- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

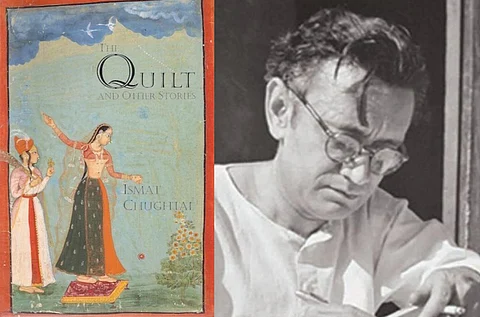

One of the most controversial Urdu writers of the twentieth century, Saadat Hasan Manto, faced censorship throughout his literary career and somehow this legacy even followed him in his death. The arthouse film ‘Manto’ directed by Nandita Das faced much scrutiny from the board and was eventually banned in Pakistan. The film was cited as ‘anti-partition’ and inflammatory towards religious groups all due to its real depiction of the horrific events.

It is interesting to look back and analyse what truly made the public so angry with an honest portrayal of society? Manto’s stories usually found a setting in Mumbai and focused upon themes of violence and sexuality in the more customary sense. Ahead of his time, Manto reflected on the hypocrisy existing within society, especially towards women. As he was brave enough to point out the acts of violence committed on women in the name of communal honour and national pride.

Many labelled him as crude or vulgar since his stories openly spoke of women’s sexuality. Although he was arrested for obscenity, his accounts showcased women with agency who held their own individualistic ground and explored the realms of desire. Beyond these, Sarah Waheed explains that his stories allowed readers to see the world through the eyes of prostitutes, pimps, gamblers and rickshaw drivers negotiating the painful spaces between ghar and ghat.

His short stories were banned three times before Partition in colonial India and thrice afterwards in Pakistan. Accusations were hurled at him in society as well as in courts. There are also no copies of the stories available in the Urdu collections of university libraries as they were banned by authorities on the grounds of having a “corrupting influence on youth”.

Manto was not alone in his escapades with the judiciary, his contemporary Ismat Chughtai was also brought before a judge on charges of obscenity for the short story 'Lihaaf'. The same-sex politics in Lihaaf broke the silence about the sexual needs of a woman by openly exploring their desires and aspirations. Caught in the entanglement of law, nationalism, and gender in British India, the young writer rebelled against the state and stood up for the freedom of speech.

In her paper ‘Flak and Censor: Ismat Chughtai’s ‘Lihaaf’, The Story on Trial’, Shaifta Ayub notes, Ismat had no idea that it was sinful to write on the subject with which ‘Lihaaf’ is concerned. She maintained that if any prevalent tendencies existed in the society she was well within her rights to write about them. Chughtai’s woman was a complete woman; searching for an opportunity to break out and lead her life on her own terms. Which made her texts even more threatening to the sanctity of a misogynistic society.

In present times, instances of literary censorship are ample. Many books are banned on grounds of hurt sentiments, obscenity or threat to national security. Famous book, 'The Hindus: An Alternative History' had offered genuine critique of right-wing groups but was banned around the country on the account of being insulting to religious deities. India was also the first country to ban the infamous book The Satanic Verses written by Salman Rushdie on the account of hurting religious sentiments.

With the prevalence of social media as a primary means of communication, censorship can also be seen in the form of infringement on speech on many platforms. Recently, many raised concerns about the censorship of Palestinian experiences on social media.

In the times of polarised opinions, censorship can only do more harm as violation policies can be used to flag the real voices of dissent that might be far-fetched. Our present day limited societal outlooks are a result of the curtailed speech in Manto and Ismat Chughtai’s time. Their opinions greatly differed from the masses yet were worthy of being freely circulated. We must be aware that our words in literature or on social media can influence real change and hence safeguarding them from censorship is a huge step towards true freedom of speech.