- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

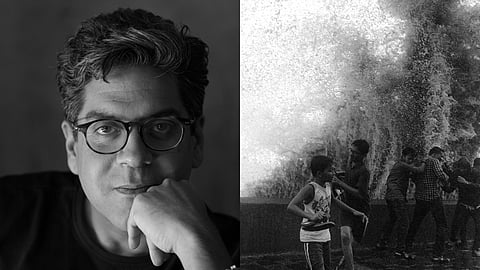

In 2012, Mumbai-based photographer and filmmaker Sunhil Sippy was at work when a serious accident led to the loss and subsequent reconstruction of his left heel. The injury that could have incapacitated him became a turning point in his life and career. Ironically, his healing involved walking, and walking precipitated his journey into street photography. He picked up a camera and photographed the streets of Mumbai — a city hidden in plain sight, one he had known for years but never quite understood.

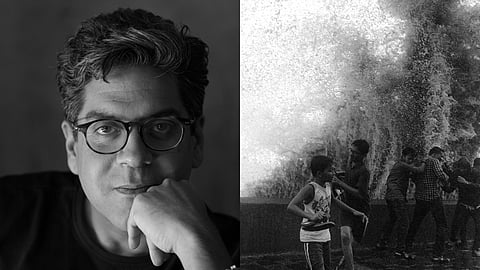

‘The Opium of Time’ (Pictor, 2022), his first monograph — a collection of over 100 monochrome and colour images and diary entries made by him over a decade between 2010 and 2020 — was the result of these meditative urban explorations. With a foreword by filmmaker Zoya Akhtar and poems by singer-songwriter-music director Ankur Tewari, ‘The Opium of Time’ is a book-length visual love letter to Mumbai — an unvarnished, gritty, but also somehow romantic, though not necessarily romanticised celebration of the city which has been an integral character in his photographic journey. Born and raised in London, UK, and educated in the USA, Sippy moved to Mumbai in 1995 to pursue a career in film and advertising. He was in his mid-20s at the time.

Today, he is one of the most important photographers working in India. His photographs of Mumbai capture the wistful nostalgia of memories without wallowing in sentimentality about the city. Incredibly moody, cinematic, and evocative, his images — made primarily on black-and-white film — capture the hidden and not-so-hidden pockets of Mumbai that exist in the liminal space between the city’s urban mythology and its reality… its many faces, moods, and seasons, especially its fabled monsoon.

Although his personal work accounts for almost the entirety of his photographic output, he has recently taken up interesting commissioned assignments — working as photographic archivist to the virtuosic designer Sabyasachi Mukherjee (Sippy shot the Kolkata-based designer’s 25 Years of Sabyasachi campaign recently); collaborating with historical city-chronicler Simin Patel (Miss Bombaywallah); and supporting the Film Heritage Foundation with their photographic archive.

Recently, I spoke to Mr Sippy about his photographic practice. Taking place over emails and an almost hour-long conversation over Google Meet, the subjects of our correspondence ranged from his approach to photography and the curatorial process behind The Opium of Time, his current and ongoing project Race Day, to his thoughts about smartphone photography and contemporary visual culture.

You grew up in London, studied in Washington D.C., and now you live and work primarily in Mumbai. London and Mumbai, alongside New York and Paris, are perhaps two of the greatest cities for street photography in the world. How did your time in London and Mumbai influence your photographic practice?

In London, I grew up in an idyllic suburban neighbourhood, and was quite sheltered in many ways. My curiosity levels were low, and I kind of lived in a bubble. When I moved to Bombay in 1995, even though my work took me to many different parts of the city, I remained blinkered, so to speak — "blind" to so much that the city was offering.

As my career as a director evolved I found myself spending more and more time inside film studios, often shooting beauty commercials. While the work was challenging and prestigious I began to feel claustrophobic. It was around 2008 that my journey onto the streets began but it was only after a serious accident at work in 2012 that my practice became more serious.

While I had no real purpose through these explorations, (remember there was no social media at the time and so nobody to share these experiences with) in retrospect I see that I was just trying to understand my context in the city. When asked about the purpose of my work I often respond with the simple phrase “to understand where I am”. It sounds terribly banal, but many of us can carry on with our lives without any understanding of our whereabouts, not that it's critical to living a thoughtful existence, however for me, once I began to understand my geography through these explorations, so much more about the city made sense to me. This sense of curiosity now guides me in life, wherever I am in the world.

