- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

The appearance of certain buildings can be considered ‘distinct’ in a sense outside of ‘peculiar-looking’, too. A library one encountered every day on the way back home from school is as distinct to them as is a whacky blue 33-floored tower to anyone else. What we see and hence, what we choose to remember from the appearance of structures is deeply personal. Some of the things used to build these, however, carry decades worth of stories, and today we focus on that of the ‘Mangalore tiles’.

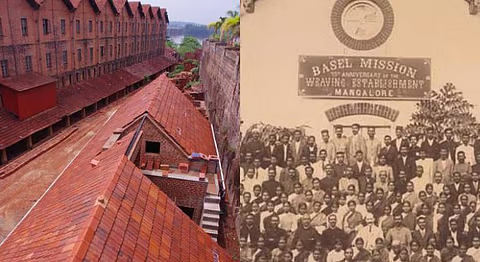

A signature shade somewhere between orange, red, and brown, Mangalore tiles are not difficult to spot. They are usually seen atop homes as part of the roof. If you’re imagining an Indian bungalow, particularly a South Indian one, the red roof is almost definitely made of Mangalore tiles. These days, these tiles are also used to add aesthetic value, texture, and a bit of Indian-rooted identity to modern homes. The inclusion of these outside their intended purpose, in fact, is a wonderful sight.

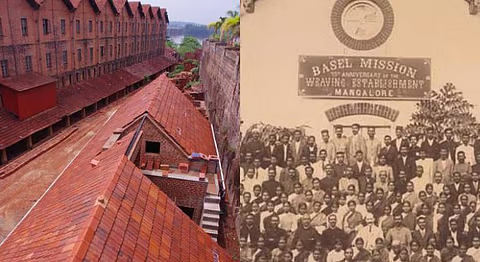

Mangalore tiles go way back in time as part of our infrastructural integrity. In 1865, Basel Mission, a Swiss-German Christian missionary society was set up in Mangalore. It had been active in South India a couple of years prior. They formed the base of the tile industry, apparently to create employment as part of a larger concept of allowing people to achieve spiritual fulfilment. Then came George Plebst, a German engineer, who earned the appreciation for taking charge of this industry and taking it no newer heights. He would take samples of the South Indian clay and test it against the technologies being developed in infrastructure back in Europe when he had to travel back to the Western continent due to poor health. The red laterite clay tiles were thought to be laid out in a French-style, interlocked pattern — which gave the Mangalore tiles their signature look.

This new style and product altogether flourished across the Malabar Coast. The tiles would be shipped to and from the coast to several locations, and eventually, the British took control of the Basel Missionary, before returning it to Indian authorities in 1977.

The now not-so-frequently-used Mangalore tiles played positive roles in the spheres of durability and sustainability. If prepared well, they held the potential to last for decades, and their shape and material allowed for the cool circulation of air. The tiles were used in a widespread manner in the past, even beyond homes. It is believed that with reduced budget caps for infrastructure in government schemes for the poor, these tiles do not make the cut, and are beaten here by cement and concrete. Made from locally found resources, the tiles, while somewhat in line with environmental purposes also hold a contradictory story as the (over) extraction of these resources leads to an unstable and unreliable environment in the region.

Of the seven factories set up by Basel Missionary between 1865 and 1905, only three remain. It is often unnoticed just how inanimate objects and materials, such as these Mangalore tiles and the clay they come from, dictate the visual identity and culture of a place. Unrestricted to the South of India, these tiles feature across the country, and even if people are not aware of the name, the sight strikes a chord of familiarity and the power to do just that is immense.

Creating the face of a home, a sense of community, and a feeling of belonging is brought about by these Mangalore tiles. A bit of clay, some mud, and a few refined processes, all in the past, managed to give India a structural sight we can distinctly call our own.

If you enjoyed reading this, we suggest you also read: