- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

My first encounter with Shakespeare was in 9th grade, when The Merchant of Venice was part of our curriculum. By then, our seniors had already put the fear of the Bard into us, warning us about how winding, irritating, and incomprehensible it would be. Their advice was simple: stick to the Cliff Notes and you’ll pass.

At first, I agreed with them, it did feel long-winded. Antonio was perpetually melancholic, Bassanio was, well, an idiot, and Portia was clearly the sharpest of them all yet rarely given her due, because, of course, she was a woman.

But then came Shylock. The supposed villain. The antithesis of all those good “Christian” values. And he was marvelous. Suddenly, the play had a pulse. He was the most complex, fully realised character on the page, and the moment I reached his monologues, I was hooked.

And when I’d gone back to my grandmother and told her about my newfound love for Shakespeare, she gifted me the thickest, fattest book I have ever owned. It was my great-grandfather’s collection of Shakespeare’s plays and sonnets. The pages had browned with time and the book had that distinct smell, that only age could give an object. It made me wonder: why would my great-grandfather — a boy from rural 1920s India who worked hard his whole life to become a doctor — be drawn to a playwright from 16th-century Stratford? What could these two men possibly have in common for one’s work to resonate with the other?

That question, about resonance, is not just personal. Beyond the generational and continental bridge between my great-grandfather and Shakespeare, the Bard’s pervasive influence can be seen throughout South Asian cinema. Starting with Vishal Bharadwaj’s trilogy: Maqbool (2003), Omkara (2006), and Haider (2014) which were adapted from Macbeth (1623), Othello (1603), and Hamlet (1623). All of them are set in India, and see these characters navigate the underbellies of the country, from the underworld of Mumbai as seen in Maqbool to Haider’s conflict-ridden Kashmir. They are all deeply Indian but still deeply Shakespearean.

In Shakespeare’s works, props carry the weight of fate. A handkerchief becomes proof of betrayal in Othello; a crown signals both ambition and doom in Macbeth; a skull turns into a symbol on mortality in Hamlet. Bharadwaj understands this grammar of objects. In Omkara, the handkerchief transforms into the kamarbandh, a deeply Indian ornament that holds the same devastating power as its Elizabethan counterpart: a small object capable of destroying a marriage.

These adaptations don’t feel forced; rather, they feel natural and believable, as though the stories were always meant to unfold in those environments, through those characters. The reason is quite simple: Shakespeare’s plays were never just about plot or even about specific individuals. His characters were conduits for universal emotions — jealousy, ambition, hatred, love, anguish.

Many of his stories unfold within the complexities of hierarchy and social reality, and the breeding ground for such tensions has always existed in South Asian cultures. In fact, they form the backbone of our societies and our families. There is an envious uncle, an opportunistic aunt, and a lost prodigal son in almost every desi family — whether we would like to admit it or not.

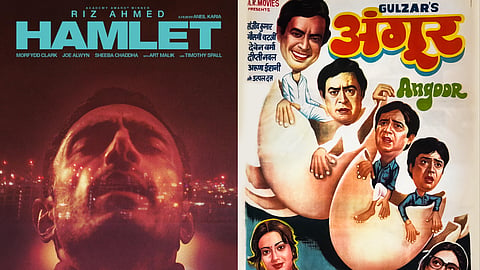

If we go back even further in Indian cinema, Gulzar’s 1982 classic, Angoor, which is an adaptation of Shakespeare’s comedy ‘The Comedy of Errors’. Retaining the original’s premise of separated twins and escalating mistaken identities, Gulzar transplants the chaos into a distinctly middle-class Indian setting. What makes Angoor remarkable is how seamlessly Shakespeare’s Elizabethan confusion slips into Indian domesticity. Suspicion between spouses, anxieties about money, questions of respectability, the constant fear of social embarrassment: all become fertile ground for misunderstanding.

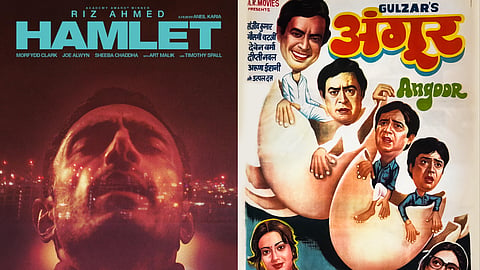

Other Indian adaptations of Shakespeare’s works are Dileesh Pothan’s Joji (Macbeth), Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Goliyon Ki Raasleela Ram-Leela (Romeo Juliet), and Sharat Kataritya's 10ml Love (A Midsummer Night's Dream). Shakespeare’s works are liquid; their beauty lies in their ability to transform, adapt, and mutate into any mould you pour them into. And now, the soon-to-be-released Aneil Karia’s Hamlet, starring Riz Ahmed, Sheeba Chaddha, Avijit Dutt, Art Malik, and more, is a testament to that elasticity.

Set against a contemporary backdrop and led by a cast that straddles cultures, the film promises to re-examine Hamlet through a diasporic lens. If Bharadwaj rooted the Dane in Kashmir’s political unrest, Karia appears poised to situate him within the fractured identities of the modern immigrant South Asian experience. Hamlet has always been about grief that curdles into obsession, about a son suffocated by legacy, about the inertia that comes from seeing too clearly: ‘to be or to be’, that has always remained the question. And those anxieties can always travel across borders.

And that’s also precisely why my great-grandfather gravitated towards his works. And also why I reached for his stories. And yes, it can come off as pretentious to claim Shakespeare as something personal, something intimate, especially in a country that inherited him through colonial classrooms and rigid syllabi.

Nontheless his works hold a timeless mirror against humanity. We study history in the hope of not repeating it, yet human emotion rarely evolves. Perhaps that is what connected my great-grandfather to him. Not an empire or curriculum, but a sense of recognition. The understanding of ambition in a man trying to educate himself against the odds. The ache of generational expectation. The delicate pride of fathers and sons. The moral compromises demanded by society. Shakespeare may have written of gold chests and ships lost at sea, but he was always really writing about inheritance.

Shakespeare’s real genius has never been his ability to endure, but his ability to belong to whoever picks up his book.

Watch the trailer for Aneil Karia's Hamlet here, soon to be released in Indian theatres.