You are both a filmmaker and photographer — making scripted films in controlled environments, and spontaneous, unplanned, and often uncontrollable, “decisive moments” on the streets of Mumbai. How is Sunhil Sippy the filmmaker different from Sunhil Sippy the photographer?

The filmmaker in me has always been frustrated by the structure of the industry. Immense creative control is wielded by producers, networks and agencies, and navigating this universe was very challenging for me. While I was "successful", I was only really good at delivering on the needs of others, and to do so I had to sacrifice my own voice. When I hit the street I felt free, agile, and able to express my individuality and vision.

As a filmmaker, I saw myself more as a visual artist than a director. I was able to construct beautiful frames and express clear narratives succinctly as was the need in the world of the 30-second commercial. However, I failed as a long-form storyteller in that medium. Mike Leigh, one of my favourite directors, never writes a script. He rehearses with actors and builds a narrative over time and then executes the film. He takes his time to find the language and structure of his cinematic narratives. He has, however, earned the right to work this way. I resonated with his process but found that I was only able to work this way photographically and not cinematically.

On the street, the photographer in me could truly dance freely — I could embrace uncertainty, celebrate mistakes, seek patterns and unwittingly embark on long-term journeys. I felt I had begun to flourish. All roads lead somewhere, and my journey through filmmaking was invaluable. But I’m profoundly grateful to have found something that I truly love, where I can express myself as freely as I can now.

Your first monograph ‘The Opium of Time’ is a photographic portrait of Mumbai and its many faces, moods, and seasons, especially the legendary Mumbai monsoon. The book consists of a body of work 10 years in the making, and I think you once mentioned during an interview that it took 2-3 years to curate. I’d love to know about your curatorial process and how you choose which images to include from what I imagine must be a massive archive.

When it came to the curatorial process, it was as aimless as my photographic practice often is. I refer to something I call an “archive trudge”, which involves deep dives into my negatives and hard drives. This process mirrors my experience of walking the streets with no particular destination in mind. Inadvertently, I had never labelled my folders, simply archiving my work month by month, year by year, without descriptions of where or what I had photographed.

This meant that when I needed to find something, I had to rely on memory. Often the way I’d make a left or right turn searching for a place I had once visited, and then stumbling upon somewhere even more magical — I was similarly wandering through my hard drives and negatives searching for images. And often, I’d stumble upon photos I hadn’t really paid any attention to earlier. This process unfolded in stages. First, I had to tame this amorphous beast that was my archive, and then, I worked to organize the images into a loose narrative. I tend to use Instagram like a sort of personal journal and many of my entries became the basis for much of the text in the book, and it was this carefully structured text which anchored the images.

The book had a print run of 1,000 copies and is now almost sold out (almost solely from the link on my Instagram bio) and seems to have connected well with its audience. As I prepare for a second edition, it’s fascinating to see how little I plan to change. In hindsight, the precision of the curation is evident, even though it felt somewhat arbitrary at the time.

You’ve previously spoken about how you used to work with only one focal length when you first started making images — preferring to move with your feet to compose images. You’ve worked with a plethora of focal lengths and formats since then. If I’m not mistaken, you prefer to work with Medium Format 120 - 6”x6” film now. Do you still have a specific focal length that you naturally gravitate towards and like to work with?

I essentially work with a 35 mm focal length on a rangefinder system — it’s my go-to lens. On the Hasselblad (medium format film), I use a 55 mm lens. This is the way I’m best able to interpret the world that I see as an image-maker. Many people struggle with the square format — I love it, especially the way the language of the 120 format contrasts with my work in 35 mm. However, in the last few years, I’ve allowed myself to play around a bit more. But I’ve noticed that my voice changes when I experiment too much and then I lose my way. And so I often return to my tried and tested practice, but perhaps with a freshness and vitality.

You’re currently working on your second book titled ‘Race Day’, about Mumbai’s iconic racecourse and all its trappings. What drew you initially to the racecourse as a subject?

