- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

This piece revisits 'Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge' to unpack how its romance, mythmaking, and patriarchal ideals shaped a newly globalising India. Through nostalgia, cultural symbolism, and critique, it examines how the film framed “Indianness” for audiences at home and abroad, revealing both its enduring charm and its troubling limitations.

The year was 1999. It had been about four years since Aditya Chopra's 'Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge' (DDLJ) had been released, and my grandfather had brought home an Alsatian puppy. As the youngest in the family, the responsibility of naming her was given to my mother. And naturally, after years of yearning for her Euro-girl summer and dreaming of bumping into her own Shah Rukh Khan, she named the puppy Simi — short for Simran, after Kajol’s character in DDLJ.

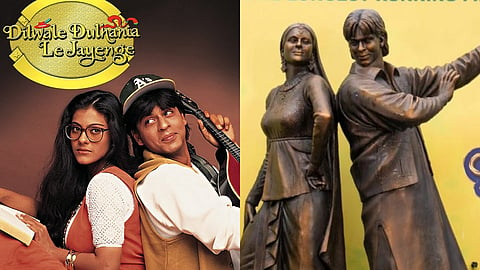

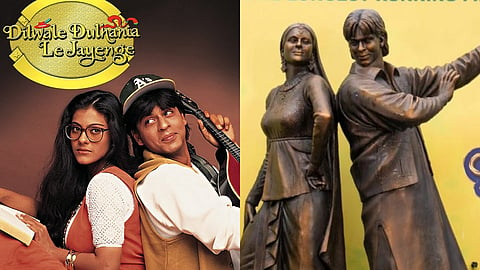

Now everyone who is even somewhat acquainted with Bollywood and Indian culture knows what DDLJ is. From the rolling green hills of Switzerland to the 'sarson ke khet' (mustard fields) of Punjab, the star-crossed story of a bratty NRI boy, Raj (SRK), and a rule-abiding NRI girl, Simran (Kajol), unfolds as an unexpected romance born during a chaotic European trip. The film’s charm, scale, and emotional sweep broadened what the average Indian could dream of in the mid-90s. Nearly 30 years after its release, that influence has come full circle, now immortalised in Leicester Square with a bronze statue of the iconic pair.

In 1991, the Indian government introduced revolutionary economic reforms collectively called LPG — Liberalisation, Privatisation, and Globalisation. As international brands entered India and the middle class grew, the country was undergoing a shift in aspiration and identity. DDLJ arrived at precisely this moment of transformation. It was a film that captured this new sensibility, reflected a more global Indian gaze, and reshaped how the world viewed Indian cinema. Instead of merely claiming the Indian imagination, it became a marker of a nation newly stepping onto the global stage.

When DDLJ came out, it was a resounding hit, collecting ₹800 million in its first month of release. Aditya Chopra’s debut as a director is not without its flaws. The film operates through an unmistakably patriarchal lens: Simran has virtually no autonomy over the events of her life, and her need for validation or permission from the men around her is both jarring and undeniable. Even Raj’s misguided attempts to 'seduce' her veer into the problematic and, at times, the borderline perverse.

This patriarchal framing ties directly into how the film constructs India itself. DDLJ portrays the country as the 'homeland' — the fulcrum of authentic values and idealised culture. Even though Simran’s family has long settled in London, they remain committed to preserving their 'Indianness'. In the context of the 90s, this meant dreaming big and seeking prosperity abroad while staying emotionally tethered to the place they came from — which, means obeying one’s father, marrying the man he chooses, and accepting tradition without doubt or question.

In her review of the film, Anupama Chopra for NDTV wrote: “Perhaps it’s the innocence of Raj and Simran’s romance, in which they can spend the night together without sex because Raj, the bratty NRI, understands the importance of an Indian woman’s honour. Perhaps it’s the way the film artfully reaffirms the patriarchal status quo and works for all constituencies — the NRI and the local viewer.” This is true — the film opened the floodgates for a wave of diaspora-focused Bollywood cinema that followed. Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham (2001), Kal Ho Naa Ho (2003), and Kabhi Alvida Naa Kehna (2006) — all made by Karan Johar, who had worked as an assistant director on DDLJ — carried forward this blend of global aspiration, family values, and NRI identity that DDLJ helped define.

The film is undoubtedly a classic and has created a template for love and love stories for years to come. Perhaps if it were released now, in the current cultural climate, it might not play as well. Raj would likely be called a manchild, and Simran might be labeled voiceless. But the movie works in remembrance — of a time when India was young and restless; trying to navigate its growing pains and figuring out how to hold on to its origins while also striving to grow. And, much like its own climax, the country eventually learned that there is little value in clinging to who it thinks it should be, and far more freedom in allowing itself to evolve — just as Simran, in her wedding ensemble, finally breaks into a run toward a blood-soaked Raj who has fought for her love.

If you enjoyed reading this here's more from Homegrown:

The Film That Lived Forever – Watching Shah Rukh Khan's DDLJ At Maratha Mandir

For South Asian Women, Inheritance Becomes A Solemn Form Of Resistance

Conan O’Brien & The Double Standards Of Tourism For The Global South