- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

More than the time or my age, I remember the moments following my first reading of the poem Howl. There’s no way you can read this poem just once, more so because at your first initiation it seems like nothing but a messy expanse of blatherings that completely go over your head.

It was unlike anything I had ever read before, especially in school and considering the controversial history of the poem and its prolific writer, it’s no real surprise. It’s definitely an experience on its own and is really what the name suggests, something you pick up on more clearly the more times you read each line.

It truly was a howl – sad, yet angry, a declaration by the poet Allen Ginsberg, a loud voice shouting at the socio-cultural system in America of the 1950’s that Ginsberg writes, led him to bear witness to “the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness.” Everything about the poem is explicit, from its language, themes of drugs and sex (both heterosexual and homosexual) as well as the social and literary effect it had on the bland landscape of the United States (and in time, the world).

This poem, written around 1954-1955 and published in 1956, was so explosive that it was publicly condemned at a legal trial and Ginsberg charged with obscenity. Howl has gone down in history as one of the most powerful, great works of American literature, and become one of the hallmarks of the Beat Generation – a movement that triggered one of the greatest displays of counter-culture, with Ginsberg’s face among those in the forefront.

The magnetic pull that literary figures of the past have over young writers of today is hard to put into words. Nothing seems to attract a writer more than the Beat generation. Young, scruffy anti-establishment writers living life on their own terms and rejecting dominant societal rules has a kind of attraction that makes you fantasize about travelling across cities with Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, with the sun shining on your face – there’s definitely someone playing the harmonica – living the ideal hippie writer’s life you’ve imagined through a romanticised notion of the Beats.

So with all of this in mind, imagine my surprise when I learnt that during 1962-63 one of the greatest literary figures of modern times (well, at least in my mind) had lived and travelled across India, between Calcutta and Benares, as they were then known. This was my Midnight in Paris moment; wishing I could magically ride off into the night and sit in an opium den located in the lanes of Old Delhi, discussing life, love and all its matter with Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky, his lover with whom he has travelled to India.

In those days, India was pretty much viewed as the mystic orient sitting on the edge of the world for the most part of the American imagination; this was before the Beatles’ infamous trip to Rishikesh. Ginsberg and Orlovsky immersed themselves into Indian life and culture in ways that we probably don’t even consider today.

What Ginsberg looked for in India, a country so spiritual and deeply religious (more in terms of pure faith that drifted through all aspects of life than a tainted institution), was an experience with God. While my own mind jumped to the conclusion that he was just another foreigner venturing to the country to ‘find themselves’ in an Eat Pray Love manner (ick), his experience and intentions weren’t really the same.

He didn’t search for a spiritual leader or an all-knowing guru to lead him onto the right path, but his curiosity lay in the ordinary – the spiritual in everyday life for everyday people, right from the elites of Bombay to the homeless on the streets of Benares. He wanted to absorb everything he could in terms of culture and spirituality. Ostracised by American society following his trial, Ginsberg wanted to find a connection with Indians that faced the same, living on the fringes of society, be it social or economic outcasts.

Thankfully for me, and million other Ginsberg enthusiasts curious about his tryst with India, he documented his entire journey in graphic detail in the ‘Indian Journals’, right from the people he met, including Bengali Hungry poets, saints and sadhus, lepers in Benares, writers, high society members to the food he ate, subsequent diarrhea and every site and scent he encountered on his trip around Delhi, Mumbai and Calcutta.

Ginsberg was more than just a tourist. He put to words his overwhelming emotions of experiencing the Manikarnika ghat and burning pyres, expressing in his typical fashion the sense of peace that accompanied the mourning and death. These were feelings, experiences and emotions that tapped into a part of him he couldn’t find in the industrialised and military-driven institution that was America in the 50s-60s. You find in Indian Journals bits and pieces, lucid dreams, poems and drug-induced scribbles that captures and Indian experience before the ‘hippies’ discovered the East.

