- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

When we think of climate change, we tend to visualise data: graphs of rising temperatures, satellite images of melting ice, and projections that haunt the future. But long before climate science emerged, ancient Indian artists were painting responses to environmental change. Responses we are only beginning to recognise for their ecological insight. If we look closely, old Indian art registers the tensions and transformations brought about by climatic upheaval. It helps us reframe the climate crisis as a cultural and perceptual one.

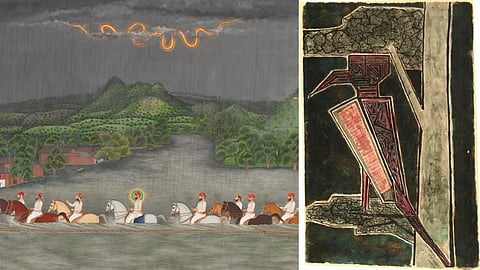

Between the 16th and 19th centuries, India experienced the global climatic phenomenon known as the 'Little Ice Age', marked by erratic monsoons, prolonged droughts, and sudden famines. In the northern pilgrimage region of Braj, where every hill, grove, and river was tied to the stories of Krishna, these disruptions became spiritually significant. Artists, poets, and temple builders responded to the changing rhythms of the land with a theological and aesthetic reframing of nature as divine. What emerged was a form of ecological consciousness.

Water, for instance, became central to this vision. The Yamuna River was reimagined through a “hydroaesthetic” lens. In periods of water scarcity, temple design and painting styles changed to emphasise the act of seeing water. Just looking at the river, artists claimed, could confer spiritual merit. Paintings from this period show Krishna and his companions playing on the riverbanks. The devotional act became intertwined with environmental longing. In these works, beauty was a technology of resilience.

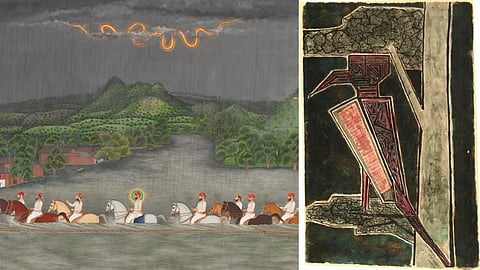

Likewise, the land itself — its stones, hills, and dust — was reinterpreted. Govardhan, a low sandstone ridge in Braj, was Krishna’s body, a living form that bled if wounded. The idea that the earth could feel pain radically challenged the exploitative logic of extraction and cultivation. Temples were built using the same red stone as Govardhan, collapsing distinctions between sacred and profane. In a time of ecological fragility, these constructions served both as shelters and as statements: the land was a being.

Artistic responses to deforestation in 18th-century Braj offer yet another insight. As forests were cleared for agriculture, temple facades and miniature paintings began to bloom with vegetal motifs. Flowers, vines, and groves spilled across walls and manuscripts; art became a botanical memory. While colonial accounts emphasised imperial gardens and taxonomic drawings, Braj’s floral art was a ritualised effort to keep the forest alive in form and feeling.

Crucially, these expressions weren't just nostalgic. They generated new relationships between humans and nature — what art historian Sugata Ray calls 'geoaesthetics'. This approach unmoors our understanding of art from human exceptionalism and instead asks how rivers, rocks, and skies shape, and are shaped by, cultural life. In Braj, ecological instability birthed a vision of the cosmos where divinity and ecology intertwined; where climate change was met not with denial or defeat but with devotional creativity.

Today, as we confront a new age of ecological disruption, old Indian art offers a different framework for seeing and sensing the world. Nature is not separate from us, not to be managed or mourned, but to be honoured, interpreted, and lived with. This doesn’t mean returning to the past or romanticising pre-industrial life. Rather, it invites us to expand our vocabularies of environmental engagement, to acknowledge that scientific models must be met with aesthetic, spiritual, and emotional ones too.

If the climate crisis is as much about how we live and imagine as it is about carbon and temperature, then perhaps old Indian art has always been ahead of its time. It tells us that beauty, belief, and the biosphere are not separate realms. If we can learn to see as those artists once did, we might just find new ways to respond to the storms that lie ahead.

This piece is inspired and informed by 'Monsoon Mood', an episode from the podcast Sidedoor by Smithsonian Magazine. Listen to it here.

If you enjoyed reading this, here's more from Homegrown:

Mukti: A Pathbreaking Indian Video Game Exploring The Grim Reality Of Human Trafficking

Homegrown Game Studios Are Building A Bridge To Authentic Cultural Representation

The Death Of An Artist: How Safdar Hashmi Pioneered Street Theatre As An Act Of Protest