- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

Freedom of the press is vital to any functioning democracy, but we are in a global moment where it is continually undermined. India is no exception, as many communities find their struggles and stories pushed to the sidelines of mainstream media. But under the country’s carefully-curated status quo, there exists a thriving community of artists and activists shedding light on the most forgotten populations, giving them visibility and a voice louder than ever before. Documentary photographers, in particular, have always had the uniquely important task of preserving emotional truths, passing down veracious histories, and capturing the social and political realities of our contemporary society, however big or small.

Here are five under-the-radar documentary photographers who have boldly and beautifully taken on the dominant cultural fabric of India, challenging age-old truths equipped with nothing but a camera.

Born in Punjab, raised in Delhi and with a degree in photography from NYU-Tisch, Karanjit’s work is a beautiful ode to two communities who have known a great deal of historical trauma: the Sikhs and the Tibetans. Working with a vivid, soft light palette, he traces the history of the Sikh diaspora in New York – featuring the symbolic weight of the turban in a time of American xenophobia – and contrasts it with life in Punjab, where the turban is neither glorified nor targeted. He shows through his sometimes-startling imagery how cultural artefacts like the turban are exported into exoticised and reductionist narratives by a Western gaze. Having lived in New York himself, Singh is no stranger to the racism felt by immigrants. His work reflects that reality and calls out global audiences for their inaction.

Similarly, his most recent project, ‘Exile is a memory of a beloved’, is a melancholic one that brings to life the protracted sorrow of thousands of Tibetans who fled China in the late 1950s. “A little boy sits in his orphanage bedroom, looking out the window where he sees a snow-laden mountain and mistakes it for a Tibetan landscape because it reminds him of a half-forgotten journey he took as a baby tucked in his aunt’s rucksack,” he writes by way of description. His photographs document the everyday lives of refugees in India, including trans and queer persons within these diasporas, dismantling societal misconceptions and giving visibility to people who have been on the sidelines for centuries.

Having grown up in a small town in Uttar Pradesh, Deepti Asthana is a self-taught documentary photographer now based out of Mumbai. Her work focuses on gender parity particularly in rural villages and small towns of India. Using what she describes as a “natural, non-artistic lens,” she documents the struggles and hardships faced by many rural women. She elevates stories that have been in the shadows and don’t ever make it to mainstream media.

Her most recent project, titled ‘Divided by Partition: the Baltis of Kargil’ is a beautiful series about the women in Baltistan, a region of Kashmir that lies between Ladakh, Afghanistan, Punjab, Tibet and parts of China. In the 1970s, the changing geopolitics of the region caused the Balti population to disperse into many villages, which now belong to different governments. As a result, families have been separated and women, specifically, have been affected as many such border villages are subject to privacy and dignity violations in the name of securing borders.

Her photo-series evokes the resilience and courage of these Balti women as the long-term impact of the Partition has melted into a stagnant political status quo. She photographs them struggling to keep their traditions, language, food, and culture alive as the diaspora continues to fade away. Her work serves as a reminder to her urban audiences of the changing rural landscapes that ought to be integrated into everyday understandings of Indian politics.

III. Parth Gupta @parthgupta__

Parth Gupta is a Delhi-based documentary photographer whose work is a deeply personal exploration of emotions and emotional spaces. His first connection to the visual was through his old family albums, and the experience of engaging those photos is the spirit that guides all his work, including a breathtaking portrait series on the famous 92-year-old calligrapher Manzooruddin and another one on the longing for open space in a rapidly urbanising India. He photographs stories and trends that go unnoticed in the vast cultural landscape of India.