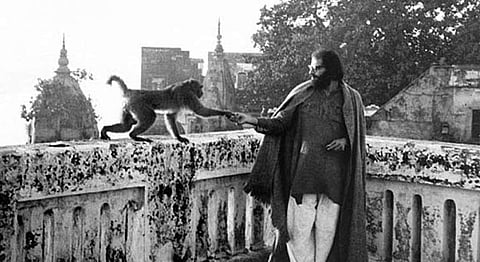

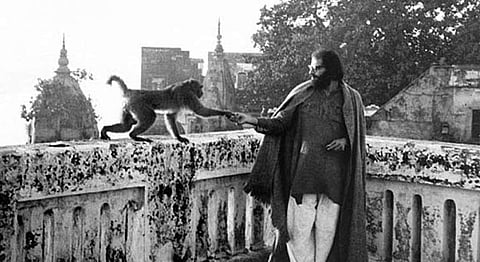

What probably caught his fancy more than anything was the ease and openness with which people practised their religion, especially in Benares. The sight of a sadhu with dreadlocks and nothing on but a loincloth strolling through the streets, zigzagging his way through a bustling crowd where no one even batted an eyelid was incredible and unusual in the best way possible – something that would be completely bizarre, even rebellious, in the US.

There was undeniably a prevailing sense of romanticism when it came to the way he viewed India and its people. He saw a certain side of it in isolation during his time in Benares, and it catered perfectly to his poetic imagination of the ‘exotic’ and ‘mystic’ aspect of Hinduism and religious practice in India. Other than Benares his visited a number of Buddhist sites as well and met famous religious leaders and gurus including the Dalai Lama.

During Ginsberg and Orlovsky’s time in Calcutta, they met and even briefly lived with local poets such as Malay Roychoudhary, Sunil Gangopadhyay and Shakti Chattopadhyay. While popular notions hold that it was Ginsberg’s visit that inspired India’s own Beat generation to kick off, Tridib and Alo Mitra posit that it was, in fact, the Hungryalists that influenced Ginsberg [read more about it here].

However much he tried to not be an outsider it was hard to drop the white man’s gaze after a point if we’re honest, something that does make itself evident in his Journal. As Ranjit Hoskote, poet and cultural commentator explained to Jeet Thayil for the BBC, “On the one hand it’s a perfectly legitimate form of an encounter but in this particular transcultural context, it’s difficult to disentangle it from Orientalism.” He goes on to express that it’s because we’ve already suffered at the hands of curious ‘visitors’ from the West before that are searching for the ‘real and authentic’ India.

Ginsberg even did a reading at the English department of the Banaras Hindu University, and as was the result in America, here too his work was found offensive and a case was filed against him, according to BBC. Ginsberg and Orlovsky’s presence seemed suspicious and drew a quite a lot of negative attention – some even thought they were CIA agents undercover.

While Indian cities and its people accepted him, the administration yet again found an enemy in Ginsberg. But it wasn’t for politics or the fixing of social evils that he came to India for, but a personal journey for connection, insight and moreover, love – of people, literature and culture.

While he may have not actively inserted himself into Indian politics, Arthur J Pais writes that he fell in love with Gandhians such as Shankarrao Deo and cultural activist and writer Pupul Jayakar. Pais writes that Ginsberg grew to admire Deo’s conviction regardless of the lack of support and even ridicule he faced regarding the unsuccessful march from New Delhi to Peking (Beijing) to bring about peace between India and China. Other than Buddhism, this is among the few important things that Ginsberg took back with him to America – non-violent dissidence.

However much he tried to stay out of politics, he came to India and returned to the US at turbulent times for both countries. He took this new found method of protest to the American streets during the demonstrations against the Vietnam War.

He used his notoriety for good, so to speak, especially in the 1968 Grant Park riot in Chicago. Ginsberg chanted Om for hours on end, until he lost his voice while sitting on the road drawing the attention of not just the media but the people around him. The non-violent protests he witnessed in India became a major part of the political figure he would soon become back in the US and an important aspect of his protests during the Vietnam War, as well as the countless others that followed him.

I guess we’ll never fully know whether Ginsberg found what he was looking for when he came to India. Whether it was visiting Hindu and Buddhist pilgrimage sites, encountering the Bauls and sitting at a coffee house with Hungryalist writers. Or his stay in a Jain Dharamshala in Old Delhi because that was all he could afford; the impact this experience had on him, how it moulded his thinking, ideology and personality is clear in his own words and actions.

Maybe he did really ‘find himself’ in India through his poetic imagination, however much I dislike that concept. Ginsberg might have been on his own search for connections through his life, maybe he didn’t realise that he himself would become an iconic literary figure who exudes anti-establishment sentiments that many young poets and writers will continue to find a bond with for years to come.

If you liked this article we suggest you read: