- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

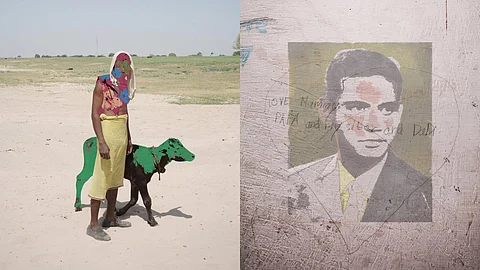

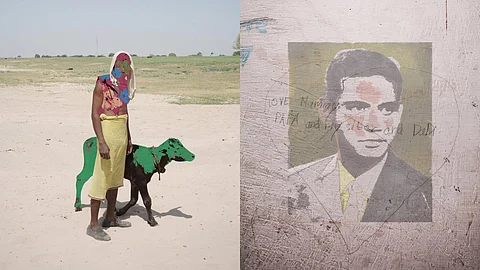

The first civilisations formed and flourished on the fertile banks of rivers. The last civilisations will collapse on barren river valleys. As climate change wreaks havoc across the world, the fading streams of once-mighty rivers tell the story of transformation, decay, and loss. In 'To Lose A River', a four-part photo essay, Goa-based photographer Niharika Chauhan offers a powerful and intimate exploration of this transformation and loss of identity as time enacts itself upon Shahpur, her ancestral village, in Uttar Pradesh.

Through her photographic explorations drawing from environmental observation, memory, and grief, Chauhan portrays Shahpur as a place suspended in time — neither what it once was, nor what it will become. "The most frightening stage in any metamorphosis is when an obsolete form has eroded, but the new one is still a chaotic, pupal mess," she writes, "Shahpur lies on that cusp. Shedding its past it faces a crisis of identity and loss".

At the heart of Chauhan’s project is this profound observation: that the most unsettling moment of transformation is not the moment of arrival, but the space in-between, when the old form has dissolved, and the new one remains unformed. It is in this disquieting, liminal space that Shahpur exists today. Once sustained by riverine agriculture and a thriving ecosystem surrounding the Yamuna which cuts through the village like an artery, Shahpur now grapples with ecological decay, societal fragmentation, and the quiet disappearance of memory.

The photo essay unfolds in four thematically connected parts: In Part I, Chauhan turns her attention to her nineteenth-century ancestral home, now decaying in the absence of its former inhabitants. The home becomes a symbol of rural outmigration and the erosion of once-robust familial structures. "As people leave a house," she writes, "the house also leaves them". In this way, architecture becomes a metaphor for memory, and its collapse, a form of forgetting.

Part II shifts the focus to the vulnerable Sambar deer, once abundant in the forests around Shahpur. Now rare, the animal’s disappearance reflects the environmental cost of unchecked human aggression. Chauhan highlights how the remnants of these creatures live on only in taxidermy specimens — mounted trophies that tell the grim history of caste privilege and human dominance. In this way, the deer becomes a symbol not just of ecological loss, but of inherited violence and social inequality.

"The taxidermied deer head is not just a vestige of human cruelty but a relic of caste-based power. Since hunting was once reserved for the upper castes, an endangered deer became both a coveted trophy and a marker of privilege."

Niharika Chauhan

In Part III, Chauhan turns her lens to the Yamuna River, the arterial lifeblood that once sustained Shahpur. The River's retreat, both literal and metaphorical, highlights the ecological decay that has reshaped the village’s physical and emotional landscape. What future generations will inherit is not the river, but the void it has left behind — with cracked riverbeds and contaminated soil existing as grim evidence of unchecked industrial development and an altered ecology.

At the center of this shifting landscape, Part IV focuses on Chauhan's increasingly hazy memory of her maternal grandfather. His fading presence anchors this project just as he once anchored the family and the social structure that held them in Shahpur. His legacy, marked by both strength and militarism, further complicates Chauhan’s narrative of loss.

A deeply personal project, To Lose A River is as much an elegy to a home that once was and perhaps no longer exists, as it is a cultural and ecological record of a place suspended in time. It is a quiet, haunting act of resistance — against disappearance, against erasure, and in favour of witnessing.

Follow Niharika Chauhan here.