- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

P. C. Sorcar strode onto the BBC stage, adorned in silks, a peacock in a sea of gray suits. On that April evening in 1956, the magician from Bengal was about to challenge Britain’s sensibilities, not just with sleight of hand, but with the very idea of what Indian magic could be. He was a puzzle that refused to be neatly boxed, wrapped in mystery and a touch of scandal.

The magician’s assistant lay on the table. Sorcar raised the roaring buzzsaw above her as millions watched from their living rooms. The show was more than an act. It was an unraveling of preconceived notions. He cut through an ancient narrative — one that portrayed India as a land of mystics who charm snakes.

As the assistant lay still, the screen faded to black. Panic rippled through viewers, and the BBC switchboard lit up. What was seen as a simple magic act transformed into a mass psychological event, one that perhaps only Sorcar could have orchestrated? By the next morning, the newspapers blared, “Girl Sawn in Half — Shock on TV!” and Sorcar became a household name. The show was an illusion, yes, but its impact was all too real.

Born Protul Chandra Sarkar in a small village in present-day Bangladesh, Sorcar’s path was hardly one of ease. He began as a young boy with chalk and paper, practicing basic tricks that soon became more than just games. By the time he was a teenager, magic was a weapon against obscurity.

But Sorcar wasn’t content with tricks in back-alley theaters. He had ambition — an unsettling, gnawing hunger to perform on global stages that had largely shut their doors to magicians from the subcontinent. Western audiences, accustomed to seeing India as the land of ascetics, often dismissed its performers as crude. Yet, here came a man in flamboyant attire, boldly declaring himself “The World’s Greatest Magician”.

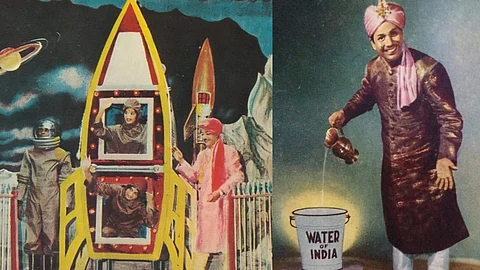

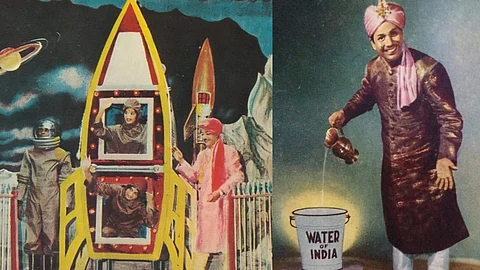

His shows were drenched in colour, ritual, and symbols that harked back to an older India. The stages were transformed into fantastical versions of the Taj Mahal, complete with painted elephants and assistants dressed like figures from Mughal courts. Before the act began, he would draw mandalas and light lamps as if to invite the gods themselves. But there was also something playfully deceptive about it. While Western magicians were refining acts like levitation, Sorcar’s tricks seemed rooted in stories as old as time — of eternal water pots, floating goddesses, and hypnotic drums.

Yet, not everything Sorcar touched turned into applause. The 1950 convention in Chicago marked his entry into the American circuit, but it also brought friction. He came to conquer. When he accused two fellow magicians of cheating, the room split into two camps: one of loyal supporters and the other of enraged detractors. The uproar was as theatrical as Sorcar’s magic itself.

In the 1960s, Sorcar’s reputation was a double-edged sword. Some saw him as a cultural ambassador, bringing India’s mystical traditions to foreign shores. Others considered him an audacious performer pushing boundaries for the sake of spectacle. His acts, laced with risk, were challenges. To enter the British living room and disrupt the mundane was, in its own way, a feat of magic.

The real twist, however, lay in Sorcar’s persistence. The man’s life was less a series of tricks than a long, calculated gamble. He was known to buy space in newspapers to publish glowing reviews of his own shows — an attempt to craft his legacy as he lived it. Sorcar’s defiance extended beyond his tricks and he refused to play by the West’s rules.

The magician’s final act came in 1971, during a tour of Japan. Against medical advice, Sorcar performed one last Indrajal show in Hokkaido. As the audience cheered, the man who had defied gravity, skeptics, and empires collapsed backstage. His son, P. C. Sorcar Junior, would don the same flowing robe, but the original had already imprinted a part of himself into the Western imagination.

In many ways, Sorcar’s story is not merely one of a magician but of a nation reinventing itself. To the world, India was still reeling from the vestiges of colonialism, trying to find its identity. Sorcar offered a glimpse of an India that was both ancient and modern, both rooted and unfathomable. His saw may have been an illusion, but the cuts it made were real.

Sorcar’s magic was less about deception and more about cultural provocation. He forced audiences to confront their own stereotypes, their own ideas of the ‘mystical East’. In the process of doing so, he transcended the limits of the stage. As he once said, “Eastern magic is less about tricks of the hand, more about the power of the mind.”