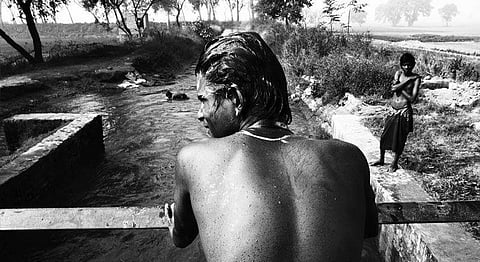

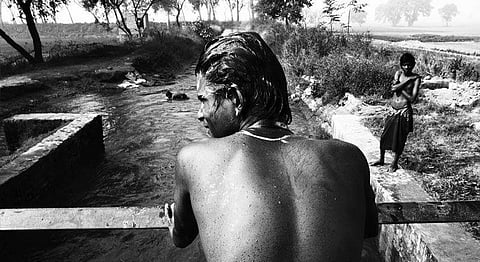

A recent project of his titled ‘So Much Water, So Close to Home’ is one of the most poignant and riveting works to emerge in contemporary India. Working in black and white, Gupta photographs the people of Khanauri, a small town in Punjab that has an unusual and disturbing history. The town rests next to a sluice floodgate that gushes water out from the Bhakra Main Line Canal, an inter-state channel that carries water from the Sutlej to hundreds of villages. At Khanauri, where it diverges towards Rajasthan, is the spot known as the floating ground for corpses. “It’s a gruesome spot. The stench of rotting flesh hangs in the air and in the garbage-caked water, and there are almost always a few dead bodies floating on its surface which were not identifiable,” writes Gupta.

These bodies belonged to the hundreds of thousands of farmers who committed suicide in the last 5 years. Farmer suicides have been the biggest failure of neo-liberalising India’s agrarian economy, especially in Punjab. What Gupta manages to do is merge a growing economic crisis with the horrific normalisation of tragedy within the dominant status quo of rural life. His photographs show the people of Khanauri going about their day as though the stench and presence of death all around them wasn’t there. He has captured with ferocity and bitter irony the heart of our postcolonial, bureaucratic nation.

Based between New York and New Delhi, Akshay Bhoan is a photographer focused on the visual study of trauma, migration and memory. His work relies on artistic interpretations of factual events, which can be seen in the diversity of his projects. From a feature on the “last seen” locations of missing minors in New York, to digging up discarded family photographs in Mumbai, Bhoan has captured an emotional reality that few are able to fathom. One of his projects from 2015, titled ‘Grey Notebooks,’ is a beautiful tribute to Vrindavan – the hometown of Hindu Goddess Radha – and the thousands of exiled and widowed women who have made it their sanctuary of peace and liberation. The project seeks to understand their experiences of love, loss, devotion and sexuality. “It dives deep into issues of identity, role, violence and iconography, questioning if such a mythical sanctuary really exists or is fabricated as part of larger cultural and class identity [customs] in India,” he writes.

Another project, still in progress, titled ‘Mard’ is an especially relevant project that calls out the regressive patriarchy of India and questions male identity at its very core. Through a series of vintage-style portraits of half-naked men, Bhoan sheds light on “generations of men who exist without a self-created understanding of what it means to be a man, questioning their place in a society built on illusions of power.”

Arunima Singh is a photographer, entrepreneur and interaction designer based in Delhi. She co-founded Lucida, a photography collective that promotes a “design-oriented approach” to photography. Her work is informed by a number of theoretical and practical frameworks of social change, but her experimentation with the visual medium is purely as a form of expression. One of her past projects, ‘Under Construction’, is as pertinent today as it was then. It documents the living spaces of workers in congested construction sites. Using natural light and a simple beige palette, she captures the fragility and transience of a little-known reality of workers.

“The motivation behind the body of work is to explore the complexity and vulnerability of the life of a construction worker through these spaces. Details of the delightful and intimate living spaces narrate the character of those living spaces and its occupants,” she writes. Another project, undertaken by Lucida, is an archival-style one about the mobility and safety of women in India. Featuring nighttime, street-lit shots of women in the city’s slums, the work is aimed at shedding light – literally – on the unique issues women face in small communities.

View the full projects on her website here.

Feature image: ‘So Much Water, So Close to Home’ by Parth Gupta.

If you liked this article we suggest you read: