- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

In September 1965, as fighting broke out on the India–Pakistan border, a series of songs began circulating on Radio Pakistan that cut through the fear and fatigue of war. Sung in a voice that was at once commanding and tender, they reached soldiers at the front lines and families gathered around radios at home. These recordings, 'Aye Puttar Hattan Te Nahi Wikde' and 'Aye Watan ke Sajeelay Jawano' among them, became anthems of resilience. The figure behind them was Noor Jehan, a singer whose name was already synonymous with cinema and music across the subcontinent.

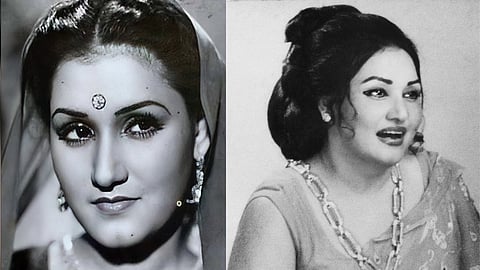

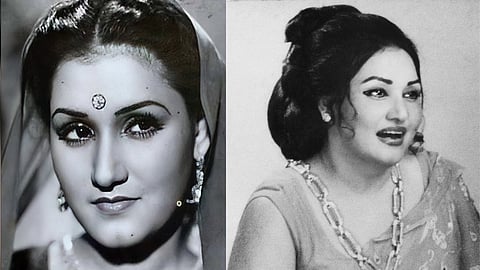

Born Allah Rakhi Wasai in Kasur in 1926, the artist the world would know as Noor Jehan began as 'Baby Noor Jehan', a prodigiously gifted child performer on stage and in the Punjabi film industry before adolescence. Her early roles in 'Heer-Sayyal' (1937) and 'Gul-e-Bakawali' (1939) showed a singer already grounded in classical training, with a voice that quickly drew the attention of composers and directors who began creating work with her timbre in mind.

In her later years, Noor Jehan brought ghazals and traditional poetry into popular consciousness by infusing them with her singular expressive elegance. Her renditions of Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s 'Mujh Se Pehli Si Muhabbat' and 'Aa Ke Wabasta Hain' became touchstones of ghazal interpretation, while her recordings of Ahmad Faraz and other poets expanded the audience for contemporary verse. She melded the weight of poetry with a melodic sensibility that made such works accessible without diminishing their depth, elevating ghazals from niche refinement to mainstream emotional resonance.

The break that cemented her in public memory came with 'Khandaan' (1942) and, soon after, a run of Bombay hits: 'Zeenat' (1945) and 'Anmol Ghadi' (1946). In 'Zeenat' she led a women’s qawwali, often cited as a first in South Asian cinema, showing how comfortably she could carry classical phrasing into a popular form. 'Anmol Ghadi' made her an indisputable star — the songs were built around her voice, not the other way round.

Partition redrew borders and careers. Noor Jehan moved to the new Pakistan, co-founding Shahnoor Studios in Lahore with director Shaukat Hussain Rizvi. In 1951, she did something unprecedented: she directed 'Chann Wey', becoming Pakistan’s first female film director, while also acting and singing for it. It performed robustly at the box office and remains a landmark of early Pakistani cinema. After a string of leading roles, she turned decisively toward playback singing — an arena in which her command of raag, diction across Urdu and Punjabi, and astonishing dynamic control made her an institution.

Noor Jehan's phrases were sculpted to land exactly on the emotional contour of each line and her trademark glide from chest to head voice was gave her songs that much more meaning. Even at soft volumes, her tone stayed centred. In the studio, colleagues recalled how she would rehearse a single murki until it sat naturally in the sentence. It was never an ornament for its own sake. That discipline explains how she could move from thumri-inflected film songs to ghazal and folk idioms without pastiche.

During the war, she recorded patriotic songs for Radio Pakistan that listeners felt in their bones. Popular accounts recall her arriving with poet Sufi Tabassum’s lyrics, writing melodies on the spot and cutting live takes that crackled with urgency. The broadcasts turned her into a national voice that transcended cinema and her anthems from that period still endure.

The numbers attached to Noor Jehan are large — thousands of songs over six decades; state honours including the Pride of Performance and the Sitara-e-Imtiaz, but the statistics obscure the real measure of her achievement which was her voice. Her recordings show how a singer can be both technically exacting and unmistakably human. Across the border, admiration was frank. Naushad spoke of her in superlatives, and press accounts also note a warm friendship with Lata Mangeshkar. The musical traffic between Bombay and Lahore remained porous in that way, despite everything.

By the 1970s and 1980s, she had affectionately come to be known across the subcontinent as 'Madam Noor Jehan'. She was titled as 'Malika-e-Tarannum' (Queen of Melody) for the unmatched authority of her voice, and The 'Voice of the Century' as declared by Pakistani television. She was also called the 'Nightingale of the East', the 'Queen of Hearts', and even the 'Daughter of the Nation' — each name capturing a different facet of her presence, from her artistry to the deep cultural imprint she left behind.

Her public identity was inseparable from her music: it was a symbol of sophistication, command, and artistic authority. She represented a rare synthesis of glamour and technical mastery. For younger singers, she became the gold standard; someone to emulate and measure themselves against. Her presence on radio and television, as much as in cinema, made her a household name whose voice was woven into everyday life.

Noor Jehan died in Karachi on December 23, 2000, after cardiac complications, and was laid to rest at Gizri Graveyard. The grief was immediate and public, befitting someone whose songs had threaded through millions of private lives.

Pakistani poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz once said that his poem 'Mujh Se Pehli Si Mohabbat' no longer belonged to him but to her, speaking to how fully she could inhabit and transform another’s work.

Even today, Noor Jehan’s songs continue to be rediscovered by new generations and played at weddings, revisited on streaming platforms, and reinterpreted by contemporary artists. Her music shaped collective memory, attaching itself to moments of war, migration, and everyday longing

Beyond music history, her career created a template for women across the region: one of an artist whose authority on stage, in studio, and behind the camera underlined that creative leadership isn’t contingent on gender.