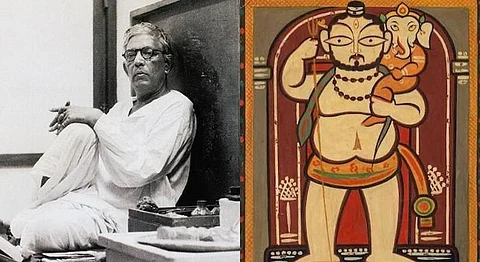

Jamini Roy: India’s First Modernist Painter Who Chose Kalighat Over Western Art

Indian folk art and its various forms are supremely distinct from one another. Each area and community’s cultural influences seep into these art forms to give us what we have seen over time. Given India’s vast and diverse nature of art, folk art is not limited to a certain audience, and Jamini Roy, one of India’s first modernist artists understood that perfectly.

Roy was born in 1887 in the Beliatore village of West Bengal into a family of landowners. At the age of 16, he left home to move to modern-day Kolkata to enroll himself in the Government College of Art, where under Abanindranath Tagore, he received a Diploma in Fine Arts, and had begun to find his footing in Western classical ways of painting. He did as his education demanded and pursued classic modern art. However, around the year 1925, he came to the morose realisation that this style of art, as beautiful as it is, was not what his heart desired. For long, it is possible that he may have not been aware of what it is that he was after. Then, one day that year, as he was passing by a Kalighat temple in Kolkata adorned with Kalighat paintings, it struck him. Almost like an epiphany, he realised that this is the art form his heart has been chasing.

What is commendable is that it was not simply the appeal of Kalighat that touched his heart, it was all that Roy could do with it. Kalighat was known for its bold use of colours and depictions inspired by Indian gods and mythological characters, and was a prominent Indian folk art that evolved into a means of showcasing the everyday Indian’s life. Roy’s thought process shifted. He felt that Kalighat made for the perfect vehicle to not only feel connected to his people through art but also take back the power that Western styles then held. In an attempt to explore and celebrate his Indian-ness in its true sense, he decided to give up Western classical art, and took up this Indian folk art.

Around the 1940s is when his work in this field began gaining traction. IN 1938, his work was displayed on a British-ruled street in Kolkata. Slowly but surely, Indians in Kolkata began purchasing and appreciating his work. Quite surprisingly, even the Britishers took notice of his work. Later on, his work would be presented in London and New York –– turning folk art into a global marvel.

Shedding the entire purpose of his education and denying British academic forms of art could not have been easy for Roy, especially pre-Independence, but it was the time that it called for most. When Indian push-back against British rule was at its highest, the larger movements were fueled and encouraged by such acts. When Indians saw a renowned artist let go of European influences to flourish in the glory of Indian art, it brought about a sense of unity and power.

Contrary to old-age beliefs, art is supremely political –– it is political when you wish it to be. Roy’s 180-degree turn from Western to Bengali art stood for far more than appreciation of the latter; it stood for the refusal of oppression and the abolition of inferiority.

In 1954, Roy was awarded the Padma Bhushan. He passed away in April 1972, but something tells us it was not India’s third-highest civil award he would have called his life’s achievement –– it would have been the impact he left on India with his politically-charged art.

Roy’s work is being archived and presented online by the Instagram page ‘Jamini Roy Art’. It can be found here.

If you enjoyed reading this, we suggest you also read: