- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

In recent weeks, many Bengali migrant workers have been falsely identified as "Bangladeshi" in North Indian states for speaking Bengali, as part of a police crackdown against "illegal infiltrators". In some cases, these workers — often from Muslim, Dalit, Bahujan, and other historically oppressed communities in rural Bengal — have been detained and deported to Bangladesh despite possessing documents that prove their Indian citizenship, only for the Government of West Bengal to intervene and bring them back.

This new phase of exclusionary language politics has sparked fresh linguistic anxieties among Bengali migrant workers, leading many to return to their hometowns and villages en masse. As a result, North Indian cities like Gurugram have experienced significant sanitation problems, since many of these migrant workers are typically employed in blue-collar roles such as maids, cleaners, janitors, and garbage collectors across the country.

As online debate rages on about whether or not the detained migrant workers are Indian Bengalis or "Bangladeshis" — a right-wing dog whistle for Bengali Muslims — many xenophobic commentators have made viral posts about how to identify Indian Bengalis and Bangladeshi Bengalis using the supposed differences between Arabic, Persian, and Urdu loanword heavy "Bangladeshi" Bengali and Sanskrit-adjacent Indian Bengali. But this line of thinking is as absurd as it is indicative of a lack of understanding of the Bengali language, the Bengal region, and Bengal's sociopolitical and linguistic history. India's first Urdu newspaper, published by a Bengali Hindu, edited by a Punjabi polyglot, and printed by a British East India Company employee, is a testament to how language has always been a bridge between Bengal's fluid, multi-ethnic, multi-linguistic, and multi-cultural reality.

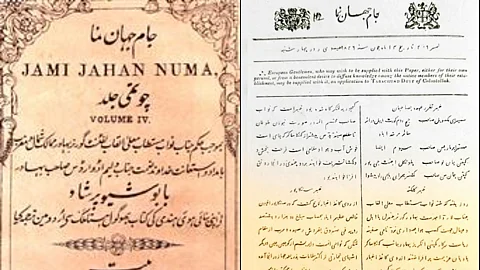

Launched on March 27, 1822, in colonial Calcutta, the newspaper was named 'Jam-i-Jahan-Numa', meaning 'The World-Revealing Cup'. Its name was inspired by the mythical wine goblet of the legendary Persian king Jamshid, believed to reflect all the events of the world. The newspaper lived up to that promise by publishing a wide range of news — local and international, scientific and social, moral and political — while remaining fiercely independent. Even as it occasionally received British patronage, colonial authorities feared its potential as a driver of public opinion and introduced India's first press regulations in 1823, partly in response to its growing influence.

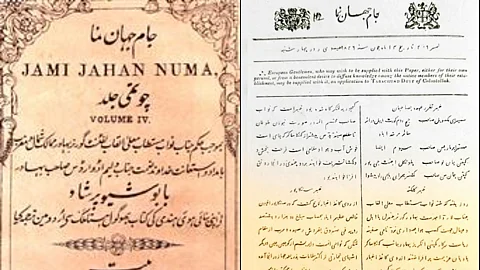

The Jam-i-Jahan-Numa was a professionally formatted weekly newspaper comprising three sheets, or six pages, in a compact, quarter size. Published every Wednesday, each issue featured pages divided into two columns, with approximately 22 lines per column. Measuring 20×30/8 centimeters, the newspaper was priced at 2 Rupees per month. The publication day — Chahar Shambah, the Urdu word for Wednesday — was prominently printed below the masthead along with the date on every issue.

And yet, despite being the first Urdu-language newspaper in India, the Jam-i-Jahan-Numa was not a Muslim enterprise. Its publisher was a Bengali Hindu named Harihar Dutta, the son of reformist journalist Tarachand Dutta, the co-founder of Sambad Kaumudi — a Bengali weekly newspaper published from Calcutta in the 19th century that actively campaigned for the abolition of the Sati practice. Its editor, Munshi Sadasukh Lal, was a Punjabi Hindu from Agra who was fluent in Urdu, Persian, Arabic, Sanskrit, and English; and its printer, a British man named William Hopkins, was a former employee of the East India Company. It was a product of this confluence of cultures — from the Gaur Sultanate to British colonialism — that shaped the modern Bengali language and identity.

Today's narrow identity politics on the basis of religion, ethnicity, and language seem to punish precisely this diverse heritage. Over the past few years, there have been disturbing instances where Bengali-speaking migrant workers were persecuted in Hindi-speaking states like Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, and Gujarat on suspicion of being "illegal Bangladeshi immigrants". That they spoke Bengali, or rather non-standard dialects of Bengali prevalent in rural Bengal, was often enough to mark them as foreign, despite possessing Indian identity documents.

Such acts of linguistic othering are not only cruel — they're historically illiterate. The Bengali language, like Urdu, has never belonged exclusively to one ethnicity or religion. It has absorbed, adapted, and evolved across centuries, shaped by Sanskrit, Persian, Arabic, Portuguese, and English influences. Calcutta itself, where Jam-i-Jahan-Numa was first published, was once a city where Bengali, Urdu, and Persian coexisted in everyday life. To reduce Bengal's complex, multifaceted linguistic identity to national borders less than a century old, then, is tantamount to erasing millennia of many-layered history.

Ironically, even Jam-i-Jahan-Numa itself had to adapt to the multilingual realities of its time. Originally published in Urdu, it switched to Persian — one of the official languages of Bengal at the time — within weeks due to limited readership, then brought back a 4-page Urdu supplement a year later. As India marks the bicentenary of Urdu journalism, looking back at Jam-i-Jahan-Numa reminds us that language, until recently, was not a battleground but a bridge in India. Its legacy lies in challenging the false binaries we impose on ourselves today — between Bengali and Bangladeshi; between Urdu and Hindi; between Indian and the 'Other'. Borders in South Asia are man-made legacies of colonialism. Our languages — like Bengali, Urdu, Sindhri, and Gurmukhi — are fluid, living traditions torn between shattered homelands. And yet, they are the ever-evolving, ever-migrating bridges that remind us that we are one people.

If you enjoyed reading this, here's more from Homegrown:

One Man Is Saving Hundreds Of India’s Lost Languages

5 Homegrown Writers Who Are Reclaiming The English Language From Its Colonial Legacy

5 Language Movements That Dented Socio-Political Operations In India