- HOMEGROWN WORLD

- #HGCREATORS

- #HGEXPLORE

- #HGVOICES

- #HGSHOP

- CAREERS

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT US

In the late 16th century, when the first Portuguese Jesuit missionaries arrived at the court of Mughal emperor Akbar, one of the many gifts they presented to the emperor was an illustrated Bible published by Christopher Plantyn in Antwerp between 1568 and 1572. Apparently, the emperor was so moved by the Plantyn Bible's imagery that he knelt down to venerate a picture of Christ and the Madonna. The moment marked one of the most remarkable cultural exchanges in the history of Indo-European relations.

The Jesuits also brought many European prints, engravings, and paintings to Mughal India. These religious prints and paintings of Biblical imagery were greatly valued by the Mughal elite, newly converted Indian Christians, and miniature painters employed by Indian royalty.

The Jesuit Missions And Mughal Miniaturists

What made the exchange between the Mughals and the Jesuits different from the other missionary encounters of the period was that both parties had reached a comparable stage of intellectual florescence at the time and were willing to learn from one another. True Christian humanists, the Jesuits, introduced the Mughal court to a wide range of Renaissance art and culture through their early missions in Fatehpur Sikri, Agra, and Lahore, and learnt from Mughal India's own renaissance in creativity, experimentation, and tolerance beginning in the 1580s.

Many Mughal painters responded immediately and positively to the engravings and paintings brought to India by the early Jesuit missions, but four of them — Kesu Das, Manohar, Basawan, and Kesu Khurd — became specialists in European-style paintings. Mughal painters were especially fascinated with the power of these images and their ability to depict the spiritual, embody abstract ideas, stimulate devotion, and aid the memory. By the turn of the century, paintings and drawings in which Christian devotional images were the primary subject represented a significant part of the Mughal court's creative output.

Christian Imagery In Indian Modern Art

Even in the modern era, the humanist ideas at the heart of Christianity continued to influence modern Indian masters like M.F. Husain, F.N. Souza, Jamini Roy, and contemporary artists like Akbar Padamsee, Krishen Khanna, Madhvi Parekh, Anjolie Ela Menon, and others.

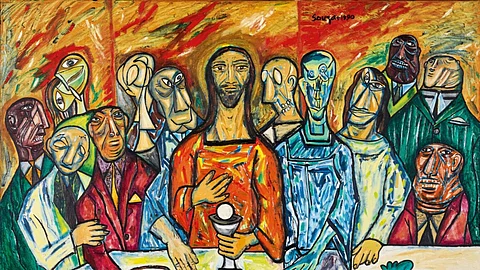

'The Last Supper' (seen above) offers us a glimpse into M.F. Husain’s sense of humanity and moral values. The large 72-inch x 90-inch oil painting depicts Christ sitting at a table with an open book in front of him. His torso is shaped in the form of a dove. The table, roughly cut, is lifted by the devil at one end and by an angel at the other. A woman, garbed in a robe that covers her head, cups a candle in her palms. She is seen standing by Christ, on his left-hand side; on his right is an elderly bearded man and an imposing frame of a dark woman. The fulcrum of this entire scene is an empty bowl at the centre of the table. "The empty bowl signifies betrayal," Husain had supposedly commented at one point.

Husain was witness to a tumultuous period in human history when humanist values were in rapid decline across the world, and his late works mirrored the sense of betrayal, loss, and anguish the exiled artist felt. A colourful yet profound interpretation of an iconic Biblical scene, The Last Supper, painted in 2005 in London, is one of the most powerful paintings in his pivotal series, The Lost Continent.

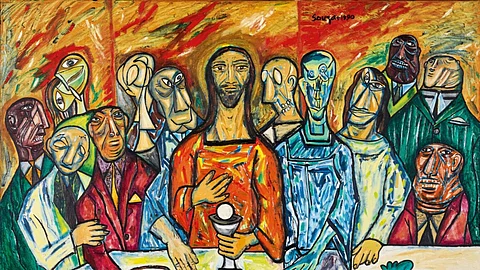

A subject favoured by artists throughout history and made famous by Leonardo da Vinci’s 15th-century fresco at the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, Italy, the Last Supper also greatly influenced the works of F.N. Souza. Souza depicted the aftermath of the last supper in some of his most celebrated masterpieces, such as Crucifixion (1959), where Christ is represented in agonizing pain upon the cross; and Deposition (1963), where Christ’s crucified, bleeding body is moved for burial.

A few decades later, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Souza painted several versions of the Last Supper in his signature style that combined Eastern and Western styles and motifs. In 'The Last Supper' (seen above), the faces of Jesus’s Apostles, with their high-set eyes, lopsided features and harsh outlines, evoke the artist’s stylised heads from the late 1950s and 60s. However, Christ himself does not suffer the same facial distortion, except for his elongated neck and enlarged features. Souza furnishes Christ with a dignity not as clear in his subversive depictions of the Apostles.

From the mid-1970s onwards, carefully chosen scenes from the life of Christ — like the last supper and its aftermath — began to appear in Souza's canvases more frequently. According to author Maria Aurora Couto, "He returned obsessively to make his Christ symbolic of suffering and mankind, dehumanised, vile and ugly, pitiable, surrounded by implacable fate."

These Indian artists did not see Christ as the son of God, reformer, healer, preacher, iconoclast, or leader of men. Instead, in their imagination he became the human ideal pushed to the brink by betrayal and greed. The religious, Biblical context became overwhelmingly social, and the Christian mythology became a subaltern, Indian tragedy — an outcome of conflict with figures of authority, dominant social norms and customs, and apathy in the face of human suffering.

If you enjoyed reading this, here's more from Homegrown:

A Confluence Of Cultures: The Unique Christmas Traditions Of The Syro-Malabar Christians

Reimagining The Life Of Jesus Christ In The Asian Context Using Art