationalist belief that the idea of India, as Bharat, the sacred land evoked in the Mahabharata, did not include regions like Burma or Arabia within its boundaries. In some ways, the exit of Burma from British India solidified the nationalist idea of a modern India, and sowed the seeds of the two-nation theory by equating the idea of India with the Hindu civilisational image of 'Bharat'.

The same happened with Aden, the Yemeni port that had long been part of the Bombay Presidency. The exit of Aden created a degree of separation between the Indian nationalist movement and the Arab nationalist movement, and by extension, Indian Muslims and the Muslim world.

Independence and Upheaval: Creation of Pakistan (1947)

The partition of British India in 1947 stands as one of the most catastrophic instances of territorial division in South Asian history. As the British exited, India was divided into Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan. Between 14 and 20 million people were displaced in the largest mass migration and population exchange in history. Up to two million died or disappeared permanently. Trains filled with corpses crossed the new borders almost daily; cities burned; Punjab and Bengal — split again — saw neighbours become enemies overnight.

Yet even as it tore the subcontinent apart, the Partition forged new political realities and collective consciousness. Pakistan framed itself as a homeland for Muslims and India chose secularism as a guiding principle. The rupture redefined identities, communities, and national mythologies. It also seeded permanent hostilities. Kashmir — whose contested accession resulted in four wars between India and Pakistan (1947-48, 1965, 1971, and 1999) — became a flashpoint and remains one of the most militarised regions in the world.

1971: The Final Act of the 1947 Partition and the Birth of Bangladesh

The final act of the 1947 partition unfolded in 1971, when Pakistan was divided into two. The Bengali-speaking East Pakistan had long endured under West Pakistani rule, facing political marginalization and linguistic repression. When the Awami League won national elections in 1970 and was denied power, Pakistan erupted into a full-scale civil war between the East and the West. The Pakistani army launched a brutal crackdown on Bengali rebels. India intervened. Nine months later, East Pakistan became Bangladesh.

For South Asia, it was a turning point. The two-nation theory that justified 1947 was shattered. Religion alone couldn’t hold a nation together. Language, culture, and regional identity mattered too. The birth of Bangladesh reshaped the political and emotional geography of the region.

2019: The Bifurcation of Jammu & Kashmir

On August 5, 2019, the Indian government revoked Article 370, stripping Jammu & Kashmir of its constitutional autonomy and splitting the state into two Union Territories. The move was sudden, enforced with lockdowns and mass detentions. For many Kashmiris, it felt like a second Partition. India claimed the reorganisation would bring development. But to many, it appeared as demographic engineering. The only Muslim-majority state in India was being reimagined from Delhi, without local consent. The echoes of 1947 were unmistakable: contested borders, fractured identities, and a people caught in the crosshairs of nationalist imaginations. In many ways, it was the culmination of the Kashmir dispute, which stemmed from the self-fulfilling logic of the two-nation theory and the 1947 partition.

Fragments and Futures

From the first cut of Bengal in 1905 to the carving of Jammu & Kashmir in 2019, the story of South Asia is written in these ruptures. Each partition tore through maps and communities, redrawing borders and reimagining identities, often along lines of religion or colonial convenience.

These partitions created new nations, national identities, and monomyths, but they also introduced new voids shaped like the other. Entire communities vanished from official memory: Sindhi Hindus; Kashmiri Pandits; Punjabi Muslims. Yet, they left cultural footprints in the form of diasporas, preserved languages, oral traditions, and family histories.

Despite these many divides, the region’s culture remains deeply entangled. Today’s India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh still echo with the sounds of the same songs, stories, and histories. This is the paradox of partition: a history of fragmentation that somehow produced a shared canon across countries.

South Asia today is a mosaic of these fragments. Shared cuisines, music, cinema, and poetry transcend the geopolitical borders created through colonial violence. Immigrants and refugees carry memories across generations. Despite political hostilities, the cultural imagination remains porous and fluid. To understand modern South Asia, then, we must reckon with these partitions: not only as historical events, but as ongoing processes. And in the spaces between these ruptures, we must find both solace and resilience — and the shared hope of some semblance of reconciliation.

To learn more about how the many partitions of the Indian subcontinent shaped modern South Asia, read Sam Dalrymples 'Shattered Lands : Five Partitions and the Making of Modern Asia'.