I’ve always lived close to the racecourse and often taken it for granted as a beautiful open space in the city. Historically, my paternal grandfather owned racehorses in the 60s and 70s; he was a gambling man. However, that never fueled any personal interest in racing for me. As with most things in my practice, I stumbled upon this subject rather serendipitously. It was after sharing some images of horses riding one misty morning with two senior racing trainers at a dinner party that I gained access to this world.

Once inside, I was fascinated. Initially, I recorded it for myself, with no clear intention or purpose. It was only four or five years later that I noticed an interesting body of work coming together, particularly as its surroundings started to change dramatically. While the urban landscape was changing so dramatically, the world inside remained static, timeless perhaps — the jockey rooms, the gambling areas — these spaces seemed frozen in time, contrasting sharply with the swiftly transforming city outside.

I found this very interesting and worth exploring more deeply. This juxtaposition captivated me. I began documenting the outer world’s changing landscape while viewing the inner world of racing as a place of continuity. In a city undergoing tremendous flux, I found solace in these pockets that clung to old values and systems of living.

You have been making images for close to 12 years now, and films for twice as long. How has the proliferation of smartphones — often the most accessible camera and sometimes the only camera many of us have — changed the language of photography and visual culture over the years? Do you see any discernible changes in how people make and interact with photographs now?

I'm probably one of the few people in the current photographic environment who remains thoroughly uninterested in the smartphone photography culture. While it’s fascinating and incredible that such varied imagery can be made with a smartphone, I don’t really see it as particularly interesting. There's a distinct difference between making an image and taking an image. Making an image involves a series of deliberate choices — choosing the focal length, the aperture, and the film type — responding to one's environment with both alacrity and mindfulness. For example, in the past, you would load black-and-white film or a particular ISO based on the environment and your creative intent, decisions made before capturing the image, not after.

Yes, there’s a proliferation of imagery today because of the smartphone, but the real question is — how much of it endures? It’s not about the sheer number of images being made but about which images linger and resonate. If one is to be fair, the medium through which an image is made — whether on a phone or a camera — matters less than the thought and intent behind it. However, the ease of making images with a phone often leads to a flood of pictures, lacking the consideration that goes into the act of making an image with a ‘camera’.

When shooting medium format film, I have just 12 exposures on a roll. I must carefully consider each one, and the selection process is easier in a sense since there are fewer options. In many ways, I’m editing while I'm composing the frame. In contrast, when shooting digitally, I might return with 300 or 400 images from a shoot, which is frustrating and tiring to sift through. If the same principles of restraint and curation applied to smartphone photography, it might be more legitimate. However, phones were originally designed for talking to one another, not for creating pictures. That’s why they’re called phones. What made them ‘smart’ seems to have blurred that original intent.

As a writer who also makes images, I have been following your work since I started learning photography during the lockdown. So this is a question I have been meaning to ask you personally since then. If you could give all photographers who are just starting out one piece of advice, what would it be?

Starting out in photography is both exciting and challenging. There’s often this looming question: “How will I make a mark?” But that mindset is the problem. Photography should ideally be embraced as an art form in and of itself, not a race for recognition. Focus on the process, respect your feelings, and use photography as a meditative tool to discover who you are. It’s not about finding an audience or seeking validation through social media likes. Your spirit should guide your work.

And the journey should be slow. In my early days, I fell into the trap of wanting recognition, but over time, I let go of those desires and focused on the solace photography provided me. Whenever I felt low, photographing helped settle my spirit. I now see it as a spiritual practice, and many rewards have come without seeking them.

Over time I discovered a truth that guides me without fail — certainty can be your greatest enemy while doubt can be your finest friend. The moments when you feel lost are often where your best work emerges. Patience is vital for young photographers. It takes time to tune into your own voice and understand your spirit. It may take years, but that understanding is essential for creating honest, meaningful work.

If you enjoyed reading this, here's more from Homegrown:

Keerthana Kunnath's Portraits of Female Bodybuilders Redefine Notions Of Femininity

Rain Dogs: How Goa's Strays Helped A Photographer Weather The Desolation Of The Pandemic

Imdad Barbhuyan's New Photoseries Is An Exploration Of Grief, Fragility, And Resilience