- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

In the long shadow of the Empire, our history textbooks rarely mention the largest drug cartel in modern history, and India’s forced complicity in fuelling it. At its centre was Queen Victoria — lionised as the grandmother of Europe — but beneath the imperial gloss lay a staggering truth: she presided over, and profited from, a brutal, state-sanctioned narcotics operation. The vehicle of this devastation was opium. The engine was colonisation. And the scaffolding of this empire was India.

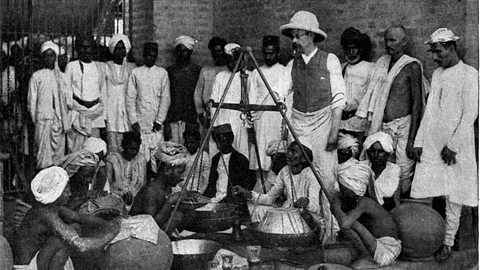

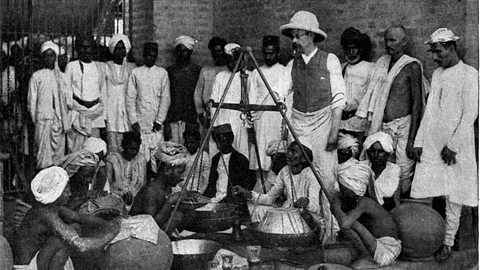

The scale was incomprehensible. By the late 1800s, India was cultivating opium on an industrial scale. Don’t imagine the stereotypical shady smuggler at its helm, but the East India Company, and later the British Crown itself. Roughly 10 million Indians, many in eastern Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, were involved in poppy cultivation. The drug was processed in colonial-run factories in Ghazipur and Patna, where thousands of workers pressed the sticky latex into cakes and packed them into wooden chests marked for China.

The conditions were coercive. Small farmers were forced — by debt, contract, and violence — to grow poppy instead of food. According to historian Rolf Bauer, opium cultivation was a net loss for most peasants. They were paid too little to cover the costs of rent, irrigation, and labour. But refusing to grow it wasn’t an option. Landowners and colonial officers enforced stiff production quotas and the police enforced obedience.

The destination for this opium was China. Britain, gluttonous for Chinese tea but lacking anything the Chinese wanted in return, had found a solution in addiction. The British flooded China with Indian opium. At its height, this trade reversed the flow of silver and reshaped global finance. Queen Victoria’s coffers swelled as the Chinese nation unravelled.

When China resisted, Lin Zexu seized British opium stockpiles and dumped them into the sea, Victoria didn’t negotiate. She sent warships. The First Opium War (1839–42) was Britain’s declaration that free trade meant the freedom to traffic narcotics, and anyone obstructing that would face cannon fire. The result was a humiliating treaty that gave Britain Hong Kong and forced China to open its ports to continued drug imports. The second Opium War (1856–60) deepened this submission.

Victoria, herself, consumed laudanum, a tincture of opium and alcohol, almost daily. She advocated for chloroform in childbirth and cannabis for menstrual cramps. But while her own use was private and medicinal, her government’s export of opium was anything but. By the mid-19th century, 15–20% of British colonial revenue came from Indian opium sales. The Queen’s Empire was built on dope money. No irony was too great: moralists in Britain were beginning to sound the alarm on addiction at home, but across the sea, Britain’s economy ran on the very narcotic it banned within its own borders.

This was not only a British project. Indian capital was entwined in the veins of the trade. Bombay became a financial hub precisely because of opium. The Parsi merchant class, particularly figures like Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy, made immense fortunes facilitating opium exports from the Malwa region to China. Jejeebhoy started off as a Batliwalla (bottle-seller), then a shipping magnate, then a baronet. He gave generously to charities and built hospitals, but the wealth that funded this largesse came from narcotics. The Tatas, too, started off as opium traders but soon realised there was more money to be made in cotton. Opium shaped Bombay’s modernity. It helped finance the early ventures of Indian industrialists. And the city’s glittering skyline today carries, unacknowledged, the hazey scaffolding of that past.

The opium trade entrenched deep regional inequalities. Areas like eastern UP and Bihar, where poppy was forced onto fields, remain among India’s poorest even today. Meanwhile, western India’s early industrial boom — particularly in Bombay — was fuelled by capital accumulated through narcotrafficking. Opium shaped caste, class, and urban development. It allowed native elites to align with colonial rulers. It created philanthropists out of drug barons. The paradox is stark: the same crop that starved peasants in Bihar financed hospitals in Bombay.

Queen Victoria was the greatest drug dealer of all time. Her empire profited off addiction, destabilised Asia, and exploited India. And yet, we’re often taught that this was a 'civilising' mission. There no mentions of the warehouses of poppy, the drowned Chinese bodies, or the ruined Indian villages. Understanding the Indian opium trade through an Indian lens means confronting this hypocrisy. We begin to see that the legacies of empire are in the very social and economic contours of our present.

If you enjoyed reading this, here's more from Homegrown:

The Intersectionality Of Queer Cinema: How Fat Phobia Is Present In The Indian Queer Community

5 Underrated Regional Films That Portray The Everyday Reality Of Queerness In India

How Rituparno Ghosh's Filmography Explored Womanhood Through A Feminist Lens